September 8, 1986

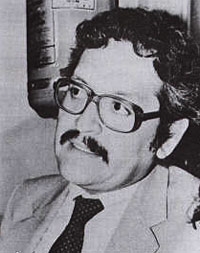

Case: José Carrasco

|

Journalist’s murderers convicted in Chile:

January 20, 2007

Mauricio J. Montaldo

Director Costa-Gavras won a 1969 Oscar for his film Z, which tells the story of a journalist who investigates violent crimes against opponents of the Greek dictatorship but ends up discovering that these crimes were committed by members of the military and police. In real life, a similar story comes to a close in Chile.

Twenty years after the fact, the curtain that had been held up by impunity and a malevolent silence came falling down on December 30, 2006. A Chilean justice system found and convicted those responsible for the murder of journalist José Carrasco Tapia, known by his friends as “Pepone” or “Pepe.”

This was the last violent crime committed against a journalist during Chile’s military regime. In the early morning hours of September 8, 1986, two armed men with their faces uncovered broke into the Santiago home of the metropolitan representative of the Chilean Journalists Association and international editor of the opposition magazine Análisis. Carrasco was beaten and forced out of the house while still in his pajamas. His two sons, ages 16 and 14, could only stand by and watch, stunned and helpless.

A curfew was in effect that night in Chile. One day earlier, a commando group from the underground Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (FPMR) had tried to assassinate dictator Augusto Pinochet in El Melocotón, in the mountainous outskirts of the Chilean capital. Though Pinochet survived the attack, five of his guards were killed, and the National Intelligence Center (CNI), headed by Gen. Humberto Gordon, ordered a “reprisal operation” to “make an example.”

The curfew was ordered and the city was immediately militarized. Under the curfew order, no one was allowed to move about in the wintry darkness of Santiago. All violators would be arrested, and anyone disobeying an order to halt would be shot. Yet the vehicle that the assailants had parked in front of Carrasco’s house, and to which he was dragged—as well as another car that followed behind—met with not the slightest hindrance as they sped along streets patrolled by uniformed officers from the Bellavista neighborhood, where the journalist lived, to the wall surrounding the Parque del Recuerdo cemetery. They were not stopped by anyone or anything.

Carrasco Tapia’s body fell against the wall in a hail of 13 bullets—12 in the chest and one in the foot—in addition to one that struck the wall. He was 43 years old. Two years earlier he had returned to Chile from exile. Just a few feet away, three other opponents of the dictatorship met the same fate: professor Gastón Vidaurrázaga Manríquez, 29, a visual artist and son of the head judge in the 11th Large Claims Court in Santiago; electrician Felipe Rivera Gajardo, 45, who worked at the Chilean Treasury Office; and advertising executive and accountant Abraham Muskatblit Eidelstein, 40. All of them were well-known opponents of the dictatorship.

This crime of vengeance shocked the nation and the world. One week later, the Chilean Journalists Association filed a criminal complaint for the murder of Carrasco Tapia. The same association filed a second complaint in 2006, but the courts dismissed it on the grounds that only the victim’s family members could file it.

The case was originally heard by Judge Aquiles Rojas. He soon had to be replaced due to illness—but not before he banned the media from reporting on the trial on the grounds of what he called “excessive publicity about the case.” This was the darkest chapter in the Chilean justice system. Gag orders foster confusion and obfuscation, and this one lasted more than five years, making it longest of its kind in Chilean history. “Prohibitions of this nature are temporary by nature, and extending them benefits criminals more than victims,” stated one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys, Nelson Caucoto of the Catholic human rights organization Vicaría de la Solidaridad.

Following a motion filed by the Chilean Journalists Association on September 9, 1996, with Supreme Court Chief Justice Servando Jordán—as well as pressure from the media, news professionals, and even journalism students—the replacement judge, Juan Manuel Escandón, was forced to lift the gag order on September 12, 1996.

