October 29, 1997

Case: Edgar Lopes de Faria

|

Comentarista de Radio Capital FM y presentador de televisión en Red Record:

July 1, 2000

Clarinha Glock

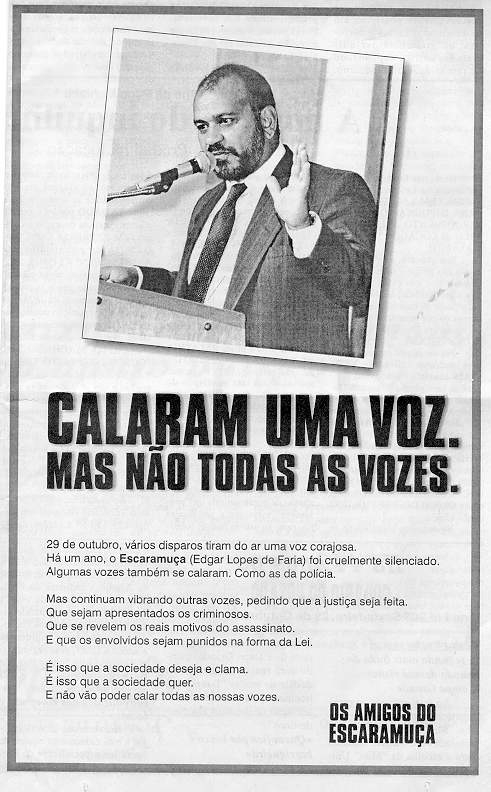

Escaramuça is Portuguese for "skirmish." In Campo Grande, capital of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, it was synonymous with Edgar Lopes de Faria. The radio talk show host and television presenter, known by that nickname, lived up to his title. In his radio talks he would raise his voice to criticize and level allegations. "That voice will not be silenced," said the radio program opening announcement .

On October 29, 1997, Escaramuça, 48, was murdered in downtown Campo Grande, shot six times. More than two years later, the police have still to identify his murderers and those behind the crime and see the case as a difficult one to solve. Eye-witnesses, fearing reprisals, are unwilling to talk about the crime.

The Mato Grosso do Sul state Civil Police chief, Milton Watanabe, told the IAPA that the case is not closed. "It is not solved," he said. "At the time, there were so many suspects that this complicated the investigation, but if a new lead emerges, we will follow it up." The main difficulty, Watanabe said, is that Escaramuça’s show was very contentious. "There is no way to ask for the case to be shelved. Solving the crime is a matter of honor for the Civil Police and whatever turns up will be investigated," he assured.

Despite the apparent good will on the part of the police, Escaramuça continues to be just a controversial memory in the city. He was a constant presence that ended on the morning of that October 29. As usual, he had left his home in the San Francisco neighborhood for the Pão de Mel bakery on Amazonas street, at the corner of Enoch Vieira de Almeida. There he would buy the morning papers and have breakfast. He sued to chat with the bakery’s owner, Antônio Perciliano da Silva, and then carry on to the Rádio Capital FM radio station six blocks away. In the afternoon, he would host the 40-minute program "Boca do Povo" (Voice of the People) at the local affiliate of the Record television network.

Escaramuça and Perciliano had known each other for nearly three years, having got together through a common interest, politics. That day, the talk show host was late for the program scheduled to begin at 6:30 a.m. That is why on arriving at the bakery he left the engine of his automobile, a Ford Landau, running, grabbed the newspapers, gulped down his breakfast and went on his way. Unlike what had always happened, when the baker would accompany him to the door, this time he went out on his own towards his car parked outside.

At that moment, it is believed someone called to him. Turning around, he was hit by the first shot in the armpit. the assailant drew close and fired six more times from a 12 caliber revolver. Almost at the same time, a person at the street corner fired twice from a 765 pistol. One of the shots hit a tire on the Ford Landau. The second struck a magazine that was posted up inside the bakery. According to police, the assailants fled in a white four-door Corsa automobile with no license tag.

The people who were on the scene at the time of the crime said they could see nothing. When they heard the shots, they dived for cover. One of the witnesses, located by the IAPA, refused to talk, because, he said, if he did so they would slit his throat and that of the reporter. Another witness said, "I want them to forget me. When the tragedy occurred, I got scared and ran. Who would hang around there?"

