November 11, 1984

Case: Mário Eugênio Rafael de Oliveira

|

Impunity, 17 years later:

August 1, 2001

Clarinha Glock

Almost 17 years after being sentenced to prison for the murder of journalist Mário Eugênio Rafael de Oliveira, police officer Divino José de Matos, known as "The Divine 45," has once again succeeded in escaping justice. Despite the fact that earlier this year his sentence was upheld, he was still free as of July 23. "We have not halted and we plan to tap his telephone," said police detective Elói Nonato da Silva, of the Inter-State Capture and Police Unit, who is in charge of putting Divino in prison. He admitted, however, that no special action had been taken to jail Divino although it had been known for some time that he intended to ignore the court sentence. "The court has not told what decision it is going to take nor the day and time," he explained.

A number of police officers identified Divino as the one who shot the journalist in the head seven times. But Divino never admitted having done so. Up to a few days before the Federal Supreme Court upheld the 14-year imprisonment sentence against him on May 8, 2001, Divino was walking freely in the street.

The IAPA Rapid Response Unit in July this year talked to residents of Ceilândia, a suburb of Brasília notorious for its high level of crime. The Unit learned that Divino had been seen in previous months near his relatives' home, but the local residents declined to talk about him when his name was brought up.

Divino's defense attorney, Geraldo Côrtes, acknowledges that it was a mistake that enabled his client to disappear. "If the court wanted to apprehend him, it should not have advertised the fact. It was published in the newspapers that the court had ruled against the case presented by the defense," Côrtes said jokingly. He also defended Iracildo José de Oliveira, another defendant in the case. Iracildo died in 1999 after spending some time in prison.

Following the court ruling, Côrtes told the Rapid Response Unit that he planned to file a new injunction seeking to quash the prison sentence, just as he has been doing over the years - arguing, among other things, that his client has mental problems. "Divino became ill and never finished his law studies. He has been fighting for 17 years," the lawyer said. He is seeking a new trial, on the grounds that Divino was sentenced on a split vote by the judges - 4-3. He also maintains that the cap worn by the murderer that contained fragments of the deceased's brain matter - one of the pieces of evidence produced in the investigation - was not Divino's size. "If it were, he would be jailed immediately in any new trial," the lawyer declared.

Côrtes said the case against Public Safety Secretary Col. Lauro Melchíades Rieth and Specialist Police Coordinator detective Ary Sardella, initially suspected of being behind the murder, was dropped." The allegation speaks clearly to the fact that the colonel ordered Sardella to contact Iracildo and Divino, but there being no case of anyone masterminding the murder, neither could there be one to show who actually carried it out," he said.

The Brasília state attorney, João Alberto Ramos, was advisor to the Attorney General's Office in 1985. He was involved in the second stage of the case - he was the one who examined the accusations against Rieth and concluded that he should be ruled out as a suspect. "There was no evidence that the colonel was the instigator of the crime," Ramos said. "Of course, he did not like Mário Eugênio, but that was no secret. A lot of officials did not like him." Once it was ruled out that anyone had masterminded the murder, in the view of the Attorney General's Office, it made no sense to continue accusing Sardella of being an intermediary.

In the state attorney's view, if anyone remained unpunished it was Divino. According to him, the Criminal Procedure Law needs to be improved, because it allows arguments such as those of Divino's lawyer. Ramos was a member of the Prisons Board that heard requests for parole for two of those involved in the journalist's murder - Sergeant Nazareno and Corporal Couto. "Both of them served their sentence and fulfilled all the requirements for release for good behavior in prison," he reported.

The accusations against Public Safety Secretary Rieth began being made shortly after the murder. Senators and congressmen came out blaming him for the murder. The newspaper Correio Braziliense on November 13, 1984, published a page one story headlined "Congress accuses Rieth." Rieth's resignation was called for by members of the national Congress. He was accused of committing a crime by omission - failing to protect the journalist even though he knew he had been receiving death threats and for having months earlier ordered the confiscation of his weapon, arguing that only the military could have one. That left the journalist vulnerable to the threats.

In an interview with reporters on November 13, 1984, Rieth explained that Oliveira's gun permit had been obtained fraudulently and he added that it would have been impossible to give him police protection 24 hours a day.

