April 22, 1991

Case: Ivan Rocha

|

Where is Ivan Rocha?:

April 1, 2003

Center for the Defense of Human Rights in the Extreme South of Bahia.

Where is Ivan Rocha? That has been the unanswered question for the past 12 years, there being no indication of any interest in answering it.

Ivan Rocha disappeared on April 22, 1991, in the city of Teixeira de Freitas, at the southern tip of Bahia state, after having promised in his program “A voz de Ivan Rocha” (The Voice of Ivan Rocha), broadcast by radio station Radio Alvorada AM, to hand over to Judge Mário Albiani, who planned to visit the city the following day, a file on organized crime containing the names of police officers and an influential local legislator involved in a death squad in southern Bahia. In the city, which has a population of some 108,000 and is located 518 miles south of the state capital of Salvador, Rocha is the symbol of an ever-present past that every once in a while reappears in the voice of human rights advocates in their battle to put an end to impunity.

Despite resistance put up by district attorneys working in Teixeira de Freitas, the IAPA was able to come up with new information that indicates that the case could be reopened. Police detective Jackson Silva, who led the investigation at the time and now is the police chief in Ubatã, told the IAPA, “certainly, the people who committed the crime are those who were arrested and later acquitted and probably burned the body, which has yet to be found.” The police officer’s declaration was based on one fact – after the accused were set free in mid-1994, Silva was on duty in Porto Seguro when he met one of them, who told him that “they are never going to find the body, because we set fire to it.” Silva told the IAPA that he did not take up the case again because he no longer worked in southern Bahia and District Attorney Edward Cabral Costa, in charge of his legal process, had retired. He said he had been subjected to a lot of pressure during his investigation.

From the outset the inquiries were hampered by a series of pressures not to continue. But in May 1991, Brazilian Attorney General Aristides Junqueira accepted a writ filed by the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj) accusing Governor Antônio Carlos Magalhães of “crime by omission” for failing to follow up the Rocha case.

In July 1991, Silva submitted the report on his investigation, which described Rocha’s disappearance as a kidnapping and naming as suspects Salvador Rodrigues Brandão Filho, who worked at a radio station owned by Congressman Temóteo Alves de Brito, and military police officers Antônio Carlos Ribeiro de Souza, Domingos Cardoso dos Santos, Adilson Dias Ramos and Joel Caetano Pereira. The Stater Attorney’s Office felt there was only evidence pointing to the participation of Souza, Brandão Filho and Santos. The latter was acquitted, while the other two were sentenced to five years’ imprisonment, but the Bahia court later upheld their appeal and they, too, were acquitted. The defense was that the journalist’s body had never been found, and the case was suspended in 1994.

Other shortcomings that emerged in the investigation contributed to its suspension. The chief witness, Cirlene Alves Neto, was abducted and then released in August 1991. She later changed her testimony concerning the accused. According to Rocha’s mother, Valdelira de Jesus, Alves Neto’s adbuctor was the same person who kidnapped her – a former police officer known as Cidadão (Citizen), who took her to a local televison station in Salvador to force her to accuse her son of false representation, because he had adopted the name of his cousin, Ivan Rocha – his real name being Valdeci de Jesus.

Residents of Teixeira de Freitas say that Alves Neto lives with the police officer who abducted her.

The IAPA talked to family members of Alves Neto in 2002 and although scared they reported that she was living in another state. They also told how Alves Neto had described Rocha’s abduction to them and had later gone to live with another police officer, known as Cidadão, with whom she had a child, and her stormy relationship was with him, ruled by fear.

All these facts would be sufficient for the case to be reopened and the guilty brought to justice. But what occurred was a series of irregularities that helped maintain the impunity. Contrary to what had happened in the case of journalist Tim Lopes of TV Globo – who disappeared on June 2, 2002 (and later was found dead), raising a national hue and cry, with the police hunting down those responsible and identifying the body – in Rocha’s case doubts fueled by rumors remain.