Journalist Olivia Mora, Carrasco’s ex-wife and the mother of his two children, wrote a descriptive account 10 years ago in the book Morir es la Noticia (Death is in the News, published by Ernesto Carmona Editor). The book, which is excerpted on the Web site www.memoriaviva.com, states that “though Chileans had become accustomed to living without justice, surveys showed that people had negative feelings about law enforcement.”

Mora also wrote that “in the Pepe Carrasco case, the imposition of silence was an obstacle on the road to the truth. It appeared that the case was slowly on the way to being forgotten.”

Human rights attorneys Carmen Hertz and Patricio Hales, who filed criminal complaints, said that everyone knew who the culprits were: “We know where to find them and we can assume they were being paid. All we need is their names.” But just a few hours after the killings, Francisco Javier Cuadra, the general secretary of the administration and spokesperson for the military regime, dismissed the murders as an “internal struggle between Marxist factions over the failed attempt to assassinate Gen. Pinochet.” Now, however, Cuadra says that despite his senior position in the government, he did not know everything that was happening in Chile. He admitted to the newspaper La Nación that “there were acts committed as part of a conspiracy of some kind to commit crimes outside the authority of the government, and I do not approve of it or condone it.”

Judges at the time could get nowhere in investigating human rights violations. They were operating between submissiveness and fear. Their promotions were questioned, their decisions were overturned, they were transferred from one jurisdiction to another, military justice took precedence over civil and criminal justice, etc.

The trial was moved by judicial authorities to the court of Judge Dobra Lusic. Based on evidence that had accumulated over 13 years, and with democracy in full effect in Chile, Judge Lusic ruled on November 9, 1999, that the September 1986 abductions and murders of the four opponents of the regime were an act of revenge for the attack on Pinochet’s entourage. She even ordered that Gen. Humberto Gordon be remanded for trial. Gen. Gordon remained in custody in the Military Hospital until his death in June 2000.

In April 1996, Judge Lusic recused herself due to a backlog of cases, and the investigations were left unconcluded. The Carrasco case then landed in the court of Judge Hugo Dolmestch, who was also presiding over the so-called “Operation Albania” case involving the June 1987 murder of 12 leftist opponents of the regime. That massacre had apparently been carried out by the same CNI commando group that had killed Carrasco.

Judge Dolmestch expedited the case, ordered new investigations, and gradually connected the dots to conclude that government agents had carried out the murders. As the evidentiary phase was winding down, the judge was forced to step down from the case when he was appointed to the Supreme Court. At the end of 2006, it was Judge Haroldo Brito who finally issued a verdict in the case. Fourteen former agents of the military government’s intelligence agencies were convicted. At long last, the murders of Carrasco and the other three opponents of the regime would not go unpunished.

Sentenced to 18 years in prison for aggravated murder was the former chief of operations of the CNI, Maj. Álvaro Corbalán Castilla, who is currently serving a life sentence for other human rights violations. Also sentenced were other former members of the secret military agency: Capt. Jorge Vargas Bories and Col. Iván Quiroz Ruiz, sentenced to 13 years for their involvement in the Carrasco and Muskatblit murders; Army Col. Pedro Guzmán Olivares and Det. Gonzalo Mass del Valle, sentenced to eight years for the Rivera murder; Lt. Col. Krantz Bauer Donoso, Jorge Jofré, and Juan Jorquera, also sentenced to eight years in prison for the murder of Vidaurrázaga; former agents Víctor Lara Cataldo and René Valdovinos, sentenced to five years and one day in prison for the Rivera murder; and agents Víctor Muñoz Orellana, Eduardo Chávez Baeza, Carlos Alberto Fachinetti, and José Ramón Meneses, also sentenced to five years and one day in prison.

The ruling also ordered the government to pay 250 million Chilean pesos (approximately 500,000 U.S. dollars) in civil compensation to each of the seven plaintiffs, who are the victims’ widows, mothers, and children.

