April 3, 2000

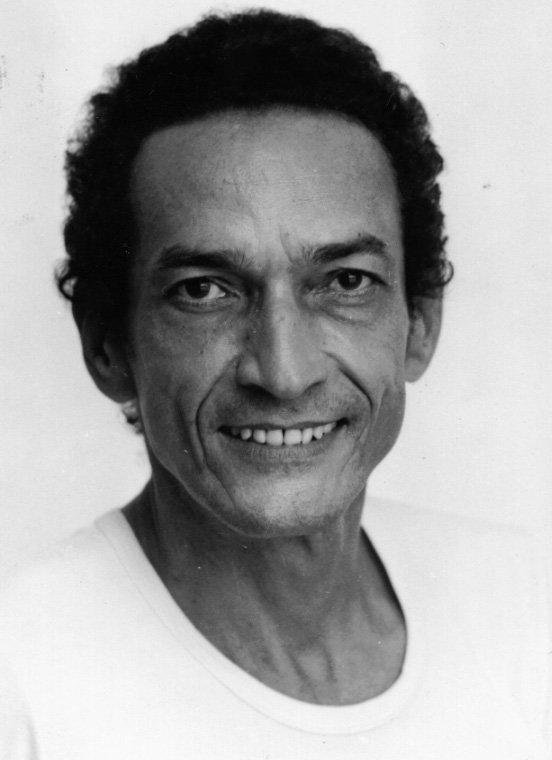

Case: Jean Leopold Dominique

|

Dominique was shot dead on April 3, 2000, as he arrived to work at his radio station.:

January 1, 2001

Ana Arana

Bodies have disappeared, suspects have died unexpectedly and the cast of characters who are said to have conspired to kill 69-year-old Jean Leopold Dominique, Haiti’s most prominent radio journalist, is a story more colorful than any a mystery writer could dream up. Dominique was shot dead on April 3, 2000, as he arrived to work at his radio station.

Bodies have disappeared, suspects have died unexpectedly and the cast of characters who are said to have conspired to kill 69-year-old Jean Leopold Dominique, Haiti’s most prominent radio journalist, is a story more colorful than any a mystery writer could dream up. Dominique was shot dead on April 3, 2000, as he arrived to work at his radio station. The first list of suspects was long--former supporters of the Duvalier dynasty as well as corrupt businessmen. But recently, the investigation indicates that Dominique, a key advisor to former President René Préval, and a friend of President Jean Bertrand Aristide, apparently was a victim of an internecine conflict among members of Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas political party.

An investigation by the Inter American Press Association (IAPA) has found that Dominique, a man who spent his life defending Haiti’s poor, combining journalism with leftist political activism, was killed in a political conspiracy apparently planned and conceived over several months by leading political figures tied to Aristide. Among those named in the official investigation as possible suspects are Sen. Dany Toussaint, a Machiavellian figure who commands a lot of power inside Lavalas, and several of his allies who serve in the Aristide government or are members of the Haitian Senate. These officials, the investigation indicates, viewed Dominique’s independence and honesty as a threat to their quest for power, and their involvement in corrupt businesses, according to sources close to the investigation. A number of sources provided valuable information to the IAPA on this investigation. But because the murder conspiracy involves powerful figures in Haiti, most sources agreed to talk only if they were not identified in the report. The threats against the judge, witnesses and investigators on this case are palpable. Already last January, a man who was allegedly passing on information on the crime was killed in broad daylight in Port-au-Prince.

Even Dominique’s widow, Michele Montas, who is legally able to learn details about the investigation, was reticent to share much of her knowledge. "I am part of the investigation so I have to be careful what I divulge publicly, " she said.

Dominique’s assassination shocked Haiti, because he was seen as an unconditional, if critical, Lavalas supporter. His death was a dire signal that the movement President Aristide built in the 1990s in opposition to the corrupt Duvalier dynasty has serious internal rifts. Before his death, Dominique harped that a patchwork of corrupt officials with links to criminal networks, including drug trafficking and car theft, had taken over the political party. He had named influential, corrupt Lavalas officials in his radio programs, in the hopes of promoting their dismissal from the party. "Dominique thought he had more political clout than he did," said a foreign observer.

Haiti today is more divided and impoverished than when President Aristide was returned to power by the U.S. Army in Oct. 1994, following a military coup that ousted him from office for three years, after winning the 1990 presidential elections. Several political murders have shocked Haiti in the last few years, but none of the victims was a loyal, long-term Lavalas member like Dominique. During the first ten months after the murder, the government lost precious time following false leads, and the investigation was seriously stalled.

