August 5, 1977

Case: Rodolfo Fernández

|

Past Imperfect:

March 1, 2004

Jorge Elías

He was excited, as he had rarely been, apparently. Something, however, was going to cause him to become concerned, dissipating that initial reaction, that spontaneous enthusiasm, as he faced the challenge of moving from one side of the Atlantic to the other, going to the Argentine Embassy in Paris as a press officer. Marisa Presti, his wife, was hesitant. She knew it was a unique opportunity for her husband, Rodolfo Fernández Pondal, 29, a journalist with the Buenos Aires weekly Ultima Clave, and that with a daughter barely one year and eight months old it would mean jumping into a new life. But she was hesitant, fearful of the new and unknown.

The new and unknown were to end up setting a trap for them. “It was learned unofficially that late on the night before last journalist Rodolfo Fernández Pondal, belonging to the news department of the weekly Ultima Clave and a stringer for a number of publications abroad, was kidnapped,” the news report said. “According to sources, at 11:50 p.m. the day before yesterday Fernández Pondal was traveling in an Alfa Romeo automobile with the second secretary of the Swiss Embassy when on reaching Carlos Pellegrini Street on the block between Juncal and Arenales he noticed that they were being followed by a yellow Ford Taurus with two men in it.”

The story, published on Sunday, August 7, 1977 in the Buenos Aires newspaper La Nación, was short but accurate – everything in it was to coincide with later reports compiled by Fernández Pondal’s wife as she sought to find out the truth of what had happened, a truth that she could not accept for years – she needed proof more than anything else.

“The journalist got out of the car and walked to an apartment building where he repeatedly rang the doorbell,” the news report continued, “when he got no answer, he tried to go back to the car he was traveling in when the two men in the vehicle that had been following him brandished guns and forced him into the Ford Taurus, which then fled the scene. Later, the incident was reported to police at the 15th Precinct, where a case file was opened for unlawful privation of freedom with Judge Adolfo Lanús of Number 106 Division of the Dr. Carlos Garvarino court.”

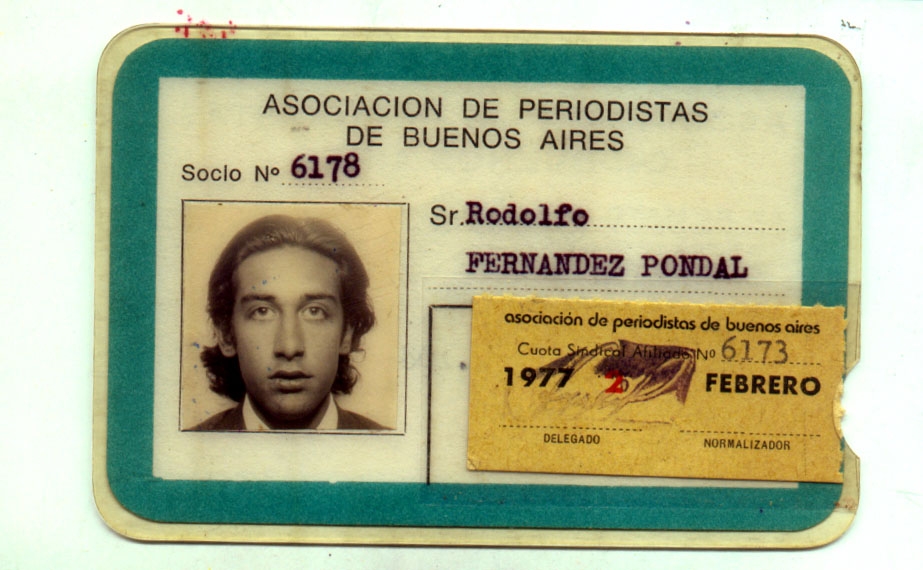

Rodoflo Jorge Fernández (his second last name, Pondal, was a pseudonym), identify card number 5,773,108, voter registration number 5,274,710, Journalists Association of Buenos Aires member number 6178, journalist registration number in process, pension fund carnet in process, had disappeared into that black hole of unsuccessful searches that was the methodology of terror applied by the Argentine military government since the coup d’etat of March 24, 1976 against all those presumed to be subversives or, in his case, dangerous.

He was the son of Rodolfo Luis Fernández and Hilda Beatriz Fernández. He was born on June 9, 1948, in the densely populated Buenos Aires neighborhood of Flores. An official of the Buenos Aires Civil Registry, on instructions from a federal judge, declared him presumed dead on January 5, 1982 – five years and five months after his abduction – and set the date of death at August 6, 1977, one day after his disappearance.

“Mr. Fernández Pondal is, according to the files at the Herald (which are not exhaustive), the tenth journalist to disappear since the coup,” said an August 24, 1977 editorial in the English-language newspaper The Buenos Aires Herald. “Only four of the 10 have appeared so far. One was found murdered. Four remain missing. For other professions – the hardships of lawyers come to mind – it could have been even worse. The fact is that a prominent journalist – no matter how shaken we might feel that anyone might kidnap someone of the integrity and honesty of Mr. Fernández Pondal – has been abducted. We must shed that extra skin that we have adopted to protect us from the suffering for the good of others. The government will take action only if the public reaction forces it to take steps to put an end to this gangsterism, which dates back to the apathy of the public and the official indifference in early 1970. The country will never recuperate if the lack of rule of law persists under the surface of life in Argentina, claiming numerous victims while we wash our hands of it.”

In the files of the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Conadep), set up in late 1983 by the democratically-elected government of Raúl Alfonsín with the aim of determining the whereabouts of those who one day did not return home, Fernández Pondal would be identified by the number 2620 among 84 cases of disappeared journalists (a figure later revised upward). “He was kidnapped on a public street in the capital (Buenos Aires),” later files indicated, “He was seen at the CCD (Clandestine Detention Center) of ESMA (Naval Technical Academy), with no indication as to the date.”

