June 2, 2002

Case: Tim Lopes

|

Tim Lopes’ death shows how powerful the drug traffickers are:

June 2, 2002

Clarinha Glock

Wearing shorts, an old yellow shirt and sandals, like a typical resident of the hillsides of Rio de Janeiro, reporter Tim Lopes, 51, left the TV Globo television station on June 2, 2002, on his way to what turned out to be his last big investigative reporting assignment.

Wearing shorts, an old yellow shirt and sandals, like a typical resident of the hillsides of Rio de Janeiro, reporter Tim Lopes, 51, left the TV Globo television station on June 2, 2002, on his way to what turned out to be his last big investigative reporting assignment. He carried a miniature camera hidden in his fanny pack to film a funk dance in the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown, one of 12 slum areas on the hillside known as Complexo do Alemão in the Penhan neighborhood, a Rio de Janeiro suburb. Lopes had received a complaint from residents of the shantytown that in the parties there organized by drug traffickers there was sexual exploitation of minors and drug abuse. The residents were asking for help.

It was the fourth time that Lopes would go up to the shantytown to do the report. On the first two occasions he did a reconnoiter of the area. On the third, he took his mini-camera but the images were not regarded as good enough to use as evidence - and he had no pictures of the party itself. That is why we went back. He had arranged that the driver hired by TV Globo especially for the assignment would go and pick him up on the hillside at 8:00 p.m. At the pre-arranged time, however, Lopes said he would need more time to finish the job and asked him to come back at 10:00 p.m. The driver came back at that time, but Lopes did not turn up.

Marcelo Moreira, 32, TV Globo chief reporter in Rio de Janeiro, said that when the driver called the newsroom to report that Lopes had not appeared, he was told to wait until midnight.

“The question of timing is important, but as it was a funk dance he had gone to we thought the event had been prolonged because of the Brazil soccer game (in the World Cup finals),” explained Ali Kamel, 40, TV Globo news director.

Moreira arrived earlier than usual at the newsroom, around 4:00 a.m., as the game was to start at 6:00 a.m. “When we thought something might have gone wrong, we called everybody,” he said.

What followed was the start of a search for Lopes that ended a week later with the announcement of his death and the exchange of accusations between the local and national authorities in the attempt to identify the perpetrators and blame the failure to do so on the power of the drug traffickers.

Lopes’ death was confirmed following the arrest of Fernando Sátiro da Silva, a.k.a. Frei, and Reinaldo Amaral de Jesus, a.k.a. Cabê, two members of the drug trafficking unit led by Elias Pereira da Silva, a.k.a. Elias Maluco, one of the leaders of the Comando Vermelho crime gang that rules the Complexo do Alemão shantytown complex. Statements made by the two arrested men indicate that Lopes might have been identified by drug traffickers as the writer of a report titled “Drug Party” broadcast by TV Globo in August 2001. In the report, Lopes used a hidden miniature camera to film drug deals on a street in the area. After the report was broadcast, a number of drug traffickers were jailed and their business halted, to their detriment.

According to statements made to police, drug traffickers were believed to have taken Lopes from the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown to the one named Grota, where Elias Maluco was. There, he was said to have been “put on trial” to determine whether he should be killed. Lopes was badly beaten and tortured. His body was dismembered and burned with automobile tires in a cave, a method known as microwaving and often used by drug traffickers to kill police or informers and to eliminate any evidence that could identify the murderers.

The arrest of Elias Maluco, who came to be known as “the most dangerous crook in Rio de Janeiro,” and of the other alleged murderers was held to be a “question of honor” by representatives of the Rio de Janeiro state government. For a week police staged daily raids on the hillside in search of Lopes’ body, those responsible for his death and witnesses that could lead them to the murderers. As of June 17, 2002 police had identified nine members of Elias Maluco’s gang who they said took part in Lopes’ murder. Two are now in jail.

Ângelo Ferreira da Silva, arrested on June 13, confessed that he was in the Palio automobile that he said took Lopes from Vila Cruzeiro to the Grota shantytown where Elias Maluco was. He said Lopes was tied up and had a gunshot wound in the leg when he was put into the car. He described the torture to which Lopes was subjected but said he was not present when he died. He named two others involved in the murder.

Elizeu Felício de Souza, a.k.a. Zeu, arrested on June 14 and said to be one of Elias Maluco’s bodyguards who allegedly took part in Lopes’ execution, confessed that he had bought gasoline and diesel fuel at a gas station near the entrance to the Nova Brasília shantytown, which is part of the Complexo do Alemão complex. Zeu said he understood that the body of some enemy of the gang was going to be incinerated, but he could not confirm that it was Lopes.