Located by the IAPA, the doorman of a building across the street from the bakery who was on duty that October 29 said there were a lot of cars parked on the street at that time of the morning, but he did not notice anything unusual. On hearing the shots, he hid behind a showcase in the building lobby and only peeped out after the firing stopped and no one was around any more. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was retired from his job there.

Since 1994, Escaramuça went around armed because of death threats he had received. But at the time he was killed his 38 caliber revolver was in his car, on the floor near the driver’s seat. Also in the car were his cellular telephone, 50-real bills and his newly-purchased newspapers. The key was in the ignition.

Loved and hated in the city, Escaramuça’s programs were based on allegations of wrongdoing by officials or persons who committed crimes or otherwise engaged in unlawful activities. He also reported on colorful happenings, gave aid to the needy and ran job ads. the broadcasts reached virtually every city in the state. The television program aired locally and in the suburbs. That is why it is not strange that so many mourners attended Escaramuça’s funeral. His family says that more than 5,000 people from all over turned out.

After his death, one of his sons, Marcos Antônio Lopes de Faria, who worked as a reporter on his father’s radio show, received a telephoned threat. A person called from a public phone box at a local clinic to Marcos’ cellular phone, saying he had murdered Escaramuça and he (the son) would be next. The caller was never identified. Following Escaramuça’s death, Marcos took over hosting his show for a while. He currently works at FM Cidade radio station as a reporter and runs a market research and telemarketing firm. The director of Rádio Capital FM, Luiz Lands Reynoso de Faria, refused to talk to the IAPA about Escaramuça. "I am still traumatized," he said.

Escaramuça’s widow, Edeltraud Bretz de Faria, 52, avoided talking to her husband about the threats he had received. "I didn’t even like to listen to his show," she says. She believed her husband risked too much with his commentaries. He would shrug that off, saying, "The one who threatens doesn’t do anything."

Nearly four months before he was killed, Escaramuça had a bodyguard posted at the door of the radio station while he was on air. The aim was to prevent anyone entering the studio while he broadcast. Edeltraud recalls that once someone called her husband during the show threatening to bomb Escaramuça’s house. He did not think twice about it – he gave his address and challenged anyone out there to carry out the threat. That day, two motorcycles circled around the house. Escaramuça pulled out his revolver, turned the lights out and hid behind a tree. The motorcyclists, probably realizing they had been spotted, made off.

Edeltraud remembers two occasions on which she saw cars parked near her home on an apparent stakeout and a telephoned death threat to her husband. She said the call came from the husband of a former wife of Ecaramuça, with whom he had a son, Tiago. She said the boy’s parents did not like Escaramuça’s attempts to be near his son, despite their having officially recognized the paternity.

Friends of his relate that two days before his death Escaramuça was in a bar when a person came in and he asked to be moved as he did not want to shot in the back. Businesswoman Rosângela Barbosa Borges, with whom he was having an affair and who was in the bar at the time, said she never find out who the stranger was.

The inquiries go in different directions

The police investigation into the Escaramuça case was not restricted to identifying one sole suspect. The police had several hypotheses, but did not come to any conclusion.

One of those investigated was Francisco Augusto Tavela. In November 1997, Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, police chief Roberto Almeida Gil was engaged in breaking up a gang that transported stolen trucks to Bolivia and Paraguay. He suspected the trucks were exchanged for drugs. He had alleged involvement of police officers in the gang and several were arrested.

On November 5, as Gil was arriving home, three persons approached him. He was shot 10 times and injured, but managed to wound two of his three attackers. one was Tavela, who later died. The second, Paulo Rubens Reichel, fled and was found dead later that day in an abandoned car on highway BR 364, 10 miles outside Cuiabá city. "He was executed and police officers are suspected of having done it," Gil said. Found in the car was a page from the local Correio do Estado newspaper dated October 31, 1997, carrying a report on Escaramuça’s death.