He had been seen alive, according to a listing made available in early 1984. There were said to have been three witnesses, according to an undated note from the Interior Ministry addressed to Federal Judge Miguel Guillermo Pons, in whose court the case was entered. They were Jaime Feliciano Dri (a former Montoneros leader and Peronist provincial congressman from Chaco province who fled to Paris on July 19, 1978 and who had been held in custody at the ESMA until Decmber 27, 1977 and at three clandestine centers in Rosario, Santa Fe province; Alberto Eduardo Girondo, also living in Paris after being detained at the ESMA, where he wrote political reports on the basis of books selected by the military), and an unidentified person.

At the Naval Academy officers’ casino on Libertador Avenue, Buenos Aires, near the River Plate soccer stadium, where the 1978 World Cup tournament was held, there operated Task Force 3.3.2, made up of members of the Naval Intelligence Service. It was on occasions turned over to the Army and Air Force. It had three floors. Detainees, who were tortured, were held in the basement and the attic.

Successive military leaders and those under their command have been brought to trial for those crimes, under terms of laws enacted during Alfonsín’s term of office. Among them were Navy Lieutenant Alfredo Astiz, who called himself Gustavo Niño as he pretended to be sad about the disappearance of a purported family member while infiltrating the rallies of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo (mothers whose children had disappeared and staged demonstrations in front of the presidential palace) in 1977, and his colleague Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, who had retired with the rank of captain, a.k.a. Miguel Angel Cavallo, Sérpico, Ricardo or Marcelo, implicated in the kidnap, torture and disappearance of 227 people, the torture of another 110 and the disappearance of 16 newly-born babies whose mothers had been abducted.

Cavallo was detained on August 24, 2000 in Cancún, Mexico, where he ran that country’s National Vehicle Registration agency (Renove). In proceedings initiated the following month by Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón in the Mexico Supreme Court seeking his extradition to Spain, Fernández Pondal’s name was on a list of more than 200 victims of the Argentine Naval Academy repression.

The list contained the names of people who were classified as Cases 1000. That means politicians, labor union officials, artists, journalists and church dignitaries regarded as dangerous but who were difficult to abduct because of their prominence,. Fernández Pondal was one of them, according to a March 22, 1984 report in the magazine La Semana. “He was one of the few Cases 1000 people to be taken out of the list for execution,” the report said. “A former employee of Radio Rivadavia radio station and joint editor of the confidential newsletter Clave Política (its correct name was actually Ultima Clave), Fernández Pondal was kidnapped by Captains (Jorge Enrique) Perren and (Alberto) González Menotti because ‘after flirting with Massera for a long time he wanted to go over to the side of Viola,’ according to the similar testimony of various survivors to the United Nations Human Rights Commission. After being held for several days in a la Capucha jail, Fernández Pondal was finally transferred.”

Transferred meant executed. “We do not know who made the decisions, we do not know whether El Tigre (Naval Captain Jorge Eduardo Acosta) one day got up and said, ‘Today I am going to make a transfer’ or if he chatted about it in the Libertad Building with (Emilio Eduardo) Massera (Army commander-in-chief, a member of the first military junta) and said, ‘Commander Cero, I have the floor full up, there are 40 of them, I am going to make a transfer.’ And he was the one who signed the paper,” said Miriam Lewin de García, a survivor of the ESMA. “We do not know whether we depended exclusively on their sympathy or antipathy, for us it was something completely hidden. There were people who had already ‘been put to work’ and then were killed. There were few of them, but they were there.”

From March 1976 to March 1977, Perren, a.k.a. Puma, Octavio, Morris or Inglés (Englishman), was chief of operations of the ESMA. He then was in Franxc, where he headed the Pilot Center of Paris, to which Fernández Pondal had been assigned – not to the embassy as his wife had at first presumed. The other person implicated, González Menotti, a.k.a. Luis or Gato (Cat), was an intelligence officer who conducted psychological operations from the Foreign Affairs Ministry.

Paris was having a party

In 1977, coinciding with the abduction of Fernández Pondal, the ESMA’s torture chambers carried the numbers 12, 13 and 14. “Transfers” meant death – on the day indicated, they would call people by their allotted number as picked out by a group of officers. They would take them out of their cells in the la Capucha cellblock (an L-shaped building) and to the basement by the “greens” (guards). They were given an injection of Pentotal (nicknamed Pentonaval, a play on words mentioning the Navy, by the captors) to make them drowsy. In that condition, they were taken to the military section of the Jorge Newbery airport in Buenos Aires and loaded onto airplanes, from which they were then thrown, still alive, into the River Plate or the ocean. Other methods of extermination were strangulation, application of electric shock, coup de grace for injured prisoners, lethal injection and the incineration of the bodies, known as roasting, as if it were some gastronomic feast.

On one occasion, Fernández Pondal’s late father, a retired army non-commissioned officer, was in a bar in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Constitución. He was on his own, drinking a cup of coffee. From a nearby table a man was bragging about the methods of repression. He was saying that some detainees were killed and at night were thrown from airplanes into the River Plate and into a lake in Mendoza province with stones tied to their bodies.

The father, Rodolfo Luis Fernández, out of his mind, stood up and brandishing a bottle, wanting to smash it on the man’s head, shouted that his son had been abducted and since then he had heard nothing from him. The man who had made the brutal comments about the exterminations was accompanied by another person that joined in the discussion, telling Mr. Fernández to watch what he was saying, because he was a member of the military.