The search goes on

The Rede Globo television network, through its affiliates throughout the country, its cable TV service, its newspaper and radio stations, launched a campaign to find the “Enemies of Rio,” as it called Lopes’ killers.

The media have helped publicize a telephone hotline called Disque-Denúncia for anonymous tips sponsored by the state government and the Rio Anti-Crime Movement, offering a 50,000 reais (nearly $20,000) reward for information on the whereabouts of Elias Maluco. Posters with the telephone number (21-22531177) were placed on the back windows of city buses. The police have not ruled out that Elias Maluco is hiding in a Rio shantytown or in some other state.

The reporter’s safety

The Lopes case has been characterized by a number of irregularities. Journalists and police criticize each other. One of the criticisms concerns the time TV Globo took to report Lopes’ disappearance to the police. The police say they were advised only around 8:00 a.m. the following day. “We sent someone to make the report at the police precinct and he arrived there at 8:00 a.m. But before that we had already called the Military Police station in the shantytown,” TV Globo’s Moreira said. “However, the police did not get to the shantytown until 1:00 p.m. on Monday, June 3.”

Others criticize the lack of security measures to rescue the reporter in case of an emergency during his newsgathering. “Tim was not one to take risks, if he had been threatened I am sure that he would not have gone back to the place,” Moreira said.

TV Globo news director Kamel said that the event Lopes was filming was a public one and he did not pretend to be a gang member or resident, so he did not need the same kind of security as he would if he had infiltrated some private function or closed premises. An eye-witness told TV Globo that he saw Lopes when he was being taken away from the dance and beaten. Kamel stressed that Lopes was not infiltrating, he was merely disguised as a local. “There, anyone would be killed if he went with a notebook in hand and the message is that the drug traffickers do not want the press on the hillside any more because that is not good for their business,” he said.

The way the reporter died, having gone to the shantytown district with no protection whatsoever, gave rise to a note from the Journalists Union committee that is following the investigations, saying, “In recent days, many of us have heard on the street, and even from our sources, comments that Lopes had been irresponsible in going into a shantytown run by drug traffickers the way he did, or he had been required to do so by his bosses. We remind those people, who know nothing about the way we work, that everyone is aware of the fact of drug trafficking in the hills, including the police, and many journalists have talked about it.”

TV Globo appointed an in-house committee to review its coverage of violence in Rio de Janeiro and security measures. Other companies have also begun to protect themselves. Following Lopes’ murder some reporters are going into the Rio hills wearing bulletproof vests. Even the use of armored cars has been considered. In newspapers and on television journalists question the use of miniature cameras and the ethics of investigative reporting.

The case has also led the Journalists Union and the Brazilian Newspaper Association to hold seminars on journalists’ safety.

Alexandre Medeiros, 41, a 20-year journalism veteran, was a friend of Lopes. He was writing a book with him on the samba and the Mangueira district of Rio, but stopped doing so after feeling threatened. “In the old days to be identified as a journalist was an assurance of getting special treatment. Today, it is like being a target,” Medeiros said. After Lopes’ death, he appeared a number of times on television, calling on the police to bring the guilty to justice.

An ineffective system

Drug trafficker Elias Maluco, the chief suspect in Lopes’ murder, had been arrested, tried and convicted in 1996. He is regarded as the cruelest of the drug traffickers and the main one at large from the Comando Vermelho gang. His casefile shows that in 1993 he humiliated and executed four officers from the Military Police 9th Battalion. In reprisal, police raided the Vigário Geral shantytown and killed 21 people there. Maluco is also accused of having invaded the Macacos and Pau da Bandeira slums, killing six people, injuring three others and evicting residents.

He is further accused of having plan to free another drug trafficker, Adair Marlon Duarte, from custody by using a wagon to knock down a wall at the jail where he was being held and of the kidnapping of a student, Eduardo Eugênio Gouveia Vieira Filho.

Despite all this, Elias Maluco was freed on bail in 2000 on a writ of habeas corpus. According to Rio de Janeiro District Court chief judge, Marcus Faver, the court ordered Maluco freed because he had been held in custody for too long and it wanted to avoid any accusation of undue privation of liberty.

