March 21, 2005

Case: Zaqueu de Oliveira

|

The day of the murder, Oliveira was up at 5 a.m. to distribute his newspaper:

November 1, 1999

Ana Arana

Quaint as a picture postcard of turn-of-the-century Brazil, Barroso is a town where men go by nicknames like Timonel or Buey (steer) and out-of-towners are considered foreigners.

Daily life in this community of 10,000 centers on the intense activity of a large cement factory, a bustling dairy industry, a conservative church and a small group of political families who take turns running things. These families may react violently when targeted for political criticism, according to local residents.

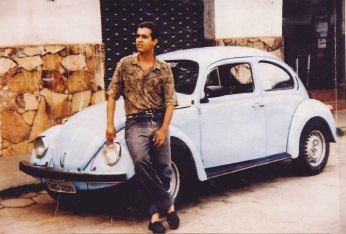

Barroso boasts of being peaceful and concerned about the welfare of its residents. Its crime rate is low, the residents are law-abiding and the church is at the heart of the community. But Barroso is also a place where intolerance can lead to disputes, duels or so-called crimes of honor. That’s what happened to Zaqueu de Oliveira, a handsome 28-year-old who was murdered March 21, 1995.

Publisher of Gazeta de Barroso, Oliveira often criticized the church and the lowly passions of local politicians in his newspaper.

Oliveira settled in Barroso in 1992 and thus was considered by many in the town as an outsider, a “foreigner.” Soon after settling in, he decided that what Barroso needed was a newspaper to keep the local politicians in line.

“The Truth Hurts Anyone,” was his newspaper’s slogan. “The paper gained wide acceptance among the people nobody paid attention to,” according to Cristiano Rodrigues Pereira, who wrote a column for the paper.

Oliveira wrote about health problems, bad roads and occasionally such “lost causes” as the local Protestant church’s request for permission to place a plaque of thanks to the city in the main square. The local Roman Catholic church protested and convinced politicians that the plaque would directly affront all the town’s Catholics. Oliveira also campaigned to close down the local old folks home, run by the Catholic Church, after one of the home’s residents killed another.

The Crime

Oliveira, the son of a retired army sergeant, decided to settle in Barroso and marry Gislene Silveira, 24-year-old daughter of one of the town’s most prominent families. The wedding was set for June 1995. Oliveira was of medium stature and had big brown eyes and bushy eyebrows. “He was smart and nearly perfect,” recalled Silveira sadly. A slightly-built woman with brown hair, she still refuses to walk alone around town.

“She’s still grieving. She cries a lot. After her fiancé’s murder, she locked herself in her bedroom for four months,” explained Rodrigues Pereira, who has a day job as a car mechanic and now publishes a newspaper he started after Oliveira’s death.

The day of the murder, Oliveira was up at 5 a.m. to distribute his newspaper.

A story published in that edition apparently led to his murder. In the story, he made fun of the mayor’s secretary.

“Hysterical secretary and incompetent mayor disrespect student’s mother,” read the front-page teaser. The article, printed on page seven, said the allegedly aggrieved mother and daughter were not identified for their protection. “Mrs.E.G.O., 44, mother of the student R.O., 21, both Barroso residents, have been victims of the manipulation of the monster of the pit who occupies the office of the incompetent mayor of Barroso and his hysterical secretary, Ana Lúcia do Valle,” the article said.

A sidebar described the lengths the mayor would go to force people to call him “excellency.” What Oliveira did not include in his story was that the two affronted women were his own mother and sister. This relationship apparently added to the slant of the story.

Oliveira’s articles offended the town’s top bourgeoisie families, according to Rodrigues Pereira. “This town is run by a small group of rich people,” he said.

A Duel or a Murder

Ana Lúcia do Valle, the mayor’s secretary, was married to the local butcher, José Carlos de Souza, a foul-tempered large man who was a perfect marksman and a gun collector. His shop faced the town square. He had political connections and the mayor was his cousin, according to town residents.

De Souza, known as Zédo Tatão, learned the night before Oliveira’s murder that the next edition of the Gazeta de Barroso would run an article critical of his wife. The following morning, de Souza and his brother circled the journalist’s house in an effort to harass and intimidate, according to testimony from the Oliveira family in court records.

Several of Oliveira’s friends advised him not to distribute the daily. But the journalist had his mind set and took copies of the paper to all the usual places. To protect himself he carried a handgun he’d bought a few months earlier as a precaution. According to his mother’s court testimony, Oliveira had received several death threats because of his articles. Oliveira had the revolver -a Brazilian-made Rossi .38 caliber -tucked into his waistband that morning as he rode a motorcycle with his mother.

“My father told him to be careful,” said his fiancée, Gislene. “But he thought the gun would scare people away.”

What happened next is difficult to clarify, because witnesses have contradicted each other. According to relatives and friends of Oliveira, several people were pressured by the de Souza family to testify in their favor. The morning of the crime the square was full of people, but nobody remembers who shot first.