At the ESMA, according to reports from survivors, there was a program under way to brainwash certain detainees in order to obtain their ideological support for the military dictatorship. They were subjected to servility, forced to carry out maintenance and electrical work, as well as falsification of documents, transcription of tape recordings, translations and writing essays on historic topics of special interest to the military authorities. There was another task linked to the leads concerning, or the causes of, the disappearance of Fernández Pondal – the handling and follow-up of news issued by the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) by teletype. That had been the job he was offered before these events occurred – to be part of the press office in the Argentine Embassy in Paris, to be part of the Pilot Center in Paris? The aim was “to have an influence in improving the image of the military authorities abroad with regard to the question of human rights in Argentina,” according to the indictment of Cavallo by Garzón – in military terms, “counteract the anti-Argentina propaganda,” something in line with the psychological war unleashed within Operation Condor, a multinational criminal activity in which the intelligence services of the Southern Cone countries participated.

Astiz intended to infiltrate groups of Argentine exiles in Paris and in Buenos Aires the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. The then Argentine ambassador to France, Tomás de Anchorena, had put to the military government “the need, precisely, to have a group of people who would manage the news well …. The idea was accepted but, in my view, it was distorted … instead of a professional team it became a team of people from the Navy …. They thought their obligation was more to their commander than to the head of mission …. My press secretary has clashes with these Navy officers who were heading the Pilot Center in Paris.”

The embassy press secretary was diplomat Elena Holmberg, a niece of former military President Alejandro Agustín Lanusse. It was her first overseas posting. She had to return to the Foreign Ministry because of the frequent clashes she had with Capt. Perren, who ran the Center for a while and who was named as one of those who carried out the abduction of Fernández Pondal. The Task Force 3.3.2 kidnapped her on December 20, 1978 in Buenos Aires and her decomposed body was found floating in the Luján River in Tigre, Buenos Aires province, on January 11, 1979.

An investigation into Holmberg’s murder carried out by her brothers led to a disturbing theory – that Massera feared she would reveal his membership of Masonic Lodge Propaganda Dos (P-2). This theory in turn led to a connection with the abductions of Fernández Pondal and the Argentine ambassador to Venezuela, Héctor Hidalgo Solá. Like her, both were aware that the chief of the Navy, nicknamed Almirante Cero (Admiral Zero) or El Negro (The Black Man), had received $1.4 million from the Montoneros to fund his political project, the Party for Social Democracy, creating a kind of truce in the campaign against the military government on the eve of the World Cup soccer championship, held in Argentina in 1978.

Lewin de García, a female journalist who was held at the ESMA from March 26, 1978 to January 10, 1979, having been abducted on May 17, 1977, learned of the existence of the Pilot Center in Paris. Another detainee, Mercedes Carazzo, had worked in France as the public relations chief for the Center, she testified on July 18, 1985 during the trial of the military junta leaders.

García also then learned of the disappearance of Hidalgo Solá from another kidnap victim, Lisandro Cubas. “It seems to me they did it to Hidalgo Solá,” she heard. There was a detainee with his charactersitics, but “we were not allowed access to him, he was kept completely apart from the rest of the detainees; when that person went to the bathroom, they kept us away from him.”

Fernández Pondal, like Holmberg and Hidalgo Solá, was close to Gen. Roberto Viola, successor of Jorge Rafael Videla as de facto president in 1981. Among Holmberg’s belongings was a photo of Massera with Mario Alberto Firmenich, the Montoneros chief, taken at the Inter-Continental Hotel in Paris during one of the clandestine trips that he was said to have made to France, Italy and Rumania, according to testimony by diplomats Gregorio Dupont (the brother of murdered publicist Marcelo Dupont) and Gustavo Urrutia. Also aware of this was a brother of hers, Enrique Holmberg, a retired Army lieutenant colonel.

At a meeting held at the home of María Cristina Guzmán (later congresswoman for the Jujuy Popular Movement and Argentine vice presidential candidate) was Viola. In April 1985, the then president of Aerolíneas Argentinas, Horacio Domingorena, disclosed during the military trial that he managed to ask him two questions: “If they were aware that the weapons that had been distributed among the paramilitary or parapolice groups could be turned against them in the future, and if they had in mind the abduction of Fernández Pondal. Viola replied to me that they were aware of that risk and in response to the second question he said that he had just spoken with Fernández Pondal’s wife and his disappearance could not be attributed to subversive groups, but rather that he had been abducted by other groups that had nothing to do with the guerrillas. Let’s hope, he told me, that one day it could be ascertained who had abducted him.”

What did Fernández Pondal know? Something, for sure. Something that not even his wife had been able to uncover in more than a quarter-century of doubts, of more doubts that certainties. Something that in subsequent chats with me over ashtrays that would fill with hazy images that culminated in loose ends, old contacts, absurd conjecture, amazing situations, humorless smiles, vague memories – a point of contention, a past imperfect in the face of the indifference of some of her husband’s colleagues, journalists like myself , capable of crossing the street from her so as not to be involved, not having to move a finger or take any action to help her, and help themselves, to shed light on the aberrant, implausible past, then the present.

It was so aberrant that, if it was up to her, she would only be prepared to give thanks for the efforts of the Herald’s editor, Robert Cox, a Briton. In December 1979, after sticking his nose into things so much, he had to leave the country with his family after receiving a death threat to one of his children in a letter signed by the Montoneros (he always suspected it was from the military regime). He had been held for 24 hours on April 22, 1977 for a breach of the security law. In 2001-02, as assistant editor of The Post and Courier in South Carolina, United States, he was president of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA).

“My husband dealt with a lot of information and had contacts with ambassadors and people from the Navy and Army, and Massera had even invited him to visit a submarine base,” Marisa Presti told me. “I never knew of any threats or anything like that. It was a matter of revenge, I believe. They had offered him a post at the embassy in Paris. And he was very happy about that. I had no great desire to go, but I had to accompany him. One night he told me he was not pleased with the idea any more and we were not going. I remember he had a stomach ache.”