The role of the police in the hills

Homicide Police Chief Paulo Passos and Detective Carlos Henrique Machado, who took part in the raids on the Complejo do Alemão complex in search of Lopes’ body and his murderers, said they had been unaware of the existence of a clandestine cemetery at the top of the Grota slum, where they found bodily remains, parts of a miniature camera with a Rede Globo sticker, a watch, a neck chain with crucifix, a knife and a shirt. Officials from TV Globo confirmed that the camera was the one Lopes had been using at the time of his disappearance. The chain and watch were also identified as having belonged to Lopes.

In the Complexo do Alemão complex, made up of 12 shantytowns, there are four Military Police units. They are the so-called Community Police Stations or Police Posts. One of them is located at the top of the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown, where the funk dances that Lopes was investigating are held.

Each shantytown is a kind of city. The topography of the hillsides, with their winding streets, makes them a good hideout for criminals. The people there in general know what goes on in their neighborhood. Information that reached the police via the tips hotline described, for example, how loud screams were heard the night that Lopes died, such that residents had to shut their windows so as not to hear them. There are stories from local people of “parades” through the shantytown of “traitors” or “crooks” beaten and tortured after being subjected to the drug traffickers’ “justice” and before being killed. One story has it that a police officer was brutally tortured when they found him trying to infiltrate a gang.

Although the police post is a long distance away from where the funk dance witnessed by Lopes was held, it is hardly likely that the police were unaware of the sexual exploitation of minors and drug use there. In the Grota clandestine cemetery there were found at least five jawbones, none of them Lopes’s, in addition to bone fragments.

The situation is so difficult that in an interview published in O Globo newspaper on June 23, the president of the Association of Military Police Non-Commissioned Officers and Soldiers, Vanderlei Ribeiro, said that there is a ruling by the commander-general prohibiting police from going into 15 shantytowns in Rio de Janeiro unless they are backed by elite forces, such as the Military Police Special Operations Battalion and the Special Resources Unit of the Civil Police.

The Rio de Janeiro under-secretary for Public Safety, Ronaldo Rangel, told the IAPA that the police officers who remain in the units located in the hills act only in response to complaints. He said there was no indication that the police knew of the “microwaving” or the clandestine cemetery, where staff from the Legal Medical Institute found bones from which they managed to reconstruct seven skeletons, later subjected to DNA testing.

The conditions in the shantytowns led Public Safety Secretary Robierto Aguiar on June 17 to announce that health and other social service centers are to be set up in the Complexo do Alemão complex, beginning with the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown. He said that the Grota shantytown, where Lopes was murdered, will be rebuilt, so that it will no longer serve as a clandestine cemetery for the drug traffickers. Aguiar pledged to use state-of-the-art geological and archeological devices in continuing the search for bodies in the cemetery. A month after Lopes’ disappearance, his body has yet to be found, the murderers remain at large and Aguiar’s promises remain unfulfilled.

Corruption and impunity aid crime

The murder of Lopes mobilized the police, politicians and the media thanks to the reach of the Rede Globo TV network. But not every violent death has had such repercussions as this. Other Brazilian journalists murdered while carrying out their work were not so prominently reported and investigations into their deaths remain stalled.

In Rio de Janeiro the murder of two other journalists are under investigation. The case of Mário Coelho Filh, from the newspaper A Verdade, murdered in August 2001 in Magé, in the region known as Baixada Fluminense, remains an open case, says detective Carlos Henrique Machado of the Homicide Division. However, Chief Detective Paulo Passos acknowledges that the investigation into the murder of Reinaldo Coutinho da Silva of Cachoeiras Jornal in Cachoeiras de Macacu in August 1995 is unable to continue due to the lack of new witnesses and the fact that it happened a long time ago.

Lawyer Cristina Leonardo, head of the non-governmental organization Brazilian Center for the Defense of the Rights of Children and Teenagers in Rio de Janeiro, sees Lopes’ murder as being different from the other cases that remain unpunished for one basic reason - “Generally, the police and the district attorney’s office, in order to muddy the investigations when the person is dead and the murderers disappeared along with the body, say that when there is no body, there is no crime.” On June 9, 2002, one week after Lopes’ disappearance, Police Chief Zaqueu Teixera officially announced that Tim Lopes was dead, even though his body had not been found. The police based this on statements made by detainees who denied having participated in the crime but described how it happened. “Often a murder does not need to have a body to be confirmed,” said the Homicide Division’s detective Machado.

