August 29, 1995

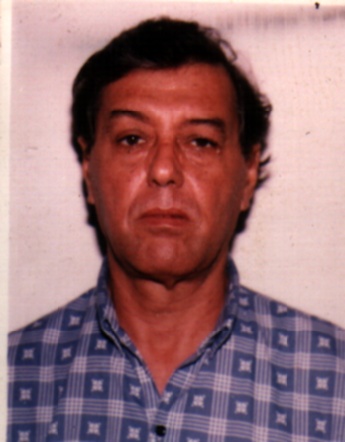

Case: Reinaldo Coutinho da Silva

|

Publisher of Cachoeiras Jornal, Cachoeiras de Macacu, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil:

September 1, 2000

Clarinha Glock

Five years after the murder of journalist Reinaldo Coutinho da Silva, publisher of the Cachoeiras Jornal, based in Cachoeiras de Macacu, Rio de Janeiro state – a case that has been made a "priority" of the Rio de Janeiro state police – the guilty have yet to be brought to justice. Eye-witnesses have disappeared and one of the people suspected of a cover-up, who was jailed for another crime, is now free. In August this year, after being asked about the findings of an IAPA inquiry and a report in the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Globo, the authorities decided to resume their investigations. The Rio Association Against Crime, a non-governmental organization, and the Rio de Janeiro state government have jointly offered a 2,000 reais (about $1,000) reward for information about the murder.

Fourteen shots were fired at Coutinho da Silva when he stopped his car at a red light on Edson Avenue in the Lindo Parque neighborhood of São Gonçalo. It was around 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday, August 29, 1995. His Gol automobile was at an intersection where a fruit and vegetable store was located on one corner, a car wash and a school on another and across the street a church.

Statements taken by the police are contradictory. One version is that there were three murderers, riding a motorcycle and driving a gray Gol car. The car had come alongside Coutinho da Silva’s Gol, or stopped behind it, and the passenger was said to have fatally shot Coutinho da Silva. Other eye-witnesses said that the assailants’ car was a black Fiat. At least two people later gave friends of Coutinho da Silva’s family details of the vehicles and the suspects. One of these people worked in a paint store on Edson avenue, since closed down. The eye-witness lived in Papucaia, on the outskirts of Cachoeiras de Macacu, some 20 miles from São Gonçalo. After being contacted by friends and family of the deceased, the eye-witnesses disappeared from the area.

Coutinho da Silva seems to be aware that something was going to happen to him. He did not speak about threats. "He was very discreet, he did not like to worry his friends," recalls Silvio Martins Paixão, president of the Rio de Janeiro State Professional Journalists Union, who worked with Coutinho da Silva at the O Fluminense newspaper. Some days before his murder, Coutinho da Silva told his family that he had seen a pick-up truck parked for hours outside his home in São Gonçalo.

Coutinho da Silva lived on a hard-to-get-to narrow street. Suspicious, he called the police. Before it got to the house, the patrol car sounded its siren and alerted by the noise, the driver of the pick-up made off and was not caught. Coutinho da Silva’s family were surprised to find that his phone call about the pick-up had not been registered in the police blotter.

On the afternoon prior to the murder a neighbor recalls having been asked by a well-dressed, gray-haired man about Coutinho da Silva’s address. According to the neighbor, the man already knew where the house was, but he wanted to know if the street had only one narrow way out. The man was driving a Gol car.

On the day of his murder, Coutinho da Silva was on his way to a meeting of the São Gonçalo Research, Study and Development Institute (Ipedesg), which he had founded with other members of the community with the aim of discussing and resolving problems in the city. Ironically, that day State Security Secretary Nilton Cerqueira was going to address the meeting about violence.

José Fernando Beliche, chief of the 72nd police precinct in São Gonçalo, who was on duty at the time of the murder, came up with a number of theories. One of them concerned documents found in Coutinho da Silva’s car on the day of his death, among them copies of a civil suit demanding closure of a lot owned by Serafim Gomes, brother of former mayor Rui Coelho Gomes, in an environmental preserve in the Boca do Mato area of Cachoeiras de Macacu.

The police officer’s second theory involved photographer Fábio Barroso, one of Coutinho da Silva’s partners at the Cachoeiras Jornal. He was a suspect because of a disagreement that had arisen at the newspaper over invoicing. According to Coutinho da Silva’s family, he had hired an auditor to look into the finances, fearing money was being siphoned off. Barroso denied to the IAPA that there had been any quarrel between the two other than the usual discussions that took place prior each edition of the newspaper.