A number of congressmen at the time recalled that Rieth had been implicated in the unlawful imprisonment, torture and murder of Army Sergeant Manoel Raimundo Soares in Porto Alegre, capital of Rio Grande do Sul state, in 1966. A Congressional Commission was set up to investigate the charges at that time. The "Tied Hands Case," as it came to be known, resulted in the dismissal of the then state public safety secretary. Rieth was the state police superintendent.

Correio Braziliense on November 13 reported that "Rieth came to recognize that the case of the reporter's death could be hard to solve, but he gave assurances that he was personally working on the investigation. He promised to submit his findings to the judicial authorities within 30 days." Radio reporter Roberto Cavalcanti, known as Perdigueiro (Bird Dog), currently director Radio Cultura in Brasília, believes that Rieth was one of the best public safety secretaries the Brazilian capital has ever had. "He knew everything that was going on and took action," Cavalcanti said, who himself had made a statement, when he was working for television in Brasília, in favor of Detective Ary Sardella during the investigations. "The people involved in the Oliveira murder were brought to justice, everything was investigated with the greatest possible transparency," de declared. Coincidentally, he currently hosts the radio program "Distrito Zero," aired 6:45 to 7:30 a.m., the very name given by Oliveira to his column in Correio Braziliense. Retired police officer Ivan Baptista Dias, known as Kojak, who was president of the Police Officers Association (Agepol) in 1983-87, commented that everything that happened in the police force at that time went through Rieth. "He was very much feared and because he was in the military he had good relations with fellow officers," Dias said.

Oliveira initially was good friends with Rieth. Neither colleagues nor police officers he dealt with could clearly say when that relationship began to deteriorate. Some of them believe the situation changed when Oliveira published the first exposes implicating members of the Army. According to Dias, Rieth was believed to have asked Oliveira not to publish the story. In his stories, Oliveira linked the civil police officers' low pay with the increase in crime in Brasília.

"Oliveira began to make more exposures when he discovered that police were directing gangs of thieves, said Renato Riella, former executive editor of Correio Braziliense and Oliveira's immediate boss. "He learned that a number of youths were being used by police officers and members of the Army to steal automobiles, but when they got in their way they were killed," Riella said. Oliveira discovered that there was an auto theft ring that stripped vehicles or sent them to Bolivia, sometimes returning with drugs. He also learned that the gang's base was among the members of the Brasília Auto Theft Police Unit and the Army Criminal Investigation Squad (PIC).

The murder in April 1984 of farmer João Baptista de Paula Matos in a small village near Luziânia, Goiás state, some 30 miles from Brasília, was one of the first cases that Oliveira openly reported to the police. Oliveira described PIC members and police officers from the Auto Theft Unit as murdering an innocent person while searching for an automobile belonging to an Army lieutenant that had been stolen. Among them was Army Lieutenant Ricardo de Paula Avelino, in addition to Nazareno, Iracildo, Couto, Loiola and Dirceu Perkoski (who allegedly took part in a first aborted attempt to kill Oliveira) - all of them later accused of participating in Oliveira's murder.

Correio Braziliense published a report that when Oliveira learned of the farmer's death he took the case to the public safety secretary, who threateningly told him, "It was the PIC members who killed the farmer. If you are brave enough, go ahead and publish it." Oliveira did so.

Such courageous action brought reprisals. For a time there was a police order banning Oliveira and other reporters from entering police precincts. Later, his car was confiscated on the grounds that its license tag was out of date, and then police officers went to Correio Braziliense to take away his gun.

In July 2001 the IAPA Rapid Response Unit tried to locate Rieth in Brasília, where he now lives, and after four attempts to establish telephone contact a woman who refused to identify herself said he was not interested in talking about the case.

When he testified to police on February 20, 1985, Rieth recalled that for the first 2-1/2 years of his administration he had had no problems with Oliveira. But from the moment that Oliveira began to publicly allege police involvement in various kinds of crimes the disagreements started. "If any mistakes were made," Rieth said, "they should be attributed to those really responsible." He asked Oliveira to present evidence so as to punish the guilty. Faced with the allegations published by Correio Braziliense under the headline "Derelicts executed as scapegoats," Rieth in his statement to police said he requested a right of reply.

The newspaper played a key role in the investigation into Oliveira's death. For months it devoted at least one page a day to the case. Otávio Ribeiro, a crime reporter in Rio de Janeiro and a friend of Oliveira's, was called to help in the coverage. "They put pressure on us," said Riella, one of those in charge of the reporting. He automobile was followed and he received anonymous threats.