It was only on June 11, acting on an anonymous tip-off, that the police discovered in the Grota shantytown clandestine cemetery the remains of TV Globo’s mini-camera and bone fragments, which were subjected to DNA testing at the laboratory of the Federal University in Rio de Janeiro. Forensic experts confirmed on July 5 that the remains belonged to Lopes. The remains were buried two days later in the Jardime de Saudade cemetery in Sulucap. Attending the funeral, in addition to friends and family, were state Governor Benedita da Silva and Civil Police Chief Zaqueu Teixeira.

Rio de Janeiro abounds in unpunished murders. In 1993, there was the in the Vigário Geral shantytown massacre. It was in reprisal for the slaying of police officers carried out on the orders of Elias Maluco. Lawyer Leonardo, the attorney for the relatives of people killed in the massacre, said that those responsible have not been brought to trial in two years because the defense attorneys keep being changed and each time the new counsel says he needs more time because he is not familiar with the case and asks for more probatory proceedings, calling police officers who will never testify and, mainly, threatening witnesses.

The pressure to speed up the investigation into Lopes’ murder brought sharp criticism from the police. “Fifteen days ago a civil policeman died at 7:00 p.m. He was 33 years old and he was also on the job. The Rede Globo TV broadcast only a brief item,” said detective Machado. “They are making Lopes out to be a God, but there are other crimes. We police officers are also victims and we don’t like this - there is a lot of collaboration by non-governmental organizations, but when a policeman is murdered I don’t see anyone at the funeral or giving support to the family.”

Parallel State

The fact that Lopes was “arrested” and “tried” by drug traffickers for having invaded their turf without permission and the discovery of a clandestine cemetery in the hills of the Complejo do Alemão complex led the federal authorities to declare that there is a parallel state in Rio de Janeiro’s shantytowns, ruled by the drug traffickers. This in turn led to an exchange of accusations between representatives of the federal and state governments as to who is responsible for Rio de Janeiro having come to this situation.

The chief of the Rio de Janeiro Civil Police, Zaqueu Teixeira, responded by saying that “there is no parallel state, what there is are conflict zones and legal obstacles that prevent the police from acting to apprehend anyone; for example, a court order must be obtained and this can take a long time to be issued.” Under-secretary for Public Safety Ronaldo Rangel said that the traffickers’ arms and drugs come from abroad and it is the Federal Police that controls the borders.

Retired Judge Walter Maierovitch, who heads the Giovanni Falcone Brazilian Institute of Criminal Science and who teaches specialist courses on organized crime and drugs, sees the situation in Rio de Janeiro in a wider way. “We are not talking about street gangs, these are special associations of delinquents that act against the rule of law and against individual rights and guarantees, which is a real national security issue, therefore within the competence of the federal government,” he said. Maierovitch likens those associations to the Mafia, because they have territorial and social control.

One opinion that stands out is that of a state congressman currently belonging to no party, Hélio Luz, who headed the Civil Police in Rio de Janeiro from 1995 to 1997 and dared to take on the power of the drug traffickers. According to Luz, the Complexo do Alemão complex exists because the Brazilian government needs it in order to remain in power and to keep the people marginalized in the hills. Luz even criticizes the role of the Roman Catholic Church and some non-profit organizations which, in his view, work in the shantytowns seeking to calm the situation without questioning the inequitable distribution of wealth that is the real reason for the misery in the shantytowns. Generally crime has always existed for the common citizen. The difference is that now it is reaching the middle class.

In Luz’ view, Lopes was murdered thanks to a violent and corrupt government which has no control over its internal institutions and its powers and whose prime duty should be to maintain control of its police in order to lower the crime rate.

Lopes’ death also served as a pretext for the Rio de Janeiro Chief Judge, Marcus Faver, to criticize the bureaucracy for impeding the administration of justice and allowing traffickers such as Elias Maluco to go free. “In Brazil, rights and guarantees are taken to such an extent that they become obstacles,” he said. “Why does the criminal have to be present in court, couldn’t only his attorney be there?” Faver said there are judges that sit in two courts while some courts have no judges at all. In his opinion the solution is to amend the penal and administrative process.

On June 11, 2002, the Federal Senate passed a number of changes to the Code of Criminal Proceedings with the aim of preventing cases such as that of Elias Maluco. The changes have still to be approved by the Chamber of Deputies. They include, for example, an obligation for a judge to justify his decision when granting habeas corpus, this annulling a jail order, as well as allowing judges to interrogate detainees at a distance - by closed-circuit television - to avoid having to sequester witnesses.