For a long time two opposing political groups predominated in the area – the Brito oligarchy (linked to Temóteo Alves de Brito) and the Pinto oligarchy (linked to José Ubaldino Alves Pinto, Uldoprico Pinto and Francistônio Pinto). Radio Alvorada AM was owned by the Pinto group. “What people say is that the adversaries gave money to Rocha to travel to the United States and that they attempted to implicate me in the case,” said Temóteo Alves de Brito, who was twice elected mayor – one time after Rocha’s disappearance when he was a congressman and resigned his post to run for mayor.

“What people say is that they took Rocha to another country,” agreed Pedro Silvério Moreira Braga, who hosted a music program at the same radio station as Rocha and who worked as an adviser to the candidate backed by Temóteo Alves de Brito in the state gubernatorial elections in 2002.

Braga went on to become a public enemy of Rocha after striking him in the street – Rocha had written in his newspaper that Braga was being sued for allegedly seducing a young woman. “We became friends again and I was acquitted, he apologized and so did I,” Braga said. “Rocha was very fond of the truth, but he was sensationalist in the newspaper,” he added. In 2002, the two rival groups got together in a joint political program, which put solving the Rocha case even more on a back burner.

As in the Tim Lopes case, which occurred in Rio de Janeiro, in Teixeira de Freitas bones and clothing were found, but that evidence in southern Bahia disappeared. There was no money to have the bones DNA-tested, which could have proved Rocha’s death. With no body, no remains and no evidence the suspects who had been charged were released from custody and the case was suspended.

District Attorney Edward Cabral Costa, now retired, said that he was no longer on the case at the time it was suspended and h does not understand why it did not proceed. “The young man was kidnapped, a person (Cirlene Alves Neto) saw and described in minute detail for two hours before a judge how the kidnapping occurred,” he said. But he recalled the problems that arose in the process. “There were so many telephoned death threats that I was forced to send my son to Salvador,” he said.

The pressure came from all sides. “At the State Attorney’s Office they demanded that I give them confidential details, but when I saw that what was up was politicking, I went to public prosecutor and told him it was not my intention to please Governor Antônio Carlos Magalhães,” said Costa, who withdrew from the case after naming those allegedly implicated. “We never got to the mastermind, but we did get to the perpetrators,” he declared.

Auxiliary Judge Benedito Alves Coelho was the one who pronounced sentence, because the regular judge, Kátia Suely Dantas Carilo, had 5,000 cases pending. Coelho has not doubt about the guilt of the accused. “I judged, I convicted, I had extensive evidence before me,” he said. “But there were pressures, attempts to direct the proceedings and scare me, I had some very bad times,” he recalled.

He added that he asked for Civil Police protection, because the military police had denied him it. “In fact, it was not only an abduction that happened to the radio announcer, but because there was no body I had to convict on the charge of kidnapping,” Coelho said. He added that he was surprised to learn about how the case ended up. “Does that mean that the court amended my sentence? The court was very politicized at that time,” he commented.

Gilberto Ribeiro de Campos, Teixeira de Freitas district attorney since 1996, reopened the case in order to make a report. “That process went through all the possible legal procedures, but in the Bahia court Judge Ivan Brandão held that there was insufficient evidence to convict the defendants,” he said. “In the crime of homicide it is essential to have a body.” In addition, the key witness, Alves Neto, changed her earlier statement. Initially she had testified that she had seen Brandão Filho, Souza and another two persons that she did not know take Rocha away in a car that made off at high speed. She later changed her statement, saying that she had been taken to Salvador against her will and accused the detective of having forced her to testify against her will.

The district attorney said he suspected that the witness had been intimidated but nothing was done to protect her or prevent her being threatened. While currently it is difficult to find people to testify for fear of reprisals, in the early 1990s the situation was even more complicated, because there was no witness protection program in Brazil then. Campos said, “People imagine that it was a contract killing, but the person suspected of having masterminded it was never identified.” He recalled having read the judge’s sentence and called it “brave,” due to the fact that it was at a time when there was a lot of pressure.