With some of those involved in jail, Oliveira's death began to be forgotten. But there remains a climate of impunity. "The crime was not solved, they only identified who pulled the trigger. It would be solved if we could only find who ordered the murder," declared Paulo Roberto Rafael de Oliveira, 46, the dead reporter's brother.

Shortcomings in the process

Former state attorney Paulo Tavares Lemos followed the investigation into Oliveira's death from the outset and recalls the difficulties that were encountered. "It was suspected that the Office of the Public Safety Secretary was hiding information," Lemos said. "When the secretary was asked to collaborate, he always had different excuses and claimed that he had to make inquiries outside Brasília."

The fact that police officers might have approached a suspicious vehicle the night of the murder was only discovered and begun to be investigated after the change of government in March 1985. Lemos believes that if the authorities had communicated this fact earlier (they knew about it, as was proved in testimony from witnesses), the investigation could have advanced. Although he had sufficient evidence to implicate Rieth and Detective Sardella, Lemos was surprised when he learned that the Attorney General's Office asked for the case against Rieth to be dropped.

Lemos felt there were inconsistencies. Rieth's attorney filed a writ of habeas corpus to prevent criminal action for lack of evidence and for the case to be dismissed, because he held the Court of the Federal District to be incompetent to try a public safety secretary. The Federal Supreme Court rejected the plea, indicating there was evidence of the murder having been ordered. However, on the competency issue it agreed, ruling that the case sold be tried under federal jurisdiction. On this basis, the case went to the Attorney General's Office, where there was an impasse - it remaining unclear whether the attorney general now should ratify earlier accusations or not. He took a while to come to a decision and, faced with this doubt, he opted for dropping the case. Should any further evidence come to light, both Rieth and Sardella could face charges again.

Another mistake pointed out by Lemos has to do with Iracildo, one of those involved in the murder, who initially was convicted of manslaughter - a crime for he faces only a little over one year in prison. However, the Public Prosecutor's Office put Iracildo on trial again, this time for homicide, and he was sentenced on that charge to nine years' imprisonment. "These judicial mistakes ended up producing just one result," said lawyer Paulo Cesar Tolentino, a detective in the Homicide Division at the time of Oliveira's death and a friend of his.

The one positive result of the case, in the opinion of journalist Renato Riella, was the "purification" of Brasília's police department, thanks to the repercussion of the awareness of police officers' participation in Oliveira's murder.

Marão, a controversial and boisterous reporter

Mário Eugênio Rafael de Oliveira, nicknamed Marão by his friends, was for a long time Correio Braziliense's only crime reporter during a time of political transition in which Brazil - and as a result journalists - tried to shake off 30 years of dictatorship, censorship and torture and establish the basis of a democracy after military regimes had come to power in the coup d'etat of 1964.

Brasília, location of the Brazilian presidency, was not the same city it is today, having population of just 227,456. "At that time there were a lot of people from the Armed Forces working in the police precinct to obtain information," explained civil police officer Ivan (Kojak) Baptista Dias, now retired. Many members of the military had civil police or detective I.Ds. Dias was nicknamed Kojak by Oliveira himself because he looked so much like the American TV detective. Oliveira gave nicknames to a number of public figures.

In those days, crimes were given much more space in the paper and so would appear on the pages written and edited by Oliveira, recalled reporter Ana Maria Rocha, who was married to him from 1978 to 1980. The young Oliveira came to be known in the city for his combative style of reporting the news. "He was constantly threatened because he exposed the underbelly of Brasília, but he had a sense of justice. Once he was criticized for showing the human side of an outlaw, his family problems and his tough life," Ana Maria remembers.

On Radio Planalto, Oliveira was famous for his hit program "Gogó das Sete," named for its sponsor, Gogó milk. That was also why the first aborted attempt to kill Oliveira came to be known as "Operation Milk." Sometimes he would use sensationalist language in his radio program.

The detectives that he denounced attempted to sue him for libel and defamation, but he was never found guilty. "I do not defend corrupt police officers, I do not defend thieving police officers, I do not defend police officers who beat up a worker. And the place for bandits, for me, is in prison or in a cave," Correio Braziliense quoted Oliveira as declaring in one of his most popular phrases.