Some believe that Oliveira was shot when he tried to defend himself from de Souza’s better marksmanship. “Zaqueu (Oliveira) didn’t know how to shoot. He carried the gun to keep others from attacking him, but I knew he couldn’t shoot,” said the fiancée.

Erondina das Graças de Oliveira, the journalist’s mother, gave police a chilling account of the murder. She said Oliveira was driving downtown on his red Yamaha motorcycle and arrived at Santana plaza around 10:50 a.m. Mrs. Oliveira said she wanted to call her daughter from the telephone office located near the plaza. As they arrived at the plaza, the account continued, de Souza approached carrying a gun and a big knife.

“I would have preferred meeting some place else, but it will have to be here,” de Souza told her son, according to Mrs. Oliveira. De Souza then hit her son in the face, knocking him to the ground. Oliveira tried to stand and run, but de Souza started shooting. When Mrs.Oliveira tried to protect her son by stepping between him and the attacker, she testified, de Souza, shot her in the left hand and the stomach.

De Souza told the police that he was offended by the newspaper article that called his wife “hysterical and slow witted.” He said that his intention was to approach Oliveira politely to demand a retraction.

De Souza’s mother said Oliveira struck first, hitting her son in the face, and then started to shoot. She said de Souza fired only in self-defense. She could not recall if Oliveira’s mother had been assaulted during the fracas.

One witness who worked in the mayor’s office corroborated de Souza’s version and even added a new detail to the investigation. According to this witness, Brasilino de Melo Neto, the mother provoked the attack by encouraging Oliveira to shoot at de Souza when he first saw him in the plaza. “Shoot, shoot,” the witness quoted Mrs. Oliveira as saying in his court testimony.

An examination of the court testimony given by more than a dozen witnesses, including six who were near the town square at the time of the murder, confirms that certain elements are true.

Oliveira died trying to defend himself, taking shelter behind a tree. His mother, apparently frightened by what might happen, urged him to shoot in self-defense. Many witnesses said they could not remember who shot first, but friends of Oliveira admit being afraid to accuse de Souza directly.

Oliveira was killed by a .32-caliber bullet, the same as used by de Souza’s gun. His mother was seriously injured in the hand and stomach by bullets of the same caliber. Unhurt in the volley of gunfire was de Souza, who fled in his car after the killing and later turned himself in at the police station.

The investigation

The investigation was tainted from the beginning by the political influence of de Souza’s family, relatives and colleagues of the journalist said. The case was moved to Barbacena, a city located a half-hour drive from Barroso. A local judge and prosecutor there conducted the investigation and trial. By the time the IAPA requested access to the court files, it had been decided summarily to absolve de Souza of all charges on grounds that he had acted in self-defense. Legal sources consulted in Barbacena said that an examination of the evidence and court testimony did not support the prosecution’s decision.

Oliveira’s family intervened cautiously as the investigation began, but then faded as it became clear the family had no influence over the process and progress seemed to be favorable. “I heard nothing from his family in the last year,” said Silveira, Oliveira’s fiancée, who still lives in Barroso with her family.

Oliveira and His Enemies

“He was a yellow journalist...who had a clandestine newspaper,” said prosecutor Dilma Jane Couto Carneiro Santos, when asked about Oliveira’s murder. Carneiro Santos, a short, heavy-set woman in her forties, said Oliveira had attacked many people in the town of Barroso and had many enemies. “De Souza shot at Oliveira only after Oliveira shot at him first,” she said.

However, an examination of testimony in the case does not favor Carneiro Santos’ position. Neither does the police investigator who headed the inquiry until his retirement early in 1998.

Unexpected hostility greeted an IAPA visit to the Pimentel court records office in Barbacena. Several court employees were openly biased against Oliveira and his work as a journalist. This attitude was curious given that Oliveira had never written anything about Barbacena in the Gazeta de Barroso.

When IAPA investigators were reviewing court documents, friends of de Souza approached the woman in charge to ask about the visitors. “I’ll be happy when this is all over and he is acquitted,” one woman was heard to say. The IAPA could not determine if the de Souza family had relatives, friends or associates working in the Barbacena court. It did learn that the wife of de Souza’s lawyer, Francisco José Reis Fortes, is a court employee.

Influential Politicians

Reis Fortes, tall and corpulent, received IAPA at his office. Asked if any relatives of de Souza worked for the courts, he said he did not know. Seeking to impress his visitors, he made a call in their presence to the de Souza home in Barroso and asked the person answering if any family member worked for the courts. “No, no one,” he said to the IAPA investigators. Then he talked into the telephone again: “Yes, we will offer a Mass of thanks when this is all resolved,” he said.

Reis Fortes told the IAPA that he was well-connected with influential politicians in Belo Horizonte, capital of Minas Gerais state. Oliveira was publishing a clandestine newspaper. "He liked to provoke people,” he said, repeating comments already heard by the IAPA.

The lawyer said the court would also indict Oliveira’s mother because it was believed that she provoked the attack by urging her son to shoot at de Souza. His accusations are serious, considering that the journalist’s mother was gravely injured by de Souza during the incident. Nevertheless, the lawyer feels confident the law is on his side. “It will be hard to send this case to a jury. The judge will acquit my client,” he said.