Any police investigation can be frustrated, enough for a judge or police officer not to ask an important question, Campos said. In order to reopen the Rocha case, he went on; new evidence would need to emerge. For Campos, the investigation was carried out well, given the circumstances – Teixeira de Freitas had incorporated as a city only shortly before and at the time it had only one judge and one police officer, with all the deficiencies that implies. Currently, the city has a Legal Medical Institute and a court specifically handling criminal cases. In those days one had to wait days before a forensic scientist could make an examination, and by then it was too late.

Wilson Victor de Alcântara, the lawyer of Rede Sul Bahia broadcast network, the group to which the radio station that Rocha worked for belonged, followed case with the public prosecutor and accepted the acquittal of the defendants. “How am I going to seek conviction of someone if there is no evidence?” he asked. “To date we do not have investigators of a sufficiently high level for a crime of this nature. If the case were to be reopened, an in-depth investigation should be carried out, otherwise it is difficult.”

A decade later it is almost impossible to reconstruct what is left in the memory of the family and friends about the facts of the time. The mother, Valdelira de Jesus, upset at the loss of her son who had helped the family cope with a precarious financial situation, confuses facts and feelings. During the time when pressure from the press and human rights activists to solve the case was at its height, she announced that she herself had been the victim of an abduction.

She said that one night two men went to her home in a police car and took her away on the pretext that she had to make a statement at police headquarters. She said that she went in an airplane to Salvador and they began to put pressure on her to say that a congressman had given money to her son to run away. Presumably, Rocha had gone too far in his criticisms and the climate in the city was quite tense for him. Nervously, she recalled having had a very strong headache (she suffers from high blood pressure), so she drank a cup of strong tea to calm herself and she went into a deep sleep.

Friends and her daughter declared that she was in a state of semi-consciousness when she appeared on television in Santa Cruz to speak out against her own son. She does not remember that. On television she was interviewed about the fact the Ivan Rocha was not her son’s real name, but that it was Valdeci de Jesus. Ivan Rocha was in fact his cousin, whose name and identity he had assumed. The story was not confirmed by the family.

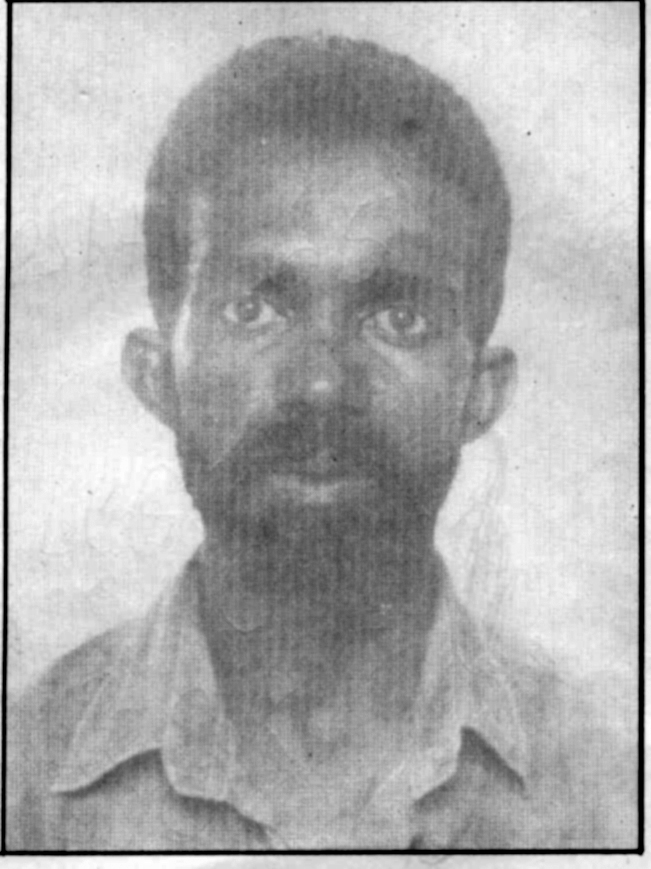

Ivan Rocha’s remains

A 1986 press credential of Rocha’s from Radio Santos Dumont radio station identifying him as a member of the Paraná Sports Reporters Association and a photograph of him at the Itabuna radio station that same year were the only mementos the family had. Given the years now gone by, it was not possible to find any information about Rocha in the files of those radio stations.