Oliveira's reported contained a great deal of detail, but he also dressed up the information, said Carlos Honorato, who worked at Correio Braziliense and now is executive editor of Jornal de Brasília. A number of journalists criticized Oliveira for his promiscuous relations he had established with his police sources. "He witnesses murders and tortures and that is why he wrote with so many details," said a reporter who asked not to be identified. Retired detective Tolentino said that he often went out with Oliveira at night to have a drink and added that "he even photographed a number of torture se4ssions and showed me the pictures. Oliveira wanted to get a scoop, he planned to write a book. He was compiling a dossier." Tolentino was in charge of the investigation into Oliveira's death at the Homicide Squad in Brasília. After the murder, the dossier was searched for at Oliveira's home and at the newspaper. Tolentino says the notes and photos were never found.

When Oliveira initiated his conflict with Public Safety Secretary Rieth and began publishing allegations about police officers and members of the military, Tolentino warned him that his life was in danger. "Oliveira had a St. George medallion and he always said the saint would protect him."

Although he never talked about it, Ana Maria knew that Oliveira went with police officers on their operations. She said there was a lot of prejudice at that time against reporters covering the crime beat. "He was discriminated against by those who called themselves 'leftists"," she noted. When he ran for congress as a candidate of the PDS party, regarded as rightwing, Oliveira reinforced this stigma. "But he would not get involved in political or ideological issues, he covered the police beat 100%," said Renato Riella, the former executive editor and Oliveira's boss at Correio Braziliense.

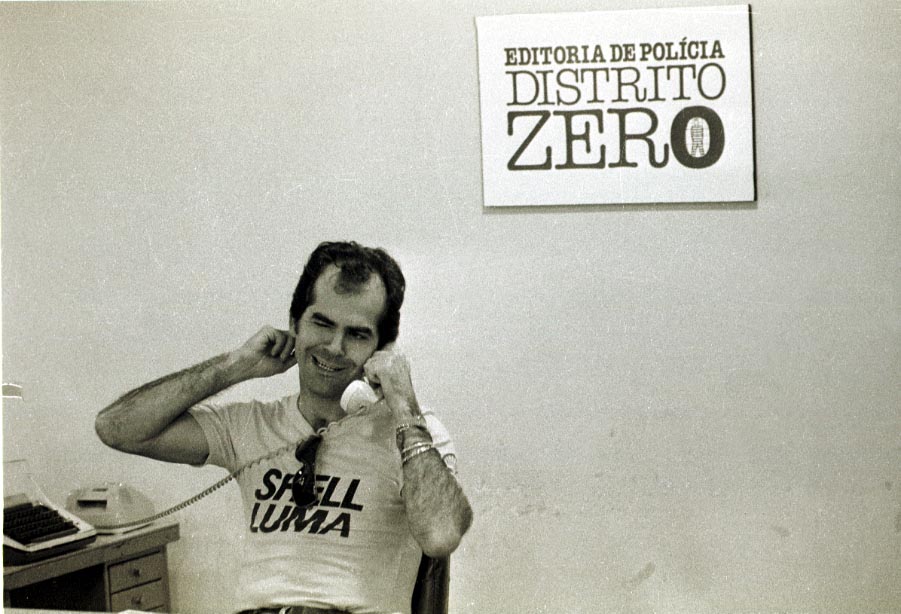

Oliveira did the whole crime page at the paper - from photos (which he sometimes took) to text to editing. Near his desk he hung a plaque saying "Police Editing Headquarters - Zero District," which turned out to be his brand. Sometimes, irritated with the drivers he would prefer to drive himself when he went to check out a story. During the week of his death he had arranged to take a vacation in December. When he came back, he and his boss Riella would draft a new work schedule, because the editor felt Oliveira was not using his time fully. The idea was he would start doing bigger, more in-depth stories.

Ana Maria is certain that if Oliveira were alive today he would be exposing corruption in government. "He would be the same competent reporter, because he breathed newspaper all the time," she declared. He initially balanced work with his hobby, motor-cycling, Some colleagues did not like his somewhat playboy lifestyle. The son of ranchers, money was no problem for him. He was good-looking and was known as a womanizer. He even had a fan club for his radio program. With an increase in work at the radio and on the newspaper, his motor-cycle outings grew fewer and fewer. Early morning, before returning home, he used to go and check that his page in the paper was all right.