They had been taking French lessons for a month. They were going with another journalist, Héctor Carricart, and his wife. That journalist, who wrote for a newspaper in Villaguay, Entre Ríos province, as far as she could learn, was said to have been the link between Fernández Pondal and ambassador De Anchorena, Marisa Presti said. A few months after the abduction he left for Switzerland, it would seem, and she never heard any more of him. But, she confessed to me, from the first moment she did not feel comfortable in his presence, something bothered her, she did not know what.

The key was in another phrase of Fernández Pondal that night when he decided not to go to Paris – “This is a second Graiver case.” That was the official motive that the military government used to shut down the newspaper La Opinión, run by Jacobo Timerman. Banker David Graiver, who died in August 1976 in a mysterious airplane accident near Acapulco, Mexico, came to own 45% of the stock of the company that published the paper, Olta S.A., and the Establecimientos Gráficos Gustavo S.A. printshop.

Inquiries by the military government concluded that he had funded the Montoneros from ransom obtained in the kidnapping of businessman Jorge Born in 1974, to the order of $60 million. Graiver’s bank in turn was collecting money for María Estela Martínez de Perón, known as Isabel or Isabelita.

La Opinón was a critic of the subversion. Graiver in 1971 had, simultaneously with the launch of the newspaper, been the mystery financier of a magazine that promoted armed struggle but at the same time he was traveling with the then president of Argentina, Lanusse. In his administration he held the post of Social Welfare Minister, to be replaced by José López Rega, mentor of the Argentine Antiterrorist Alliance (known as the Triple-A) in the government of Perón’s widow.

An unanswered prayer

Following the disappearance of Fernández Pondal, Cox was one of the few people to approach his wife. He took her to look at some documents at the Swedish embassy, they said he had been “transferred individually.” It was the death sentence, whch she deep down inside refused to accept.

Cox had a good relationship with the Swedish ambassador in Buenos Aires, Bertie Kollberg. “He and his wife did a lot to halt the ESMA’s torture and death machine,” he told me. “Clearly the Hagelin case was an early warning for them.” After seeing the documents, he gave Marisa Presti his impression: “I believe they have killed Rodolfo.” She did not agree with him, holding on to the hope of seeing him again and to live as before, or to live again.

The Hagelin case, however, had opened a door. It all began on January 26, 1977 around 5:00 p.m. with the detention of Norma Susana Burgos on the street, the work of an ESMA commando group that some hours later arrived with her at her home in El Palomar, Buenos Aires province. They searched the house and placed a guard of seven armed men on it. The guards were under the orders of Astiz. At 8:30 a.m. the next day Dagmar Ingrid Hagelin, a 17-year-old Swede, went to visit her friend Burgos. She was going to ask her if she wanted to go on vacation to the beach with her.

The guards thought that she was María Antonia Berger, a blue-eyed blonde like her, a Montoneros leader. They pointed their guns at her. She went inside, in panic, and then fled. Astiz, on the path outside the house, knelt down, pulled out his regulation pistol and fired just one shot. The bullet struck the girl in the back, leaving her injured. She was to be put in the trunk of a taxi belonging to a neighbor. The destination? ESMA.

Amb. Kollberg offered Hagelin diplomatic protection, he sent notes of protest and he met with members of the Argentine government. In early February 1977, the military junta (the triumvirate made up of Videla, Massera and Brigadier General Orlando Ramón Agosti) discussed the case in the Libertad Building, owned by the Navy. Ragmar, the girl’s father, had no hesitation in pointing to the person responsible – Massera. The one who had carried it out, by all accounts, had been Astiz.

In August 2003, with the Due Obedience and Final Point laws repealed and the cases of crimes committed at the ESMA and at the Army First Corps headquarters, interrupted in 1987 and now reopened, the Supreme Court decided to pursue the Hagelin case. It ordered the arrest of Astiz, who was sentenced in abstentia (he was in France) to life imprisonment for the murder of two French nuns, Alice Domon and Léonie Renée Douquet.

In the Herald, founded in 1876 by Scotsman William Cathcart, the editorials had to be published in both English and Spanish under terms of a law dating from the Juan Domingo Perón era. It was a whim of the general so he did not need to have recourse to a translator. A year after Fernández Pondal’s abduction a moving editorial was published, titled “In Homage.” It said, “Rodolfo Fernández Pondal was Argentina’s most highly regarded journalist. Foreign ambassadors invited him to lunch when they had to write a report on the Argentine political panorama. His contacts were at the highest level and he could pick up the telephone and call generals, admirals and brigadiers, who trusted and respected him…. Believing that Rodolfo would be saved by his high-level contacts, his friends and colleagues did not raise a loud alarm, the sole defense of the press, so vulnerable in a decade of terror …. Perhaps he was taken captive by the same people that abducted two other highly respected democrats who disappeared more a year ago, the then ambassador to Venezuela, Dr. Héctor Hidalgo Solá, and the former press secretary of the Presidency, Mr. Edgardo Sajón. Who knows? ….The only thing that is left for us to do is to pray …. Today we offer a prayer for Rodolfo Fernández Pondal and we also pay homage to all that he represented. If he is still alive, he will not have changed. His spirit is indomitable and he will win. We hope that this victory may signify his return safe and sound to his wife and little daughter. But if this is not to be, his victory will be in the final triumph of the principles for which he lived and for which so many men have given their lives.”

La Nación came out some days later in similar terms. “This case is definitively a testament of the high risk that working as a journalist has signified all these years,” the paper said in an editorial. “It is a case, among other, older ones and those of more recent times, on which no light has been shed. But for that very reason they underscore the degree of individual lack of safety that still exists in Argentina and of the relative vulnerability of the government to prevent there being groups prepared to share the use of force with it. What is serious about it is that they might well have shared it.”