"My family is from Cachoeiras and we work together at O Fluminense. That is why whenever Reinaldo need a photograph taken he would call me," Barroso said. He recounted how on the day of the murder he was in Rio de Janeiro, on a shopping trip with his wife. "Reinaldo was like a father to me, I learned a lot from him," he said.

Barroso had a 10% stake in the newspaper. Another 30% was held by Sueli Coutinho, who owned real estate next-door to Cachoeiras Jornal and at Coutinho da Silva’s insistence had joined the group from the outset. In 1995, Sueli returned after a two-year stay in the United States. Fearful, he said he wanted to get out of the newspaper.

Coutinho da Silva’s family sold off their father’s shareholding in the paper. Barroso kept the staff but then launched his own newspaper, which is still in operation today, at another location. He changed the name to Jornal Cachoeiras.

Another police theory concerned a dispute between Coutinho da Silva and Rogério Mesquita, owner of the newspaper Atualidades, over their competition for placement of notices of court rulings and advertising the Cachaoeiras de Macacu municipal government. According to Reinaldo’s son Mauro Ricardo the advertising was published in Cachoeiras Jornal because the city had no official gazette. When the local administration changed, the advertising went to Atualidades, without being put out to public bid. Coutinho da Silva field a civil lawsuit against the municipality in a bid to get the advertising back, and his claim was upheld.

The police have yet to investigate indications from people who lived with the suspect and the victim that Mesquita might have had some relationship with the local illicit numbers game operator, known as o bicheiro, Waldenir Paes Garcia, a.k.a. Maninho. He had a criminal record for involvement in organized crime and other unlawful activity. According to findings by the State Attorney’s Office, Maninho owns horse ranches in the Cachoeiras de Macacu area. A report published in the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Globo named him as O Bicheiro’s protector. The IAPA was unable to locate Mesquita to interview him.

Several witnesses stated that on at least two occasions – once in the Cachoeiras Jornal newsroom and the other time at a local horse fair – certain people linked to Mesquita had threatened Coutinho da Silva. In addition to the fight over official advertising, there was another dispute. Coutinho da Silva had published in his newspaper statements opposing independence for Papucaia, a Cachoeiras de Macacu district, which Mesquita favored. "If Papucaia de-incorporates, this will become another Colombia," Coutinho da Silva told a friend, in reference to arms and drugs trafficking that he thought was going on locally. In his Atualidades newspaper, Mesquita brought the issue out into the open.

"Reinaldo did not rise to the bait," former partner Sueli said. "He was very ethical and he knew how to deal with these things."

There is also the suspicion that Coutinho da Silva’s murder might be linked to the jailing in Cachoeiras de Macacu of civilian and military police officers on charges of belonging to organized crime gangs. The names and photographs of the accused were published on page one of the Cachoeiras Jornal on August 18, 1995.

The few leads there were on the suspects one by one went cold. On March 8, 1996, Military Police Private José da Silva Filho, who lived in the Japuíba district of Cachoeiras de Macacu, was arrested while driving a metallic gray Gol car with false license plates. Police searched his home, based on an accusation that he had something to do with Coutinho da Silva’s murder. He was sentenced to four years and six months’ imprisonment for theft, he appealed and the sentence was reduced to two years. He was freed in September 1998. There was never any proof that he had participated in Coutinho da Silva’s murder.

It was unofficially rumored that a drunk once had said in a bakery in Japuíba that Silva had killed a journalist. Madelon Pino da Silva, who at the time of the murder was Silva’s wife, said she knew noting about such rumors, even though she had been identified as the drunk who "spilled the beans" at the bakery. "He had no motive to kill him. Anyway, on the day of the murder he was at home with me," she said – contradicting a witness who claimed to have seen Silva arrive home around 11:30 a.m.

Although she says she is separated from Silva, Madelon called him from a public phone box outside where she works in Cachoeiras de Macacu and put him in touch with the IAPA. Silva said he did not want to give any interview and that nothing had been proved against him. He had already suffered, he said, and asked to be left alone.

The investigation into Coutinho da Silva’s death was practically forgotten until August this year. "The inquiries were not badly handled, but they were very slow," admits Milton Roberto Olivier de Azevedo, from the Rio de Janeiro Department of State for Public Safety’s Internal Affairs Oversight Office, which carries out a watchdog role over police officers’ conduct. "The police have no interest in protecting criminals," Azevedo said. "There were problems of lack of resources. Besides, that crime is difficult to solve because people are afraid to talk."