As a boy, Oliveira was restless and persistent, and as an adult he had a strong character. "It was that temperament that led to his death," said his brother, Paulo. Everyone knew that Oliveira was receiving death threats. But because they were very frequent, he paid no attention to them. When Paul learned that in his notes he named powerful people, he advised him to "leave them alone." "Mário told me that if he were killed everyone would know that it was down to Lauro (Lauro Rieth)," Paulo recalled him saying.

Oliveira's mother, Maria Eres Rafael de Oliveira, 68, does not understand why they cannot identify who was responsible for planning the murder. She believes it is a shortcoming of the justice system. If at the time everybody was wanting to know who did they could not find out who ordered the crime, would it be possible that the justice system reacts now? she wondered, adding, "I place my hope only in God, because I believe you get nothing here. Nothing."

The Brazil in which Oliveira died

At the time that Oliveira died, Brazil was preparing itself to emerge from 30-year military rule. The military has seized power in 1964 in a coup d'etat. During the 1979-85 administration of Gen. João Baptista Figueiredo the process of transition to democracy began. In 1983, there were the first demonstrations calling for direct presidential elections. A bill for such elections was voted down in Congress. But the governor of Minas Gerais state, Tancredo Neves, the leader of the opposition party, formed an alliance between the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) and the Liberal Front Party (PFL) and was elected president by an Electoral College in January 1985. Tancredo became ill and died on April 21 that same year. Vice President José Sarney assumed the presidency. The return to democracy, however, became official only when the new Brazilian Constitution was promulgated in 1988, four years after Oliveira's death.

How the murder occurred

It was 11:55 p.m. on November 11, 1984. Reporter Mário Eugênio Rafael de Oliveira had finished taping his radio program "Gogó das Sete" for broadcast the following morning, Monday. He left the Radio Planalto studios, in the Southern Radio and Television Center in Brasília. When he came close to his Monza car in the parking lot, he was shot seven times in the head.

Radio engineer Francisco Resende, known as Chiquinho, who had taped the program with Oliveira, heard the shots and in the distance he saw a man wearing a hat and dark jacket and holding a gun in his hand running away. He then saw a white car take off rapidly.

The police investigation established that the shots were fired from a 12-gauge shotgun and a .38-caliber Magnum revolver owned by police officer Divino José de Matos, known as Divino 45 - ironically the nickname given to him by Oliveira himself in recognition of his being a sharpshooter. The revolver's special hollow point bullets blew out Oliveira's brains, spewing brain matter all over the floor and on the assailant's hat. Oliveira lay dead sprawled near his car.

According to the police report, Divino fled in a white vehicle driven by Army Corporal David Antônio do Couto. Nearby were other police officers who were part of the support group taking part in the crime. Observing everything from inside a Fiat car belonging to the Army Criminal Investigation Squad (PIC) were police officer Iracildo José de Oliveira and Sergeant Antônio Nazareno Mortari Vieira. They were ready to act in case of any eventuality. Another support group was made up of police officers Moacir de Assunção Loiola and Aurelino Silvino de Oliveira. The two were pretending to be there to arrest a suspected thief. They were in a black Chevette car usually used by Sergeant Nazareno.

The investigation came up with the name of Colonel Lauro Melchíades Rieth, public safety secretary of the Federal District, as suspected of having ordered the murder. According to the police report, statements by witnesses indicated Rieth was believed to have asked one of his assistants, detective Ary Sardella, head of the Specialized Police Coordination Unit (CPE), to choose who would carry out the murder. Sergeant Nazareno was made responsible for deciding who would take part in ambushing Oliveira. Both Iracildo and Divino worked under the CPE. And it was proved that all the others involved in the crime had participated in a police operation in the city of Luziânia in which a farmer was killed.

Oliveira had published reports in Correio Braziliense and has talked a number of times on his radio program "Gogó das Sete" about that incident. He used to say that the farmer was murdered by military members of the PIC with the help of Federal District civil police. He insisted that Rieth was aware of the situation and had done nothing about it. In the days before his death he reported on the use of stolen vehicles by Federal District police and their participation in what he called a death squad. Rieth acknowledged the existence of a death squad in an interview he gave 15 hours after the murder.

In October 1984, the same group has attempted to kill Oliveira. Divino, Iracildo, Nazareno, Couto, Loiola, Aurelino and Army Corporal Dirceu Perkoski went to the parking lot outside Radio Planalto, but Oliveira never turned up there. Anyway, there were too many people around at the time. Dubbed "Operation Milk" - because Oliveira's radio program was sponsored by a local dairy - the attack was postponed to November 11. In the second attempt, Corporal Perkoski was not in the group.