Why did Cox, as few other people did, involve himself in the Fernández Pondal case. “I had two major reasons,” he told me. “I knew that it was possible to save a life by publishing a story about the person, especially in a case in which he was so obviously not a terrorist. The other reason was that the editorial policy of the Herald was to try to persuade the military government that its methods were unacceptable. James Neilson, an excellent writer, helped me with his conservative philosophy (liberal in the real meaning of the word) to make sermons directed at the conscience of the military and their civilian aides.”

In a meeting that he had in June 1979 with the Interior Minister, Gen. Albano Harguindeguy, following a press conference, Cox blurted out, ironically, “Look, the excesses are, for example, Fernández Pondal. Many journalists are excesses. Hidalgo Solá is an excess!” The minister, accompanied by the Deputy Interior Minister, Col. José Ruiz Palacios, replied, “Hidalgo Solá, yes. Fernández Pondal, I do not know how he died. Yes. I have no way of knowing if he is an excess or not.”

In vain Cox insisted, “But you have to do something for the people who are sincere, and there are many people who are. That is the big problem. As Mrs. Fernández Pondal told me, ‘What is the problem? My husband is a packet?’ She has found out absolutely nothing. They have not even called her from the Foreign Ministry telling her, ‘Well, madam, we have ….’ She does not know what to do.”

“I have not seen Hidalgo Solá’s sons for a long time now,” said the minister evasively. They have been in my office talking with me, chatting, several times after their father died and so on.”

“The investigation is all a joke,” said Cox.

“Zero. Joke, no. It got nowhere. Listen, Cox, listen….”

In a May 26, 1980 letter that Cox sent from Virginia to his friend Harry Ingham, a German-Argentine businessman living in Buenos Aires, he confessed, “I am particularly worried about the colleagues who have disappeared, and they will never silence me until those guilty of Fernández Pondal’s murder are brought to justice. Because one day they could choose to make other colleagues or friends disappear. I imagine that they would love to get rid of Manfred Schonfeld [a columnist for La Prensa] or Jim Neilson [editor of the Herald after Cox]. And as I feel so guilty for not having shouted louder when they took Rafael Perrota [editor of El Cronista Comercial] away and they asked his family for ransom, and many other innocent people, I am prepared to to whatever is necessary for them to know that I could (and without a doubt would) raise a storm of protest abroad if they start up their machinery of terror again. I realize what a devil’s accomplice I was and I must correct this now.”

In another letter, dated June 9, 1982, from Portland, Maine, he said, “I am fully convinced that the problem of the disappeareds needs an energetic battle to come up with solutions, that those responsible for the excesses must be punished and that the cases of innocent people – such as those of Hidalgo Solá, Perrota, Holmberg, Sajón, Pondal – must be examined.”

The enigma about Fernández Pondal has continued. Marisa Presti has not given up her attempt to find an answer. “Death needs a body,” she has written in a draft testimonial novel in which she sought to reflect the misery of being the wife of a man who disappeared during the military dictatorship, of being the widow of a shadow that for years, more than a quarter of a century, has been in every corner of her apartment in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Caballito, from which she did not dare to move, hoping, perhaps, that everything would get back to normal, that her husband, Rolo to his friends, would come back that night of August 5, 1977, the night on which he was seen for the last time.

“This was Rodolfo,” Marisa Presti – Sara, in her novel – says. “He was a very lively person, a journalist, like you, always running…. He loved what he did. He was capable of going a day without sleeping, sometimes having only coffee. He had a passion for getting the latest news before anyone else …. He was a young man with big, green eyes wide open yet fixed on nothing.”

The indifference of the world

That tragic Friday another life had begun for Marisa Presti (Alicia María Isabel Prestigiacomo, her real name), an advertising artist and university professor, and little María Paula, who was to become a journalism student when she grew up. That other life was marked more than anything by the lack of solidarity among friends and strangers faced with an insoluble dilemma – the disappearance of a loved one in a society that denied this could be true, a reality more tremendous and traumatic that death itself, perhaps, because of the lack of certainty of the whereabouts and at the same time a terrible feeling of suspicion for being family members of someone whose features have only amassed memories of an erratic course in which his wife, especially, received everything from promises from a military relative (“The packet is there,” “They moved the packet.”) to assurances from a clairvoyant – all unfounded.

The abduction coincided with threats against and persecution of other journalists, such as Edgardo Sajón, former press secretary of President Lanusse and news editor of La Opinión, and Enrique Jara, La Opinión managing editor, both of whom disappeared. The outcome was to be the newspaper being put into receivership on May 25, 1977, with a general as editor and Timerman leaving the country on a non-Argentine passport and a visa from Israel after being tortured at two clandestine detention centers.

Fernández Pondal, according to his wife, used to come home late. The day of his disappearance, dressed in jeans, a blue jacket (a gift from Massera when he visited the submarine base) and moccasins, he had left in mid-morning with a promise to come home early for dinner. “He asked me to wait for him, but at 10:00 p.m. he called me to apologize.” Around 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning she woke up alarmed. He had not arrived. “I worried a little,” she said. At 6:00 a.m. she called a retired general by the name of Pondar. Four and a half hours later she had the first indication – “He told me that they had seen him being taken in a yellow Ford Taurus.”