Tavela would be recognized from a photo by employees at the Pão de Mel bakery as a customer that had been there 10 days before Escaramuça’s murder. Tavela’s death and that of his colleague eliminated any possibility of determining any participation by him and who was behind the murder. But Gil, since retired as police chief and now working at the Mato Grosso do Sul Transit Department, believes there might have been some relationship between the attack on himself and the one on Escaramuça, because both of them had alleged involvement of police officers in organized crime.

The inquiries also implicated four police officers jailed for extortion in Campo Grande in June 1998. The four were accused of taking part in the kidnapping of a Bolivian and his son "to pay off a debt." During the time he was being held by them, the Bolivian said he heard remarks that they had killed a talk show host outside a bakery. The head of the Homicide Division, Marco Túlio Sampaio Rosa, reported that the police officers’ weapons were examined and found to be the ones used to kill Escaramuça.

Escaramuça’s son Marcos is still receiving calls with information, suggestions or leads about his father’s murder. He follows up all of them, but with no success.

A climate of impunity makes the case hard to solve

Escaramuça’s death came within a context of violence and impunity in Mato Grosso do Sul. the state, located in the south of west-central region of Brazil, renowned for the lush landscape of the marshlands – the most extensive in the world and one of the main eco-systems of the planet, was created in 1979 when the former Mato Grosso state was divided into two – north and south. Many people emigrated there from Brazil’s south and southeast.

Campo Grande, the state capital, where Escaramuça lived, has a population of nearly 700,000 and in 1999 celebrated its 100th anniversary. Despite its appearance as a big, modern capital the impression that visitors have is that of a provincial town where everyone knows everyone else’s business.

The economy of Mato Grosso do Sul is based on farming and manufacturing, but its 375-mile-long dry and open border with Paraguay and Bolivia favors the spread of organized crime in the region and makes the state a corridor for drugs, stolen vehicles and arms. "It is a region where not only is there drug-trafficking but there are also mobile labs to refine cocaine," says Walter Maierovitch, who headed the National Anti-Drug Department and currently runs the Giovanni Falcone Brazilian Institute, which specializes in narcotics issues.

When Escaramuça died on October 1997 there was evidence of more than 100 armed crimes having been perpetrated in the state. This kind of crime became so common in Brazil that a Parliamentary Investigative Commission (CPI) was appointed in 1992 to look into contract killings, particularly in the west-central and northern regions of the country. The CPI functioned until 1994. In 2000 – two years after Escaramuça’s death – a new CPI, this time on drug trafficking, has taken up investigations into the links between hired gunmen and organized crime. Mato Grosso do Sul was the scene of the inquiries.

In a study of crimes committed by gunmen in Brazil, Professor Cesar Barreira in 1998 produced a profile of the deaths. Some characteristics coincide with the circumstances of Escaramuça’s murder. According to Barreira, in general after the crime there are attacks on the victim’s personal and financial life so as to hide the political motives for the murder. The gunmen demand financial recompense. It is common for an entire city to know who is behind the crime, but nothing can be proved against him. Generally, the hired killers get together in public plazas, bars or cafes to make contact or arrange deals.

In the cases cited by the professor, the contact (intermediary) is often a current or former police officer. It is known that the gunmen move about constantly, not staying in their hometowns, and remain anonymous. They commit successive crimes and their feats are well known.

The information gathered by the Center for the Defense of Citizens and Human Rights (CDDH), based in Campo Grande, and the Brazilian Lawyers Association (OAB) of Mato Grosso do Sul say that a common characteristic of summary executions and murders carried out by hitmen is that the victims are shot multiple times, mainly in the mouth, the neck and the back. In most cases the victim was arriving home or walking in the street.

Impunity is a long-time problem in the region. Between June 1995 and July 1997 (just three months before Escaramuça’s death in October that year), the CDDH recorded 231 cases of summary homicides and abductions on the Brazil-Paraguay border and in the Grande Dourados area of Mato Grosso do Sul (about 75 miles from the border). Among them were victims of mass killings and mutilation. The numbers only include surveys done after reports published in newspapers. the majority have not been solved by the police.