According to the head of the Homicide Division in charge of the investigation, Paulo Passos Silva Filho, who took on the job in January 2000, findings were sent in January to the Fourth Criminal Court of São Gonçalo for the state attorney’s office to be made aware of them. Only on August 25 this year were they returned to him. "We are going to follow up," he promised.

The same pledge had been made in October 1995, when the then chief of the Rio de Janeiro Civil Police, Hélio Luz, currently a state congressman, named Detective Inspector Jamil Warwar to head a Special Investigation Unit set up with the aim of investigating major crimes. One of the cases regarded as ‘a priority" at the time was the Coutinho da Silva murder.

Luz was surprised to learn that the crime remained unsolved. "The big problem is the structure in Brazil which, while it may have police to perform a social function, has no funds to investigate homicides," he said.

The congressman, who spent 10 years in the Homicide Division, believes that solving these crimes would be a way of ending others – "the illicit numbers games, drug trafficking, everything that murder ensures can go on." Luz thinks that the investigation into Coutinho da Silva’s murder could run up against people involved in the numbers game and local political interests. "If you took an X-ray of the Cachoeiras de Macacu region you would see that the numbers game is not out on the street but those involved in it own horse ranches and moreover the state fairs are funded by them," he said.

Inquiries conducted in a number of states around Brazil show that the numbers game, known as the jogo do bicho, is linked to money laundering and trafficking in drugs and arms. In cases such as the Coutinho da Silva murder, local police do not respond, Luz charged. "Whenever a homicide is investigated, it has to be done from the outside, at state level, because the pressure is very strong," he added.

São Gonçalo, where Coutinho da Silva lives, is Rio de Janeiro state’s second most populated city. The last census put the population at 800,000 but today is likely to be nearly 1.2 million. Only 11 miles separate the Rio de Janeiro state capital and São Gonçalo, a suburb of it.

Buildings whose walls are covered in graffiti, smoke and the constant noise of buses are the main features of the city. For a long time regarded as a dormitory town, São Gonçalo lives from commerce and industry, being the fifth largest tax base in the state. But the economic development has not kept pace with the population explosion. Murders in the area, according to figures from the Homicide Division, generally are the product of gang warfare linked to drug trafficking, turf wars and drug deals gone bad.

Cachoeiras de Macacu, the city where Coutinho da Silva’s newspaper was located, is in the Baixada Litorânea (Lower Coastal) region, 12 miles from São Gonçalo. Cachoeiras de Macacu state attorney Paul Sérgio Rangel de Nascimento believes the journalist’s death was plotted in that city. The fact he was killed outside it could have be intended to throw police off the trail or to escape Nascimento’s clutches. He was responsible for breaking up a gang of civilian and military police operating in the area who were jailed. As for the theory that they might have been involved in Coutinho da Silva’s murder, Nascimento does not believe it. "The newspapers O Globo and O Dia also published the photographs and the story. The fight would not have been with Coutinho da Silva, but with me and the judge," he said.

Other crimes have occurred in Cachoeiras de Macacu without the guilty being brought to trial. Coutinho da Silva spoke out against such impunity in his paper prior to his death.

Since Coutinho da Silva’s murder, his children have received threats. Fearing that something could happen to his family, José Ronaldo moved to another state. At the time of the murder he was handling the Cachoeiras Jornal’s layout and design and helping his father with marketing. "I don’t believe in the institutions any more, I just want to get out of Brazil," he said.

He added that he intends to sue the manufacturers of the bullets that killed his father as a way of calling attention to violence. "I don’t want them to find a scapegoat, I want justice," he declared.

Admired for His Abilities and His Determination

Reinaldo Coutinho da Silva was a voracious reader, he loved the classics and books about history. And he wrote forceful, critical pieces that he published in his newspaper. He also wrote poetry full of sensitivity and emotion. He liked politics and was a great innovator of social projects. Because of his dreams of changing society he founded the São Gonçalo Research, Study and Development Institute (Ipedesg), a non-governmental organization, whose aim was to bring members of the community together to discuss problems in the city and how to solve them.

He was an active member of the Nova Estrela do Oriente (New Star of the East) Masonic Lodge in São Gonçalo, having reached the rank of "venerable" (grand master). "He always defended the weak and advocated democracy," says retired military officer José Roberto Boechat, current lodge grand master.