Due to the fact that Rocha served as regional head of the Bahia Professional Journalists Union in the extreme south under the name of Ivan Rocha, rather than his real name, the president of the Bahia Press Association, Agostinho Muniz, that the organization would only take part in the attempt to obtain information about the false identity once the announcer had reappeared. The name change was used as a pretext for Rocha to go from being the victim to being the guilty during the investigation, making prosecution of the case even more difficult.

Rocha’s mother said that he was 33 when he disappeared. He was the oldest of 12 siblings, of whom two had died while still young and two were killed by the police. Rocha helped the family out by providing rice and beans. He had left home at age 18 to live away from Teixeira de Freitas. He went to Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Belo Horizonte. He returned to Bahia when he was about 30 years old and helped build the house where his mother and sister now live. He had been at Radio Alvorado AM only a month before his disappeared. “I did not want him to do that program, it was dangerous, but he told me he had been born to do it,” his mother recalled.

For two years Rocha had his own newspaper, A Notícia, which stayed afloat thanks to a contract with the Mayor’s Office and because it opposed the administration of the group of the former Bahia state governor and re-elected senator Antônio Carlos Magalhães (PFL party). The mother recalls that he had run for city commission seat for the Workers Party (PT) in Itabuna city, Bahia.

According to his friends, Rocha always carried his phone number book with him. The day he disappeared, so did the book. He had left his mother’s home that day saying that he was going to meet his girlfriend, Rosária Monti, 34. When Rocha disappeared, Monti tried in vain to find any indication that would lead to him. “Everything disappeared – his notebook, documents and wallet. In the house where he was living nothing was found,” she said. She even thought he might have run away. She later began the battle to find her boyfriend.

Although they had been having an affair for a year, Monti did not know much about Rocha’s personal life. They met when he was working at the newspaper and she was leading a teachers strike. “He was an extremely good person and he wanted to continue with denunciation program on the radio,” Monti said. “He had an exaggerated way of presenting the news to call attention that I did not agree with but he never said anything that he was not certain about.” Her determination to discover what had happened to her boyfriend resulted in political persecution against her, losing her job and having to leave town.

The case goes to the Ministry of Justice

The last time that Josephus Julins Maria Koopmans, known as Father José, was interviewed by Ivan Rocha he advised the latter, “Ivan, watch out!” Father José said that Rocha sometimes made allegations without having any evidence to back them up. Rocha himself would have replied, “Sometimes I exaggerate, yes.” Father José acknowledged that “he was a brave journalist, without a doubt.” The area was always rife with situations that needed intrepidity. At the time that Rocha was working at the radio news about land disputes, police violence and political persecution with threats were frequent. Today, the problems are mainly centered on drug trafficking.

In the last 20 years Father José has led the fight for human rights in southern Bahia, denouncing cases of torture and death. “People who live near the police station and could hear the screams were not brave enough to report the matter,” he said. As a result of his political activities, Father José received a number of “messages” warning him to “take it easy.” As the residents were afraid to testify, for a long time he was the one who received all the complaints. “After the Ivan Rocha case we changed tactics,” he said. “Now, if someone wants to file a complaint he has to do so personally.”

Father José first met Rocha when the latter began going out with teacher Rosária Monti, whom he affectionately called Dadai and who also took part in the battle for justice. Because of his relationship with Monti and indignant at the way in which Rocha had disappeared, Father José launched a campaign to demand that the authorities investigate the case. Born in Holland, educated in Austria and with many contacts abroad, Father José channeled protest letters to the Brazilian government. As a result, he met in 1991 with then Justice Minister Jarbas Passarinho.