The description coincided with the story that was to appear the following day in La Nación. But it led nowhere. And Marisa Presti, married to Fernández Pondal on November 16, 1973 after being engaged for four years, felt torn apart, to the point that she threw the telephone to the floor and burst into tears. “I felt a tragedy inside of me,” she told me. In the next three years nothing was changed in her home. “Everything was there waiting for him,” she wrote. “His things, his clothes hanging in the closet, his breakfast cup, his towel. It seemed to me that at any moment the doorbell would ring and I was going to see him through the peephole on the door. I was convinced. But deep down my heart seemed to be sure of the opposite.” Simón, the family dog, no longer barked at the window as her husband played the horn of the Peugeot 104 that he drove. It was a sign to her, “an eternal sensation of the present suspended.”

The report of his disappearance was filed at the 15th Police Precinct, at 1156 Suipacha Street, Buenos Aires, near where he had last been seen. That is where the second secretary of the Swiss embassy, Luisa Caroni, said it happened. She was with him when the abduction took place, waiting for him in her car, a white Alfa Romeo, while he, aware that they were being followed, had decided to go to the home of a military officer that used to guard the door of the building where he lived.

That evening, it turned out, there was no one around. And then, getting no answer to the entrance buzzer, he went back towards the car where Luisa Caroni was. He had left there his clutch bag (commonly used in the 1970s and ’80s) – but he never got to the car.

A short time later, Marisa Pesti met with Luisa Caroni at a bar. And she found her husband’s black bag. In it, intact, were his identity card, diary, press card and his house keys, among other things. She then learned that that evening he had been at the Swiss diplomat’s home and that they had been talking about work – some Italian translations, apparently.

When they noticed that they were being followed (actually, he was being followed), they made a turn at the Obelisk and headed for the home of Col. Ricardo Flouret of the Army General Staff , a friend of Fernández Pondal’s. Caroni stayed in the car, at the wheel. “They don’t answer,” he said after the first attempt. When he tried again, he was surrounded by the two men who been traveling in the two-door Ford Taurus coupe. They stuck a gun in his back and his slim figure disappeared around a corner.

Caroni filed the police report the following day, first consulting with her ambassador and shortly afterwards she left for Switzerland.

“The diary was one of my solitary miseries,” Marisa Presti wrote. “Night after night I opened it and tried to translate every word, every punctuation mark, every line on the pages…. I studied the appointments he had prior to and after the drama, I stopped at every name of the people, I was trying to get conclusions. I had become a kind of useless Sherlock Holmes. Alone, sitting on the bed in our devastated bedroom, at times I stayed there until dawn coming and going through the pages of that famous diary.”

All the leads pointed to the ESMA. In 1988, President Carlos Menem announced its demolition. It could not happen – it was part of the national cultural heritage, according to a ruling by Federal Judge Ernesto Marinelli. Several years later, the Argentine president who failed to complete his term of office, Fernando de la Rúa, unwilling to restore to the city of Buenos Aires the land that it had given up in 1904, wanted to install an educational center there. But that could not be, either. Since February 9, 2004 the government of Néstor Kirchner, sensitive to the call to bring military officers involved in the repression to justice, has insisted on returning it to the city and converting it into a museum of remembrance.

Less than a month later, the Navy chief, Admiral Jorge Godoy, was the first to admit guilt for the atrocities committed during the Dirty War. “Just as the sun cannot be hidden behind a sieve,” he said, “you cannot make a valid argument to deny or excuse the commission of violent and tragic acts in that situation – facts that no one could justify, even in those very serious circumstances.”

This was on March 3, 2004, on the palm-fringed patio of the Libertad Building, before a Navy platoon in their white uniforms, on the occasion of the 147th anniversary of the death of Admiral Guillermo Brown – Navy Day. It was comparable only with the self-criticism of Gen. Martín Balza, the Army chief of staff, on April 25, 1995.

That day, from Bogotá, where a month earlier he had taken over as ambassador, Balza told me that only two lieutenant colonels, two colonels and one general knew the contents of the speech that he gave on Bernardo Neustadt’s television program “Tiempo Nuevo” (New Times). He said that the then Defense Minister, Oscar Camillón, had requested a copy and he promised to send it by fax. “Do you believe that it was sent?” he asked, smiling. “I talked on the telephone with the other chiefs of the general staff and, in a friendly way, I told them that I was going to give them a good answer. That’s all. I also spoke to my generals, but no political official knew what I was going to say.” In fact, he would not give the speech that day, but one month and four days later, on May 29 – Army Day.

Unlike him, Godoy had agreed with President Kirchner and Defense Minister José Pampuro on the terms of his reorganization of the force under his command, and curiously he failed at any time to mention the ESMA.

“I want ESMA,” he had told Kirchner and Pampuro months earlier. “Well, let’s see what I can do.” This must have been before March 24, the anniversary of the 1976 coup d’etat.

Open-faced

Fernández Pondal’s father at 1:00 p.m. on August 11, 1977 filed a writ of habeas corpus through lawyer Pablo González Bergez. He also requested information from “agencies of the Armed Forces and security forces.” It was all in vain.

Also in vain was his complaint to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS) in Washington, D.C. at the time of its mission to Argentina in September 1979 regarding allegations of numerous human rights violations. The case was logged as No. 5024. “The Commission has forwarded the relevant parts of your communication to the Argentine government, requesting that it provide the corresponding information,” the Commission’s executive secretary, Edmundo Vargas Carreño, said in a February 1, 1980 note to Rodolfo Luis Fernández. “Although dealing with the complaint may take some time, I would like to assure you that everything possible will be done to shed light on the incidents complained of and you will be informed of any development, decision or result in this regard.” He had less luck with another representation on May 23, 1980 to the director of the Office of International Law and Legal Affairs of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Karel Vasak.

Relatives of disappeared journalists, among them Fernández, asked the military junta for information about their whereabouts. They received no response. The list at that time, on November 18, 1980, totaled 72.