In just one week in 1994, 32 mutilated bodies were found near Campo Grande. In September 1995, journalist Gilberto Lima investigated murders on the border for the nationally-broadcast television program "SBT Repórter" and confirmed the participation of police officers in those crimes. He managed to tape statements by the then Military Police Colonel Adib Massad (now retired) of elite Border Operations Group (GOF) belonging to the Public Safety Department and set up to reinforce border control. In the recording, Massad referred to a "cleanup of bandits." He ended up being fired form his post, but he was elected as a city commissioner in Dourados, obtaining the most votes. After his report was published, Lima received death threats.

Created about 12 years ago, the GOF recently changed its name, becoming the Border Operations Department (DOF), with an increased role in combating cattle rustling. This agricultural element, very important in the region, raised suspicions that this group was some kind of death squad funded by ranchers. It is currently investigating alleged links between police in the DOF itself with a car theft ring in Campinas, São Paulo state, sending vehicles to Bolivia through Mato Grosso do Sul in exchange mainly for drugs and dollars.

It was in this context that Escaramuça did his talk shows. Jus before he died, he announced on the radio that he planned to disclose the names of hitmen in the Dourados region. His death had a great repercussion because he was renowned for his controversial stance. He denounced politicians and criminals, on both radio and television. But in a loud voice and at times hurling insults he railed against those accused of wrongdoing and mere suspects alike. The tenuous line between free speech and abuse, with unfounded accusations and pejorative remarks, is very common on radio and television programs in the interior of Brazil.

Although before his death he had exposed the activities of hitmen on the border, his shows also had a strong political bent. From 1988 to 1993 he was an elected city commissioner for the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB). One of the constant focuses of his attention was the speaker of the state Legislature, Londres Machado. Questioned by the IAPA, Machado responded through a representative of his office that he had nothing to say about Escaramuça.

The allegations and attacks hurled out in his radio show in some instances resulted in legal proceedings. One was brought by Military Police Colonel Paul Cezar Gomes Navega, currently adviser to the Department of the Environment. Members of Navega’s team when he headed the Forestry Police were criticized by Escaramuça. The colonel himself suffered a heart attack, allegedly brought on by Escaramuça’s remarks about his personal conduct.

Navega, 48, a 28-year veteran of the police force, told the IAPA that he was interrogated by police in connection with Escaramuça’s death. "The problem is that he sought to discredit the unit that I commanded," Navega said. "All the allegations he made I investigated and none was based on the truth. When he started to libel me personally, I filed a lawsuit. Many people would be suspects in his murder, because that gentleman would attack anyone, he sought to take any opportunity to sensationalize."

In the city, also well known were Escaramuça’s criticisms of Senator Juvêncio Cesar da Fonseca, mayor of Campo Grande in 1986-88 and 1993-96. "Escaramuça strongarmed politicians and businessmen," claimed Fonseca, currently vice-chairman of the Parliamentary Ethics and Decorum Council of the federal Senate. He said that this was one of the reasons his city administration in Campo Grande had been so criticized by the talk show host. He recalled that the two had entered political office at about the same time. And he denied that he or his wife had said they would like to see Escaramuça dead, as the latter had once claimed.

The extortion accusation was also made by a Campo Grande police chief. The family rejects the insinuations. "When he made an accusation, it was because he had proof and documents," said his son Alex. "He would not take any money to keep quiet." According to Alex, there were a lot of offers of this kind that he himself witnessed. "But if Escaramuça had an allegation in his hands, he would call the person concerned offering air space to defend himself," Alex said.

At the height of his broadcast career – at the time of his death his show had high audience ratings according to a survey by Rádio Capital FM – Escaramuça planned to run for the state House of Representatives in 1998. A friend of his, however, had advised him not to run. "He was earning more as a talk show host. If he had lived, he would be rich," the friend said.

It was Escaramuça himself who sold ads for his program’s sponsors. And he had many sponsors. That is why Marcos, his eldest son, is another one who rejects the accusations made about his father. "If my father had been an extortionist, we would be rich."

The police investigation is practically at a standstill

A Campo Grande district judge, who prefers to remain anonymous, looked into the police investigation in the Escaramuça case and was surprised to find a lack of details. "The investigation has turned up practically nothing, it is still in its initial stages," he observed. He is sure of only one thing – it was a contract killing, therefore carried out by a professional.