Impunity in Brazil is sometimes linked to electoral power, says Tânia Maria Salles Moreira, 50, public prosecutor for the Rio de Janeiro 7th Criminal Court. For 12 years she served as prosecutor in one of Rio’s most violent districts, the Baixada Fluminense.

In Rio de Janeiro, when candidates want to go into the shantytowns, they ask permission from the drug traffickers, who are the biggest employers there and thus are in a position of power. “The majority of the votes come from the communities under these gentlemen’s orders,” she said.

To be a journalist is a risky job in Rio

“Tim’s death was an effective assault. Today, you can imagine that all the newsrooms are in a state of fear and it is going to be hard to come up with a strategy to conquer that fear and keep us from being silenced. We are journalists, we are for the truth,” said TV Globo’s Kamel.

Reporter Marcelo Beraba of the Rio de Janeiro bureau of Folha de S. Paulo of São Paulo and chairman of the National Newspaper Association’s Press Freedom Committee, suggested that the Rio press should take up where Lopes left off. “We have to get to the bottom of Tim’s death and what he was investigating,” he said.

In a state where the middle-class lives side-by-side with shantytowns and clashes between police and criminals are a daily occurrence, it is impossible to ignore that Brazil is undergoing a civil war. To identify who are arms and drugs traffickers and the corruptors and the corrupted in any part of the world is synonymous with danger. In Rio de Janeiro, anyone targeted by the traffickers is marked forever. “You can’t make a mistake in such a case, it is bound to cost you your life,” says Aldir Ribeiro, 49, who now runs an educational television program in Rio de Janeiro. When he was a reporter for Manchete Television’s “Special Report” show he did investigative reporting and received a number of threats. “Every day I thought of giving it up,” he said. “You have no more peace, you think that everybody is looking you over.”

João Antônio Barros, 39, from O Dia, had a price on his head after spending some time inside the Bangu 3 Prison without identifying himself as a reporter. He did a report on corruption in the prison system and learned later that someone was prepared to pay 50,000 reais (about $20,000) to have him killed. “Fear you have every day, but if I don’t do the reports I’ll stop working,” he said. “I can’t imagine journalism without exposés.” Barros adds, however, that younger journalists do not go up into the Rio de Janeiro hills as the more experienced ones used to early on in their career.

Lopes’ murder should serve as an example, says Marcelo Leite from O Dia. “We should go after the Elias Malucos - not just in drug trafficking but in the judiciary, the police and politics,” he declared. Leite says that he had received the same complaint from the residents of the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown that was being investigated by Lopes about 15 days before he learned of his colleague’s disappearance.

“The murder of Tim Lopes was a pre-announced death,” says journalist Cristina Guimarães, 38, who is currently in hiding. In October 2001, she asked to be relieved of her duties at TV Globo, alleging that the company gave her no protection when she received death threats. She was the co-author of a report titled “Drug Party” with Lopes and another two journalists that broadcast in the television news program “Jornal Nacional” (National News) in August 2001. She went into the Rio de Janeiro Rocinha and Mangueira shantytowns with a miniature camera hidden in her purse to film drug trafficking activities. As a result of her coverage, a number of drug traffickers from Rocinha were jailed.

Guimarães was then informed that there were people keeping a watch on her workplace and one of them had said that drug traffickers were offering 20,000 reais (about $8,000) for her head. Some 10 days later, on reading the newspapers she learned that a member of the staff in the TV Globo sports department had been kidnapped by traffickers from Rocinha and they wanted to know who had written the “Drug Party” piece. The facts were noted by the 15th Police Precinct.

Anxious and scared, Guimarães decided to leave her job. She filed lawsuit against the company and quit in November 2001, then sought help from Amnesty International to leave Brazil.

Her lawyer, Cristina Leonardo, in June 2002 asked the secretary of Public Safety and the Federal Police superintendent for the Guimarães case to be investigated. She fears for the reporter’s life and now links Lopes’ murder to the death threats her client received.

A former staff member who produced the TV program “Linha Direta” (Direct Line) is also in hiding and in fear of her life. The program features unsolved crimes, re-enacts them and names those suspected of committing the crimes, and asks the public to help find them. The producer, who asked not to be identified, said she used a hidden camera and was pressured on more than one occasion to go out and do risky reporting.

“Since the moment I joined ‘Linha Direta’ I began receiving threats and I used to joke with people, saying they would have to get in line to kill me. The only time I was scared was when I could not be what the TV directors wanted me to be,” she said. The final straw was when she began to investigate the activities of drug traffickers and a death squad in Baixada Fluminense. The district attorney who investigated the case warned the reporter to get some protection, because she had already been threatened and this story could put her life at risk.