After trudging lengthily through the corridors of government, Fernández managed to have a meeting with Videla at 10:45 to 11:20 a.m. on April 26, 1979. He had requested it on March 1. At the meeting, according to a report that Fernández sent to the Armed Forces Supreme Command, after the normal greetings “the first statements of the president were: ‘We know that your son was an anti-terrorist, anti-subversive, anti-Communist, anti-Marxist, anti-Maoist and that he always acted open-facedly.’ I responded, ‘Mr. President, if you all know the way Fernández Pondal acted and thought, do you want me to believe you that you do not know what happened to him?’ He told me he really did not know.”

Videla admitted at that meeting that “excesses and abuses” had been committed. He was not talking to the father of a person that had disappeared but to a retired military officer. At one point in the conversation Fernández accused as being responsible for his son’s abduction Brigadier Generals Viola, Army Chief of Staff; Harguindeguy, Interior Minister; Guillermo Suárez Mason, Commander of the Army First Corps and chief of the Security Zone 1; Edmundo René Ojeda, the Federal Police chief; and Agosti, Air Force Commander in Chief; and Admiral Massera, Navy Commander in Chief, and Colonel Ramón Campos, Buenos Aires province chief of police. “Don’t talk like that about colleagues,” was the reply he got.

Fernández Pondal’s mother “had to undergo psychological treatment and I myself psychiatric treatment later, both under intensive care at the Central Military Hospital, otherwise my wife would have had to be sent to a mental institution,” Fernández had said in his request for a meeting with Videla.

In another paragraph, referring to his son’s Christian beliefs, he said, “His Excellency, Cardinal [Raúl Francisco] Primatesta [archbishop of Córdoba and special envoy of Pope John Paul II] was perfectly aware of my son’s thoughts and feelings, as he had a close friendship and communication with him through his role at Channel 10 TV in Córdoba and at Radio Universal there while he was their representative in Buenos Aires.”

In mid-1979 Videla described the Argentine press as “responsible and free, but more than anything responsible” during a press conference with Peruvian reporters that had accompanied the de facto president of their country, Gen. Francisco Morales Bermúdez, on a visit to Buenos Aires. He added, “That is our reality and there is not one, two or five that might be detained that deserve to be called journalists. That they ceased being journalists and became criminals. They made the choice and there they have the result of their choice.”

Was Fernández Pondal among them? His father wanted to know. The Interior Ministry’s director general of domestic security, retired colonel Vicente Manuel San Román, replied to him on October 15, “…I bring to your attention that, having gone through again the procedures with regard to the person in question, these have produced negative results to date.”

In a meeting with Massera he had the impression that things were being left to ride when Massera told him, “for me it’s a matter for the Army, without saying one way or the other.” The Army, in turn, told him that “it is a matter for Navy.”

In a “personal and confidential” letter to Videla dated December 9, 1980 Fernández, having exhausted all else, mentioned his granddaughter “so that tomorrow it does not cross her mind that her father might have been morally depraved and not an honorable man useful to society as in fact he was.”

Six days later Videla replied, also in writing, “…I would like to assure you of my concern at your serious problem and the anguish you are suffering at this time. I also want to let you know that the disappearance of your son, journalist Rodolfo Fernández Pondal, is still under investigation and therefore the case is not closed.”

Crossing in the air

Once democracy was restored, Ariel Lara, former cultural attaché at the Bolivian embassy in Buenos Aires, in August 1985 declared in the federal court presided over by Dr. Miguel Guillermo Pons concerning the disappearance of Fernández Pondal that he was “a professional who worked in a specialist news outlet, he was a brave and well-informed man whose articles, for those who know how to read between the lines, were truly important.” He had “excellent contacts,” he added, and what he wrote was “very accurate.”

Agreeing with this in an interview with me, Rubén Aramburu, a colleague of Fernández Pondal’s at Ultima Clave, said, “I never thought that the thing was going to go to such an extreme. Rolo had a very strong character. And he thought that with his experience at Radio Rivadavia (from which he had been fired) the magazine was going to become a springboard to the future.”

Ultima Clave was an eight-page, letter-size weekly magazine of political information sold by subscription. It looked like a newsletter. It had been launched on September 10, 1968. To make it lively, the subject headings were varied – What’s Happening, The Facts, The Situation, Events, The Climate, The Alternative or To Make a Comparison. The editor was Juan Martín Torres, with Fernández Pondal as managing editor – they had been friends since their teenage years.

“Rodolfo used to deal with the more civilized military officers, like Viola,” Aramburu told me. “We received no orders or money from the military. It was natural that he, being a journalist, would say what was going to be published. He thought he knew a lot about political analysis and he was very clever at digging out information, but he needed an editor.”

At the time he received the offer to go to Paris “the magazine seemed too small for him,” Aramburu said. “He wanted to get ahead. And if he could not do so one way, he would do it another way.”

Two months after the abduction Aramburu and Torres were arrested and held for 48 hours for no apparent reason. Torres made Identikits of two individuals (one 40 years old, the other 23 or 24, according to Fernández Pondal’s father). They had gone to the newsroom at Ultima Clave, at 717 Rivadavia Avenue, suite 404, Buenos Aires, for no evident purpose, some hours before the abduction. It was 9:30 p.m. They had asked him to publish a certain news item and said they would come back the next day.

“They were [intelligence agents],” Fernández Pondal concluded after closing the door behind them.

One of the Identikits, according to his father, bore the likeness of Navy Lieutenant Antonio Pernía, a.k.a. Martín, Trueno (Thunder) or Rata (Rat), who until 1978 was in charge of those who had been abducted and were “in the process of rehabilitation” at the ESMA. The father knew this from a photo of him published on page one of La Nación on February 27, 1987 taken as a number of Navy officers were testifying before the Federal Congress.