Though Judge Brito’s ruling was announced on the last day of 2006, the process of officially notifying the parties lasted until early March, from which point they will have five days to appeal the ruling. “I am confident that because the lower-court decision was unassailable, both in form and in the thorough investigation by Judge Dolmestch, the ruling will be fully upheld,” says Olivia Mora.

Observers wondered, “After 20 years of severe delays, what finally caused the Chilean justice system to stand up and issue a conviction? In Mora’s opinion, “the judicial branch was heavily criticized for its obsequiousness under military rule. With the restoration of democracy in Chile, all cases have been expedited, as we have seen in Pepe’s case and other rulings by the Supreme Court.” She also recognized that “the Chilean Journalists Association never lowered its guard throughout the long wait, and was always there to remind everyone that the case was pending.”

EXILE

A few months after the September 11, 1973, military coup in Chile, journalist José Humberto Carrasco Tapia, an active member of the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR), was arrested on charges of “carrying out political activity.” Apparently he was charged and tried in a secret trial. He was never interrogated, and we don’t know how that case turned out or how the military judge ruled. He was tortured at the Talcahuano Naval Base and then sent to Villa Grimaldi, a notorious secret prison of the intelligence agency DINA in Santiago. He was later transferred to Puchuncaví, another prison camp for political prisoners. Two years later, in 1976, he was released without charges. He then decided to take up exile in Venezuela, where he worked at the newspaper El Diario de Caracas. Though he never stopped thinking about returning to Chile, he soon moved to Mexico.

As he had received threats from Chile, his friends and colleagues always urged him not to return because of the huge risk he would surely be running if he entered the country under the dictatorship. But he ignored the dangers and fulfilled his intentions in 1984. Carrasco arrived in Santiago as part of the work team for Análisis, then a newly founded, pioneering magazine of the opposition. He was also a correspondent for the Mexican newspaper Unomásuno and wrote for the Argentine magazine El Periodista, where his last article, titled “Censura a la prensa independiente” (Censorship of the Independent Press), was published one week after his murder. In it he denounced the escalating repression of the opposition press. In an interview with Prensa Latina reporter Nicolás Lucar just one week before being murdered, Carrasco said, “We love life and we love peace, but more than anything we love justice and freedom. We are willing to give our lives for them.”

“Up until he went back to Chile, his apartment in Coyoacán [a Mexico City neighborhood] was a real hub of activity. Pepe was always nice, sweet, and affectionate with our children,” his ex-wife recalls. “On his frequent travels, he never failed to write them to give them advice and tell them about his experiences,” she added.

Carrasco was very close to his sons. Just minutes before saying goodbye, he repeated to them that they needed to study hard and do well on their final exams, so that their mother would let them travel to Chile to be with him. “The children went outside with him to say goodbye, and the last time I saw him was from the living room window,” Olivia says.

Three months later, she finally agreed to let their sons move from Mexico to Chile to live with their father. They happily made the trip just before Christmas, and Pepe was thrilled. He sent a letter to Mexico telling them how happy he was to welcome them and share life with them in their homeland.

SECOND DEATH

When in mid-1989 young Iván Carrasco Mora was summoned by the judge to identify his father’s abductors in a lineup, he showed that he had not forgotten. With no hesitation, he identified the men who on that fateful morning dragged his father half-dressed from his bedroom without giving him the chance to tie his shoes. “You won’t need them,” one of them said. Iván identified Jorge Vargas Bories, whose defense team tried to discredit Iván as a witness, claiming that because he was a minor at the time, he could not remember faces and clothing. But Iván was absolutely certain about the person he had just identified.

His brother Luciano, who was 14 at the time his home was invaded, never got over what he experienced that morning. It pained him to see how the years passed and the justice system failed to solve his father’s murder. And besides, nothing could replace the loss of his dear father. Iván recalls that Luciano “could never get over such a brutal, horrifying incident. It continued to haunt him as an adult, and shortly before his 31st birthday in 2002, he finally threw himself in the path of a train.” He left behind his mother, wife, 10-year-old daughter, brother, and friends. The cruel force of impunity had driven him to desperation.

|