One day, as she was returning to the television studios, she said she noticed an automobile with armed persons in it just ahead of her. She called for protection but the program director said there was no need for it, and that could alarm other reporters.

Asked about cases such as this one of the TV producer, César Ceabra, regional editor of TV Globo in Rio de Janeiro, assured that “when it is necessary, the company provides security.” Luis Erlanger, director of the Globo Communication Center, recalled that several reporters form TV Globo had been sent to other states or abroad because of their being at risk. In some cases, private bodyguards are hired to accompany a threatened reporter. In the case of Guimarães he was emphatic: “If we had known about it, we would have taken precautions.” In the lawsuit filed by Guimarães against TV Globo, the judge agreed to her quitting the company but he did not take up the question of her protection.

An example of dignity in journalism

Tim Lopes was at one with his colleagues. The day that the bone fragments and neck chain (later identified as being his) and pieces of the mini-camera bearing a TV Globo sticker were discovered, the reporters and photographers at the scene joined hands, prayed and wept. Later a public ceremony organized by the Rio de Janeiro Journalists Union and the National Newspaper Association was held in downtown Rio de Janeiro. In it, the authorities were urged to find Lopes’ body and bring the guilty to justice. His colleagues at TV Globo concluded the main news cast of the day dressed in black and giving a round of applause in his memory.

Many outpourings are due to the fact that Lopes, known for his humble and playful ways, was admired for his brilliant reports and his courage in bringing to light what was happening in the shantytowns that he himself, raised on the Mangueira hillside, the son of a poor family, knew all too well. “Tim was what is most noble about the profession - someone who was always seeking justice, helping the needy, getting the news at first-hand, making a difference,” said César Seabra, 41, of the TV Globo regional bureau in Rio de Janeiro.