Getting no response from Brasília, Father José asked the minister to put the Federal Police on the case, but the official explained to him that this was not possible under Brazilian law except in cases of international drug trafficking. “The minister said he was concerned at the negative repercussions of the radio announcer’s death for the image of Brazil abroad and he asked his secretary to arrange a collective meeting with the representatives of the country’s leading newspapers so at least the case could be brought out into the open,” Father José said. The following day, reporters from the major news media were all there. The irony was that not a word was published. Only eight months later did the nationally-distributed Veja magazine mention the Rocha case as an example of violence in Bahia state.

A solidarity committee was set up in April 1991 by representatives of unions and human rights organizations to put pressure on the authorities to identify Rocha’s murderers. The committee was headed by José Alberto Ranciaro, 54, known as Zé de Baiana. He and his wife for the last 12 years have run a cultural center in São Lourenço, a poor neighborhood in Teixeira de Freitas, where they provide children and teenagers with professional courses to fight school drop-out. It was through Monti, a member of the adult literacy group, that Zé de Baiana met Rocha.

Zé de Baiana helped organize a public demonstration by some 5,000 people in protest at Rocha’s disappearance. He was hounded and attempts were made to intimidate him. He said that after organizing the rally he was followed on the street for several days, what he sees as a form of intimidation. Refusing to be intimidated, he went on to organize with Father José a kind of human rights office in the area.

In Zé de Baiana’s view Rocha was imprudent, because he had been warned of the risks he ran in airing his allegations. The program “A voz de Ivan Rocha” was broadcast simultaneously by three radio stations, so it had a guaranteed audience. On Rocha’s death, the radio station spokesman became Ramiro Guedes Luz.

In the first year following Rocha’s disappearance, Luz aired continuous music, with lyrics that would ensure Rocha’s fate would not be forgotten. He used lyrics from the song “Lost and Found” of composer Luis Gonzaga Júnior, interpreted by the strong, dramatic voice of singer Maria Medalha) – “Who will tell me where so-and-so is, friend, brother, boyfriend, who never returned? Keep on putting it in our newspapers, in the Lost & Found, Deaths, Too Many Memories sections.” He would go on to say to the authorities, “Today marks the XXX day since the disappearance.” A phone number to call with any information was then broadcast.

Luz’s insistence brought him telephoned threats. “They would say I would end up like Rocha, it was rumored that they had hired someone to kill me, but I never believed that,” said Luz, who is now the news director of Radio Transamérica radio station and editor of O Diário newspaper in Porto Seguro, as well as host of the Rádio Caraipe program “Almoço à Brasileira” (Lunch, Brazilian Style) in Teixeira de Freitas.

Decade of violence against press freedom

Rocha’s disappearance is regarded as the first recent case of violence against freedom of the press in Bahia, says Agostinho Muniz of the Bahia Press Association. Until 1991 there were few incidents of journalists being murdered in inland towns and cities. From 1991 to 1997, including Rocha, 10 were killed in doing their job as journalists in Bahia. Twelve years after his disappearance, Muniz believes it can be said that Rocha is dead.

The most critical period was 1995-97, when on average one journalist was killed every six months. In 1996, those figures attracted the attention of the Bahia Press Association, which held the First Seminar Against Violence on Press Freedom in Bahia. The Brazil Bar Association set up a committee for the defense of journalists under threat. The following year, the Second Seminar was held, with the participation of 13 local and international human rights and communication organizations. “It was a triumph, because the state government was very involved in this situation and even so we managed to attract representatives of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, who were under the influence of the politics of the day,” Muniz recalled.

Muniz believes that cessation of the murder of journalists in the state of Bahia was due to the action of those organizations and to an international outcry. The latter occurred in January 1998, when Manoel Leal, editor of the daily newspaper A Região in Itabuna, was murdered. However, Muniz says, there are still threats being made to journalists. Press and human rights organizations are now demanding that the authorities assume responsibility for the deaths, as the state constitution says that the government must guarantee freedom of the press.

|