The investigation is continuing its course, assures Marco Túlio Sampaio Rosa, head of the Homicide Division. "There are several suspects, but we have not got to the mastermind," he said.

The first police chief assigned to investigate Escaramuça"s death was Paulo Magalhães Araújo, currently adviser to the board of governors of the Mato Grosso do Sul Prisons Department. For him, the case is not likely to be solved, because no one wants to talk about it – "unless one of the hitmen gets drunk and talks or something else happens." He added, "the number of sots was so big that people were more concerned about protecting themselves than seeing what was going on."

Because of its characteristics, the crime required at least three people, Magalhães remarked. He thinks the fact that the killers used imported bullets is not significant. "Everyone in the city has a caliber 12 weapon, it can be bought in any store, and in Mato Gross do Sul, due to its proximity to Paraguay, only imported ammunition is used," he said. According to Magalhães, when Escaramuça died many people in the city were already expecting such an outcome because of his "overbearing manner" in his shows. "Anyone could have killed him. He was a fat cat, a big guy, therefore easy to hit with a shot and everyone knew his routine," Magalhães declared. "We followed up every lead in the investigation."

State attorney Gerardo Eriberto de Morais, assigned to investigate allegations of police involvement in border crimes in Mato Grosso do Sul, remarked that the available resources are not always used in full. The lack of a well-executed on-the-spot investigation, for example, makes inquiries difficult and allows the guilty to continue to go free. "Police officers are not trained to secure the crime scene – sometimes a cigarette butt can lead us to the criminal," he said. Another factor hindering an investigation, he said, was the lack of eye-witnesses. "When people see that it is crime committed by a professional, they clam up because they know that if they talk, there will be reprisals."

Thanks to the representations of the Brazilian Lawyers Association (OAB) and the Marçal de Souza Center for the Defense of Citizens and Human Rights (CDDH), Mato Grosso do Sul in April 1999 got to have a witness protection program called Pró-Vita. But, like other such programs in Brazil, it is often lacks funding and the structure is not big enough to cope with the needs. "The witness protection service is an illusion," said Federal Judge Odilon de Oliveira, who took part in the Parliamentary Investigation Commission on drug-trafficking.

The impunity the region is also due to its proximity to the border, which enables criminals to flee to Paraguay and Bolivia, beyond the reach of the Brazilian police. Justice is rarely meted out to those behind the crimes because three or four people are usually involved – the mastermind himself, an intermediary and the hitmen.

For state attorney Adhemar Mombrum de Carvalho Neto, who took part in the investigations into Escaramuça’s death, this has been the most perfect crime committed for hitmen in his 12 years on the job, because they left no trail. The killer used a caliber 12 weapon and fired off six shots in just one second, which shows that it was a professional. While this was going on, another person was shooting at the bakery. "The shock was so great that the eye-witnesses ran for cover," he said.

Carvalho added that although a white Corsa car had been spotted at the scene, probably used by the killers, police had been unable to find it. One of the eye-witnesses was said to have seen a person in the car using a cellular phone following the murder. He said he had asked for a list of phone calls made at around that time, but this had led nowhere. "We tried to find possible enemies of Escaramuça – and he had a lot, it is known that he extorted people," Carvalho claimed.

He believes it is possible that the gunmen were not from Mato Grosso do Sul, because of the cost of the operation and the risk of being arrested. According to Carvalho, the cost of a contract killing increases in proportion to the repercussions of the case. "That was an expensive crime because the press became interested and there is greater repercussion," he said. "In addition, the rapid-fire shots indicate that the gunman knew what he was doing."

The obstacles to concluding the investigation are also linked to the lack of police and judiciary structure. In Camp Grande, Carvalho said, there are only four criminal investigators, one of whom is now retired, and the number of investigations is on the increase. Up to February 2000 the Homicide Division had just two detectives to investigate the toughest cases in a city of some 700,000 inhabitants. Today, there are seven investigators, but the overall structure, including detectives, amounts to no more than 25 people – a number still well blow what is needed.

"There is no policy to combat organized crime and hired criminals in Brazil," said Adenilso dos Santos Assunção, secretary general of the Center for the Defense of Citizens and Human Rights. "There needs to be a joint action by municipal, state and federal governments," he asserted.

|