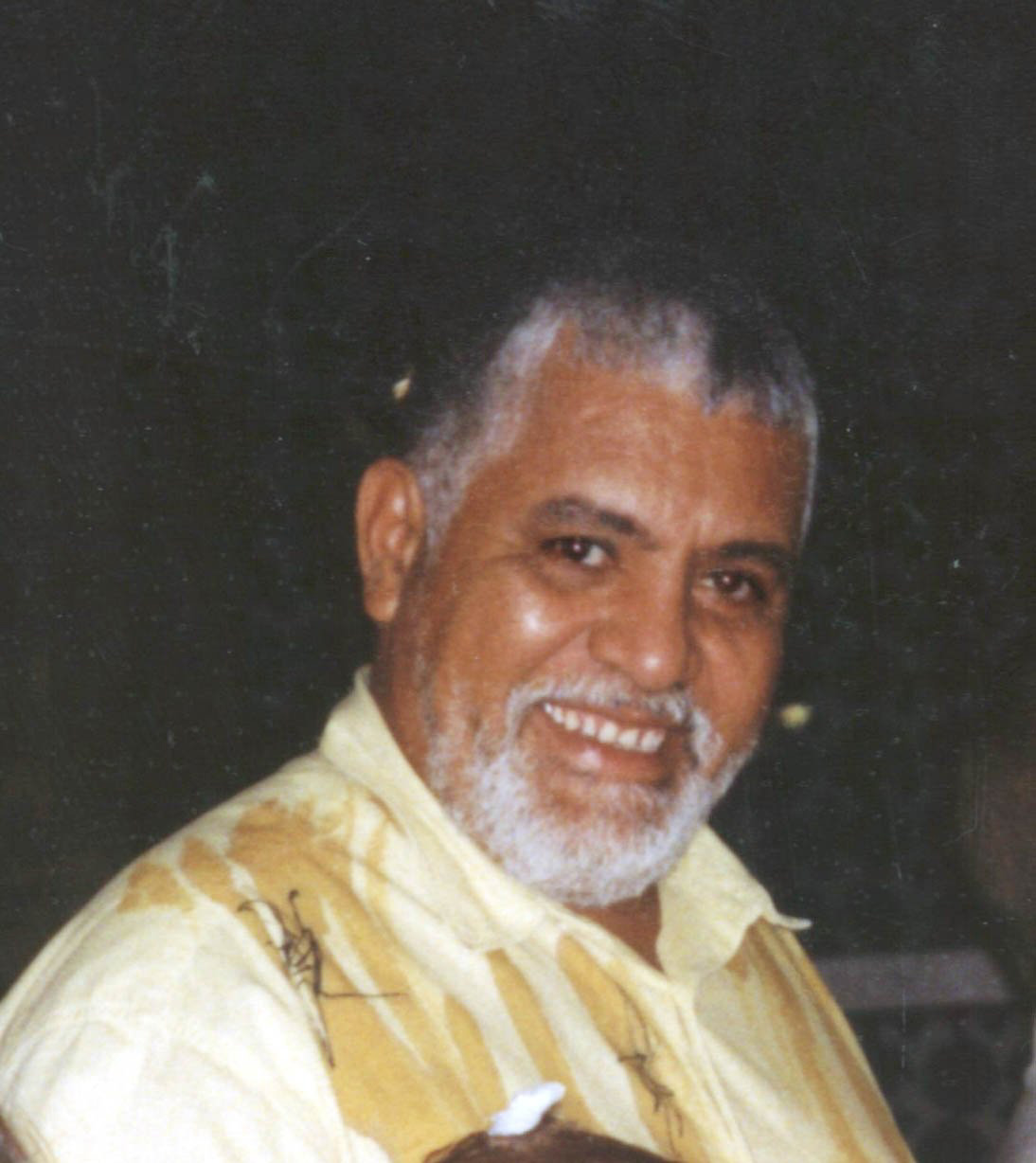

Photographer Marcos Tristão, who had worked with Lopes at the newspaper O Dia, jokingly says you can see several Lopeses on the streets of Rio de Janeiro, because he looked like a typical carioca (native of Rio). Of mixed race, in recent times with a pot belly, Lopes had a big smile on his face and the manner of someone who could get away with anything. That is how he pretended to be a beggar so that he could get close to street children and report on what their lives were really like in a piece for Jornal do Brasil. For another report, he became a blue-collar worker and for yet another a homeless person, recording his experiences in O Dia.

“I have always sought to investigate, in-depth, people’s souls,” he once said. For that reason he hardly reported on the people’s dramas. He discovered talent that he placed on television and encouraged, through his reports, community projects such as programs to prepare young African-origin students for university in the Baixada Fluminense district. Thoughtful when discussing a delicate matter, he always began a sentence the same way - “Good judgment says that ….”

In one of the first reports he did for TV Globo, Lopes dressed up as Santa Claus and reported on what people were dreaming of. He got admitted to a drug rehabilitation center and reported on the drama of the patients’ lives. To the viewers of the country’s leading television network, however, Lopes’ name was barely known, because he concentrated on doing the newsgathering job behind the camera, without showing his face, and in this way showed what everyone either distrusted or knew already but no one had the courage to voice. Thanks to such courage he won an award along with his crew for the “Drug Party” report, in which using a mini-camera he taped open drug deals in the Complexo do Alemão complex, in a shantytown near the Vila Cruzeiro one where he died.

In a talk to journalism students once he said that when he was looking for news while he was investigating the facts he was able to stay cool, but later got scared. In his last investigative report, however, his instinct told him that the risks were great. The week before disappearing he told his wife, Alessandra Wagner, that the Vila Cruzeiro thing was more dangerous than in the filming of the “Drug Party” and that he was going out on a thin limb. He was beginning to think of giving up doing that kind of reporting. He had already said that once this job was done he was going to go with a truck driver on a trip to report on it for the “Globo Repórter” program.

A Gaúcho (meaning he was born in the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sol) but raised in the Mangueíra shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, he always liked the samba and carnival and paraded in the group calling itself “Simpatia é quase amor” (Sympathy Is Almost Love). He read a lot. “He always said he would like to write a novel based on the experiences he had as a journalist,” recalls lawyer André Souza Martins, Lopes’ brother-in-law. Since 1999 he was co-authoring, with journalist friend Alexandre Medeiros, a book titled “Eu sou o samba” (I Am the Samba),” portraying profiles of famous Rio samba performers.

The funk in Tim Lopes’ view

In 1994, Lopes wrote a series of reports for the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Dia on funk dances. The series won an award as the best report published in the paper that year. In the same period, Lopes went on to write a weekly column on Fridays in the Culture supplement about people and events in the funk world. Since then, the dances have changed, along with the shantytown drug dealers. This year Lopes would not be reporting on the dances as such but on the heavily-armed youths that frequent them, the use of drugs and the sexual exploitation of minors. Ironically, eight years after the first reports Lopes returned to a funk dance which cost him his life.