His curiosity about history made him an expert on the life of São Gonçalo. He planned to make an oral archive of the city’s leading citizens. After launching his newspaper in Cachoeiras de Macacu he carried on writing for Nosso Jornal in São Gonçalo, thus remaining active in city life.

A gregarious person, in the evenings after work he liked to go and have a drink with friends and practice what he was best at – chatting with people from all walks of life.

He planned to make Cachoeiras Jornal a source of reference about the area. He had bought a plot of land where he intended to install a print shop. His single-mindedness was evident from the first edition of the newspaper, when he would go out and make deliveries himself. His efforts were not in vain. When the weekly Cachoeiras Jornal appeared on the newsstands, they quickly sold out.

Of his three children, the one who followed mostly closely in his footsteps was Carlos Rogério, who was studying at the local journalism school and was doing translations for a magazine. But, to Reinaldo’s sadness, Carlos died in a car crash in 1986 at the age of 21 with his mother, Maria Gilda Henriques de Silva. They were crushed by a bus. The tragedy upset him enormously and led him to write in O Fluminense: "We therefore without fear want to denounce and express distrust of a system that allows the movement of buses lacking even minimal safety conditions that travel full of passengers, as is the case of the bus company involved in this accident; to denounce the complicity of the authorities that allow the use of retired people and members of the military reserves to drive buses; to denounce the foot-dragging of the legal system; to denounce the transportation Mafia that makes money from risking passengers’ lives in exchange for favors and kickbacks from unscrupulous businessmen."

Friends who worked with him remember him as a serious and competent professional. José Fernando Oliveira Vaqueiro, the owner of a print plant, was a member of the administration of Mayor Jaime Campos in São Gonçalo when Coutinho da Silva became secretary of information and tourism. The two later together founded the newspaper O São Gonçalo.

"He managed to get close to everyone, he knew how to listen," Vaqueiro said. "He had an enormous ability to synthesize," recalls São Gonçalo’s current secretary of trade and industry, Aurenildo Brito de Azevedo, co-founder with Coutinho da Silva of the São Gonçalo Research, Study and Development Institute. And above all he had an unmatched patience to show others what he liked most – to write and publish a newspaper.

"An opportunity not taken become a difficulty," he used to tell his cub reporters, such as Adriana Vieira. "Reinaldo was fantastic, he taught us a lot, but he had a lot of other work to do," says Adriana, who still works at the paper. It was he who convinced then supermarket manager Erikson Fonseca de Miranda, to write a sport column and ended up turning him into a photographer and copy editor.

"Reinaldo used to say that he had come to give Cachaeiras a voice," declares Fonseca de Miranda, now owner of his own newspaper. He was in charge of photographing the police officers accused of belonging to organized crime gangs now in jail in Cachoeiras de Macacu.

Marilda da Silva Henriques, Coutinho da Silva’s companion in the last years of his life, recalls that he was a very sensitive person and that he always said, "They can kill me, but my newspaper is all about truth. The only thing I fear is that they burn it down and having to start all over."

Reinaldo’s Voice

In his articles, Reinaldo Coutinho da Silva used to repudiate the very violence of which he ironically became a victim. One of his last pieces, published in the newspaper Nosso Jornal in São Gonçalo which ran from August 256 through September 1, 1995, was titled "The Good and the Bad of the Police."

It said, "…the most serious public safety problem is the garbage swept under the carpet , including economic, social and educational questions. The police, due to their repressive actions, have never had a good image among the people, because there is – and always will be – someone who rightly or wrongly will claim rights imposed by law or by ill-used methods and postures. To build a good image is therefore a technically secondary question.

"The brilliance of this varnish could have another hue if the governments were to comply faithfully with their political duty to guarantee citizens the right to safety. And in addition to provide technical, educational and material resources to those institutions entrusted with maintaining law and order. On the contrary, for many years they allowed the creation of a cronyism that in many cases put political merit above real qualifications….

"If the police is not well trained, fails in its duty and is corrupt, how then to separate the wheat from the chaff? How to get rid of the police dregs, leaving society at their mercy, without a mechanism for control and defense? How to build and equip institutions prior to a general clean-up and formulation of an efficient public safety program? What can one do?

"These are questions about society that require answers. And for this what is needed is the courage to report, and to allow the reporting – without censorship – of the bad side of the Military Police and the Civilian Police."

|