Three years after the abduction, Ultima Clave published a commemorative piece on its front page. It was almost an acknowledgement of impotence. “We can only say, after these three tough years, that we do not forget his warm friendship, that we miss his exceptional journalistic qualities, his sensitivity as a human being. And that we continue to fail to understand the absurd, psychopathic, bestial motivation of his aggressors, their lack of conscience,” the article said.

In 1977, shortly before his abduction, Fernández Pondal spent more time in Venezuela than expected. Marisa Presti did not want him to travel. In a photo he appeared with another man, unknown to her, on Margarita Island. Had he talked with Ambassador Hidalgo Solá? “We crossed in the air,” he told his wife. She did not know whether they had in fact crossed, one going and the other coming, on different flights or in the same aircraft.

They had crossed at Buenos Aires’ Ezeiza International Airport, according to one version, and there Fernández Pondal “had received information about an Argentine commando group in Venezuela communicated confidentially to then Ambassador Hidalgo Solá” by the Venezuelan president, Carlos Andrés Pérez , according to an investigation carried out by Rogelio García Lupo, Buenos Aires correspondent of the Caracas daily El Nacional.

Two members of that group, recognized by Venezuelan diplomats, were carrying false passports. They were Perren and Pernía, from the ESMA. They were going to kidnap Julio Broner, the leader of the General Economic Confederation (CGE) during the administration of Peron’s widow who was living in exile in Caracas since the 1976 coup. The plan, in which Navy Lieutenant Juan Carlos Rolón also participated, was to fire drug-loaded darts at him to paralyze him. But it failed.

Venezuelan intelligence, ruled by a democratic government, did not go along with the Operation Cóndor that the military dictatorships of Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador had put into effect jointly to deal with the so-called psychological warfare being waged from Communist nerve centers, for which reason, in principle, Perren, Pernía and Rolón could not count in Caracas on the usual facilities provided in other capitals for kidnapping and in some cases repatriation of those regarded as subversives or dangerous, such as Broner.

At the time when Massera refused to testify before Federal Judge Claudio Bonadío concerning alleged unlawful seizure of assets, Perren turned himself in, identifying himself as the chief of operations of “anti-terrorism” Task Force 3.3.2, because Rolón, his subordinate, had already been arrested. They both admitted in September 2001 that they had abducted journalist Juan Gasparini while he was a Montoneros leader, one of the ESMA survivors.

“When Hidalgo Solá traveled to Buenos Aires to report the matter to Gen. Videla, who apparently was unaware of the facts, he was kidnapped, just like journalist Fernández Pondal was 18 days later,” an article published in El Nacional on December 12, 1983 said.

Judge José Nicasio Dibur wanted to know the identity of the informers, but García Lupo refused to reveal it. To get the information he went the following day to Caracas, where, according to ANSA news agency, he came up with “a valuable witness who was said to have seen Hidalgo Solá and Fernández Pondal at Ezeiza Airport on the day that one was flying to the Venezuelan capital and the other was returning.”

A journalist quoted but not identified by the Argentine news agency Diarios y Noticias (DyN), close to Fernández Pondal and Hidalgo Solá had given a different version in 1982. “The diplomat in the days prior to his disappearance was seriously concerned at news items referring to himself that he regarded as distorted,” the report said. “The journalist recalls that on Monday, July 11, 1977 Fernández Pondal, who was then running the weekly Ultima Clave, asked him to drive him to the airport, from where he had to fly to Caracas on an apparently hastily-arranged trip. During the drive, Fernández Pondal revealed to his colleague that Hidalgo Solá would arrive back from Venezuela that same afternoon, so they would practically cross in the air, which meant they would not meet in Buenos Aires or Caracas as planned. Pondal asked his colleague to let Hidalgo Solá know he had left. The imminent arrival of the diplomat immediately aroused the interest of the press at the airport. Two days before, an Agence France-Presse report had attributed to him a demand for a rapid democratization of the country through the establishment of a civilian-military coalition government and it characterized the diplomat, a Radical Party militant, as the possible next president of Argentina. When Hidalgo Solá arrived at Ezeiza Airport at 7:00 p.m., two reporters were there waiting for him – the one whom Fernández Pondal has asked to give him his message and a representative of a Buenos Aires weekly newspaper. Before giving an interview, Hidalgo Solá was informed of Fernández Pondal’s departure for Caracas that morning. It was clear that this news upset him a great deal.”

Fernández Pondal, according to the writ of habeas corpus filed by his father six days after his abduction, “had been granted an interview with President Carlos Andrés Pérez.” From Caracas, on a previous visit, Marisa Presti had received a postcard from him, it was dated May 12, 1977, less than three months before he was abducted. He said in the postcard that he was missing her and meanwhile was drinking French Champagne.

Towards the end of that year, Marisa Presti received another kind of correspondence, a formal letter dated December 22. It said, “In the spirit of Christmas, a time for prayer and meditation, I wish to send you and your children an expression of my deep personal solidarity. I also fervently wish that the Lord our God may give you the necessary spiritual strength to face this time of anxiety for your household. I greet you with my most distinguished consideration.” The letter was stamped December 26, the day after Christmas Day . It bore the letterhead of the President of the Argentine Republic over the official coat of arms and it was signed by Videla – who was ignorant of the fact, among other things, that she did not have children but just one daughter.

She had had three meetings with him, all in vain. As in vain had been all the attempts to identify the whereabouts of Rodolfo Fernández Pondal – Rolo, as his friends called him – her husband, as she confronted a painful and discomfiting reality. For years she had had to even lie about her marital status to hide the fact that she was the wife of a missing person while she went on her voyage of misery with all its twists and turns in search of the elusive truth, just as a door had opened to her all that time ago and far away in Paris.

|