Statements made to the team that investigated the murder indicated that the second "Operation Milk" was organized at the home of Sergeant Nazareno on Saturday, November 10, 1984, at a barbeque with Iracildo, Couto and Aurelino. The next day, they went back to Nazareno's home on the pretext of continuing the barbecue, along with Divino and Loiola. They went from there to carry out the operation. But in order to distract attention they first went to the PIC headquarters. They pretended to be on an official mission in which Nazareno and his subordinates would conduct a campaign to arrest suspected muggers in a local square. In fact, from there they could stake out the Correio Braziliense building and see when Oliveira came out and made is way to the radio station.

An unexpected thing almost spoiled the plans and turned out to be decisive in unraveling the crime. As Nazareno and his group were pretending to be carrying out their clampdown, a team from the Special Operations Group (GOE) making its rounds thought the presence of four men in caps sitting in a black Chevette was strange, given that the place was usually only frequented by lovers. The three GOE officers approached the car and recognized Iracildo. As he was "one of them," they moved on. To avoid suspicion, Nazareno radioed for a backup vehicle, which was assigned to Loiola. Nazareno went in the new car, a Fiat, to the place where Oliveira was to be murdered to back up the police officers already there. The Chevette remained at the square.

Statements by those involved confirmed that it was Divino who fired the shots at Oliveira and that he washed the cap and wig used in the crime as soon as he arrived at the PIC headquarters. Nazareno had the revolver dismantled and the pieces thrown in Lake Paranoá. The wig, cap and other objects were hidden in a shed.

It was clear from the investigation that when they learned of Oliveira's death the GOE officer that had seen Iracildo and other police officers in the car parked in the square they suspected that was linked to the crime and they relayed their suspicion to their boss, detective Ângelo Neto. He in turn informed detective Benedito Gonçalves and Public Safety Secretary Lauro Rieth. The officers were ordered not to speak to anyone about the presence of Iracildo and the other police officers that night near the place where Oliveira was murdered.

The fact, however, came to the knowledge of reporters covering the case for Correio Braziliense. The newspaper received anonymous telephoned and written tips almost every day. Police officer friends of Oliveira also were ready to help. The confirmation that Rieth was informed of the presence of a group of police officers in the square on the night of the murder but had failed to take any action was grounds for the state attorney accusing him of being a suspect in the crime.

Who is going to accuse the instigators?

In July 2001, the IAPA Rapid Response Unit interviewed one of the participants in the operation in which Oliveira was murdered. Having served his prison term, he is living today with his family in a rural town in Brazil. Pleasant, although apprehensive, he talked for nearly two hours at his home. He did not want his name to be disclosed because he still fears reprisals, although he did tell his version of events.

"We were all very young, about 20. And that was a time when to be a member of the military gave you status. If it were today, I wouldn't be involved. It isn't that I could have stopped Oliveira being killed, but perhaps I wouldn't have been in that group. Just five minutes before the murder I was certain they were going to kill him. In the first 'Operation Milk' I thought they were only going to arrest him.

"The motive for Oliveira's death was not the allegations he made about the mistaken murder of the farmer. We were sure that nothing was going to happen to us as a result of that crime, because there was a hierarchy and the story was going to end higher up. We only realized that we had killed the wrong person a week or two later, but the detective in charge of investigating the crime gave us the bullets that had been encrusted in the walls. Loiola (Moacir de Assuncão Loiola, who took part in the killing of the farmer and of Oliveira) committed suicide, because he was the weakest one.

"There was an interest in eliminating Oliveira. But who, even today, wants to get mixed up with a detective like Ary Sardella? Colonel Rieth perhaps knew everything. Who is going to accuse him? I don't want to talk about who might have ordered it. I have children, I don't want to involve my family any more, they've suffered enough.

"Divino 45 (Divino José de Matos) is out free because he is the only one who denied taking part. The lawyer told me that if I had denied it, perhaps I too wouldn't have gone to prison, because if a person does not admit guilt, a doubt always remains. But I preferred to talk. Divino is not going to be jailed because he was people that protect him. Police officers older than 30 are not going to want to arrest him. He is the one who could talk about who ordered the murder. He and Iracildo (who is dead).

"Oliveira went along on many police operations, like other reporters at that time. When he died, others took his place at the radio."

|