November 15, 2000

Case: Gustavo Ruiz Cantillo

|

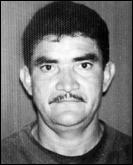

Gustavo Ruiz Cantillo, the son of Pivijay:

October 1, 2006

Diana Calderón Fernández

There are few places in Colombia where each and every peculiarity of a country come together as in the province of Magdalena, located on the North Coast. Not only because the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range rises up in the midst of a blue sea and a large percentage of the diversity has its own name – Taganga, Tairona Park and Santa Marta Big Swamp. But principally because Magdalena holds in its memory an integral part of Colombia’s history – the outbreaks of violence that it has suffered.

It is the area where the 1928 banana war broke out, where the bloodiest conflicts over the marijuana boom in the 1970s occurred and where the guerrillas and paramilitaries since the ’80s have been waging a bloody war for control of the territory and local political office.

According to a recent report in the El Tiempo newspaper the paramilitaries are said to have been responsible for some of the 2,000 murders committed in that province between January 2001 and September 2002. There have been seven journalists murdered in Magdalena province in the last 12 years.

Until just a few months ago, when demobilization of the paramilitaries was under way in Colombia, Magdalena province was for all intents and purposes under the control of the paramilitary bosses going by the aliases of Jorge Cuarenta, Hernán Giraldo and Chepe Barrera. In each township in the province there was a “big boss.” That is the case in the town of Pivijay, dominated by a group of several families headed by Saúl Alfonso Severino and Danilo Caballero.

Journalist Gustavo Ruiz Cantillo was a son of these lands. He was slain in the town’s market square at 5:40 in the afternoon of November 15, 2000. Two men trailed him closely and one shot him in the head from behind.

A month earlier he had been threatened by three unidentified persons who intercepted him at midday on a Pivijay street and without beating about the bush told him, “Don’t be such a bigmouth, because things can go badly for you.” Ruiz recounted the incident to a brother-in-law, who asked him to keep it quiet so as not to alarm the family.

According to the brother-in-law Ruiz had no hesitation in attributing the threat to his news reports, especially those concerning the increase in deaths and assaults in the rural area of Pivijay, which he blamed on “armed groups operating outside the law.”

José Ponce, news director at Radio Galeón radio station, said that the last report on violence that Ruiz did had done was eight days before his murder, and in that report he mentioned an assault on a motorcyclist on the Fundación to Pivijay road. “I remember that he ended the report saying that the authorities blamed the incident on the armed groups that had been creating a climate of apprehension in Pivijay and surrounding areas. He also said the same thing when someone was killed, but he always quoted the police as his source,” Ponce said.

But his last radio news item was not about crime. It was about complaints by power company customers in Pivijay of poor service and high costs. He also reported on a protest by teachers over delays in payment of their salaries, Ponce recalled.

The IAPA Rapid Response Unit was able to establish that Ruiz was investigating and exposing how paramilitaries were controlling everything in the province, including award of contracts by the local administration. He was also very concerned at the violence being unleashed by the paramilitaries – members of the self-styled Self-Defense Units.

The acts of violence at the time of Ruiz’s murder were increasingly frequent and bloody. Eight days after his death, on November 23, 2000, 60 men arrived at the village of Sitio Nuevo in the Magdalena Big Swamp, killed 45 people and were responsible for the disappearance of another 25. The then ombudsman, Eduardo Cifuentes, called on the military and political authorities to guarantee the safety of the local residents and said he had confirmed the existence of a paramilitary base in the Pivijay area, close to where the massacre had occurred.

Around the time of Ruiz’s murder also slain were brothers Manuel and Octavio Alvarez Caballero, the mayor of Cerro de San Antonio and former governor of Magdalena province, respectively.

Ruiz had worked for Radio Galeón in Santa Marta for more than 10 years, but it was only in the last three years that he had begun investigating armed groups. He started his investigations after confirming the direct involvement of paramilitaries in local politics in 1997 following the murder of physician Nicolás María Polo Pertuz, a Pivijay mayoral candidate for a local civic movement.

Ruiz studied at the National High School in Pivijay and in the late 1980s got into the radio business, working as a correspondent of the “Diario Hablado” news program broadcast by Radio Libertad in Barranquilla.

Julio Bolaño Lozano, president of the Magdalena Journalists Association, told the IAPA that with the murder of Ruiz a voice that always sought to tell the truth had been silenced.

Col. Hernán Bonilla Alvarez, who at the time was the Magdalena police chief, said that according to the result of preliminary inquiries Ruiz’s murder was connected to his work as a journalist.

“Hey, guy, about the murder of this man, everyone knows the paras did it,” a colleague told José Navias, an El Tiempo reporter, a few days after the murder. “The man was determined to complain about the lack of safety on the road from Pivijay to Fundación and they ordered him to shut up, as he was exposing the presence of armed men, patrols and kidnappings and nothing was being done about it. They tell me that even his family quit Pivijay.”

No one is pursuing the investigation. In May 2005 the IAPA Rapid Response Unit went to the area and the only thing to be found was a case file lying on the floor at the Santa Marta district Attorney’s Office. No one wanted to give any information about the case. The officials there preferred not to talk, out of fear of reprisals by the paramilitaries.

The investigation into Ruiz’s murder was initiated by the Santa Marta specialist Public Prosecutor’s Office under case number 20,227 a few days after the murder. On January 19, 2004, the Public Prosecutor’s Office classified the case as “subject to a restraining order on the grounds of expiration of the time limit established under the law, without it having been possible to identify the perpetrators or those who took part in the matter under investigation.” In this way the inquiries were suspended and the time to act was allowed to run out.

In August 2006, under pressure from the IAPA, the case was transferred to the Human Rights Unit in Bogotá and the investigation was reopened.

|