On February 27, 1994, he wrote about another kind of violence associated with the dances:

“Here, south of the Equator, in the narrow streets of the Complexo do Alemão the funk rhythm has other names but it too is linked to pleasure, letting loose and violence. But funk is not just music. It is a way of life …. They own the street, the neighborhood, the city, all of it. They are always ready to win any battle, face anything. That way they exploit conflicts among groups. In the past three years more than 50 young people have died in fights between funkers and hundreds have been injured. The funk world has room for sticks, stones and firearms, it embraces nomadic tribes that scatter joy and terror. It is a life-and-death ritual.”

Arcanjo Antonino Lopes do Nascimento (Tim Lopes)

(November 18, 1950 - June 2, 2002)

Date of death: He disappeared on June 2, 2002. Statements made by two arrested drug traffickers indicate that he was murdered between 10:00 p.m. and 12:00 midnight of June 2, 2002.

Place and circumstances of death: Around 5:00 p.m. on Sunday, June 2 Lopes set out for the Vila Cruzeiro shantytown in the Penha neighborhood, a suburb of Rio de Janeiro, with a miniature camera hidden in a fanny pack that he wore on his waist to tape a funk dance organized by drug traffickers. He had received a complaint from the residents of the shantytown that at the dance there would be sexual exploitation of minors and the sale of drugs. He was also going to investigate a report that the drug traffickers were building a children’s park in a road leading to the shantytown to make it difficult for police action and that they were parading around armed with rifles.

Probable cause: Lopes’ presence at the scene puzzled the drug traffickers. There is a suspicion that once his identity was discovered his death was a certainty in reprisal for a previous report on drug dealing in the shantytowns broadcast in August 2001 by TV Globo. Following that report, several drug traffickers were jailed and drug dealing in the area suffered a setback for a while. Another theory is that Lopes was taken to be a police officer or informer.

Suspects: According to witnesses, Lopes’ death was decided by drug trafficker Elias Pereira da Silva, a.k.a. Elias Maluco, one of the leaders of the Comando Vermelho crime gang ruling the Complexo do Morro do Alemão complex, comprising 12 shantytowns. Investigations indicate that eight other traffickers from his gang took part, among them, André da Cruz Barobsa, a.k.a. André Capeta, Ângelo Ferreira da Silva and Elizeu Felício de Souza, a.k.a. Zeu. Prior to the murder, the drug traffickers held a kind of trial to decide on whether Lopes should be killed, and he was tortured before being put to death.

PERSONAL FILE

Place of birth: Pelotas, Rio do Grande do Sul state, Brazil

Age at death: 51

Marital status: He had lived with Alessandra Wagner for the past 10 years

Children (names and ages at time of father’s death): Bruno, 19, son by his first marriage, and Diogo, 15, Alessandra’s son

Education: Journalism studies at the Hélio Alsonso School, Rio de Janeiro

Profession/position: Reporter and network producer for TV Globo since 1996

Background in journalism: He first worked at Samuel Wainer’s magazine Domingo Ilustrada as a messenger. When he started street reporting he came to be known as Tim Lopes. According to friends, Wainer gave him this pen name. He worked at the now defunct newspaper O Repórter, at the magazine O Placar, and at the Rio de Janeiro newspapers O Globo, Jornal do Brasil and O Dia.

Hobbies/leisure activities: He was fond of running on the beach. Once, in the São Silvestre race that was run traditionally on New Year’s Eve in São Paulo, Lopes ran with Minister João Sayad. He was a fan of the Vasco de Gama soccer team. He was the founder of the carnival group “Simpatia é quase amor” (Sympathy Is Almost Love).

Other activities or roles: He acted as a judge of the samba schools in the Carnival. He was writing a book with reporter Alexandre Medeiros on the samba and Mangueira, the neighborhood where he grew up.

Awards: In 2001 he was awarded the Esso Prize along with the TV Globo crew for a report titled “Drug Party,” in which, using a hidden camera, he exposed open drug dealing in the Complexo do Morro do Alemão complex. It was the first Esso award in the television category. He also received the 11th and 12th Abril Journalism Awards for spot news reporting with his reports “Tricolor de Coração” (Tricolor of the Heart), published in the magazine Placar in December 1985, and “Amizade sem Limite” (Friendship Without Bounds) written in May 1986. In February 1994 he won a prize for the best reporting in the newspaper O Dia for his series “Funk: som, alegria e terror” (Funk: Sound, Joy and Terror) - ironically, the same theme of his last report for TV Globo.

More information on the life of Tim Lopes is available on the Web site www.timlopes.com.br

|