A case everybody wants to forget

Father Fabio José Damasceno is in his early 30s and has the face of a cherub. Short and plump, he’s been Barroso’s priest for the last three years. “I did not know Zaqueu, but I’d heard he had problems with everybody,” he told the IAPA visitors in his residence.

As the conversation warmed up, he provided more details. “Well, we did have some problems. Oliveira called for the closing of the old folks home the church kept going at great pains,” he said. “He started a scandalous campaign saying that the church should not manage the home.You can imagine our distress,” the priest said, gesturing with his hands.

Oliveira’s fight with the church was the last straw that led to his murder, his friends commented.

The priest “detested” Zaqueu (Oliveira), Silveira said. “When he wrote editorials against the church’s management of the home, the priest devoted his entire Sunday sermon to attacking Zaqueu and his newspaper,” she added.

The journalist also angered the church by endorsing a Protestant proposal to place a plaque in the main square thanking the city of Barroso. Father Damasceno was vehemently opposed to the idea. Oliveira called the priest a “military dictator.”

“De Souza is a good man,”the priest declared at the end of the IAPA interview.

“Oliveira created his own problems.”

Conclusions

Several town residents believe that Oliveira misinterpreted Barroso’s political climate. “This town is very corrupt and the local parties are linked to major political parties in Minas Gerais,” Silveira explained. “My father warned him about the political climate in this town, but he paid no attention,” she added.

“Zaqueu was very smart, but he never imagined that anything serious could happen,” said his friend, Rodrigues Pereira during an IAPA interview at his modest home in Barroso, where he has an extensive book collection. Holding up a copy of the newspaper he launched after Oliveira’s death, he said reflectively, “I’m more careful. The fear we all feel became more real when we saw Zaqueu in the coffin.”

Rodrigues Pereira continued: “Zaqueu took on anybody. His newspaper represented this town’s poor, people who were ignored by the politicians. But neither of us expected these consequences. Now I understand that we are alone.”

As of May 1999, the Oliveira case was working its way through the First Criminal Court of Barbacena, the town close to Barroso. In June 1998, prosecutor Carneiro Santos requested the summary dismissal of charges against de Souza on the grounds of “legitimate self-defense.” Carneiro Santos is an associate in the state’s public ministry, the institution responsible for applying Brazil’s laws in the judicial system. According to her, de Souza did not fire against Oliveira but only defended himself from the shots fired by the journalist. De Souza actions were justified, she said, because Oliveira “had offended the honor of a married woman, provoking the anger of the merchant (de Souza).”

Disagreement

Judge Mariza de Melo Porto, presiding in the Oliveira case in Barbacena, disagrees with the prosecutor’s opinion. Melo Porto perceives criminal action in de Souza’s behavior. She decided he should go to trial before a jury. She explains that the investigation does not clearly prove that de Souza acted in self-defense and society; therefore, must judge the crime he allegedly committed.

Reis Fortes, de Souza’s attorney, presented an appeal in December 1998 in the Minas Gerais second circuit court of appeals. He argued against Judge Melo Porto’s decision to bring de Souza to jury trial. He reaffirms the validity of the summary dismissal on grounds that the accused acted in self-defense. Before making the appeal, the defense lawyer illegally kept the case file in his home for nearly four months. He returned these documents only under a search and capture order from the court. Detaining the case file is an illegal maneuver intended to delay criminal proceedings, something that is quite common in Brazil. Brazilian law dictates that the case files be sent to the attorney general’s office, a branch of the state’s public ministry of first appeal, for a new opinion.

After the Brazilian summer holiday extending from the end of December till the end of January, prosecutor Ruth Scholt Lies ruled in February 1999 against the appeal presented by de Souza’s lawyer before the state’s justice tribunal. She returned the case file to a three-judge panel who must decide, finally, on the petition of the man accused of murdering Oliveira.

The three judges of the Third Criminal Court of the Justice Tribunal in Belo Horizonte decided to challenge de Souza’s appeal and order judicial authorities in Barbacena to set a date for a jury trial. De Souza would be tried for the murder of the journalist and the attempted murder of the journalist’s mother. The panel’s ruling confirmed the earlier judgment of Judge Melo Porto.

Once the bureaucratic requirements were met, the proceedings returned to Barbacena, juridical seat for Barroso, where the trial date was to be set. At the request of Maria Clara Prates Santos, an Estado de Minas newspaper reporter who is following the case closely, the presiding judge of the Justice Tribunal continued the case until September 1999.

Brazil’s legislation has been criticized for allowing several defense “appeals ” in this case and for excessive formality which has been tantamount to granting impunity. Also criticized has been the fact that the accused remains free four years af ter the murder of Oliveira.

Following attention focused on the case by the IAPA and Brazil’s National Association of Newspapers (ANJ), backed by Estado de Minas, proceedings have speeded up perceptibly.

|