Not until October 2000 did the case advance significantly. The reason apparently was outgoing President Préval’s willingness to use his last remaining months in office trying to solve the murder. The Préval administration allocated more money for witness protection, for bodyguards for Dominique’s widow, and for security for the investigating judge, a man who has received serious death threats. Préval’s decision came despite internal suspicions among Lavalas party officials that the case could have a negative impact on President Aristide’s second term in office. As an example of this paranoia, party officials have directly told Dominique’s widow, Michele Montas, that the case is dangerous for Aristide.

The IAPA believes a quick resolution of the Dominique case should be held as a litmus test of the Aristide Administration’s decision to respect press freedom in Haiti. Already Dominique’s murder has had an indelible impact on how journalists do their work. Several threats against the press have prompted international response, but the use of vigilante mobs to pressure the news media against critical reporting apparently continues to be promoted by top Lavalas officials.

Dominique had a violent end in a country where political allies quickly become enemies. "What people don’t understand is that these officials who are in power today are determined to stay there and won’t do anything they fear is going to affect their power base. Dominique was so close to power he underestimated the danger," said Marvel Dandin, of Radio Kiskeya, an independent radio station also under attack by Lavalas supporters.

Aristide was elected president last November after contested legislative and presidential elections. Most of the opposition refused to participate in the presidential elections. Today that opposition, united under a group called the Democratic Convergence, which includes most political parties, in addition to former Lavalas people, refuses to compromise and has elected a symbolic parallel government in clear defiance of Aristide.

Aristide’s second term as president begins as the country faces its worst political, economic and public safety crisis. Unless he comes to an agreement with the opposition, the country won’t receive $500 million in international aid. International aid is necessary. Haiti is the poorest country in Latin America according to the United Nations—with 80 percent unemployment, a 15 percent inflation and a population growth of 2.1 percent. The next few years will be difficult for Haiti.

Most intellectual and political sectors in Haiti say Lavalas has contributed to the crisis by its incapacity to tolerate dissent, and its willingness to look away in the face of corruption among its members. Lavalas remains a powerful political force because of Aristide’s cult popularity among the Haitian poor.

Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas party has become a haven for vigilante groups, known as Chimères. These vigilante mobs are allegedly hired to frighten the opposition. During Dominique’s funeral, these protesters burned the political party headquarters of opposition leader Evans Paul, a former Aristide ally.

Most sources with knowledge about the Dominique investigation said they believe President Aristide was not interested in getting rid of Dominique, the most prominent Fanmi Lavalas leader killed to date. But foreign and Haitian sources believe sectors within Lavalas are completely independent of Aristide. They point out that Aristide’s failure to publicly denounce the Dominique murder, other political assassinations, and attacks against the opposition and the press, have only encouraged more abuses.

Others are even more openly critical of Aristide and cast more doubts on the role he plays in Haiti’s political circles. "He continues to be an important figure in Haiti and in Lavalas," said one source. "In these matters you don’t have to say a word. A nod, or a gesture, can been interpreted as tacit approval," said one Haiti expert.

Michele Montas, Dominique’s widow agreed. "I don’t think Aristide had anything to do with anything related to Jean’s death. But he doesn’t control everyone in his party," she said adamantly when asked about the possibility. Montas remains shaken up by the decision to murder her husband who remained a loyal party member until his death. "It’s ironic," she said. "We never dreamed this was a possibility."

Close Aristide associates said Dominique was hated by many people because of his acid editorials in a country where people are more muted in their criticism of others. Brian Concannon, an American lawyer who works with a legal aid group formerly called Lawyers for Aristide, said many people wanted to get rid of Dominique. He also argued that Western journalists were too willing to point the finger to people close to Aristide just to hurt the newly elected president.

US policy

Six years after Operation Uphold Democracy, which brought Aristide back to Haiti in an ambitious military display, and approximately $3 billion in international assistance, the Clinton Administration’s Haiti policy is being declared responsible for the current debacle in Haiti. "What happened with the Clinton Administration is that they wanted a success so badly they never questioned problems as they surfaced, and as a result the situation just got messier," said one congressional source.

US Haiti policy has been marred by the fact it became so divisive in Washington during the Clinton Administration, pitting Democrats against Republicans in a manner not seen since the Nicaragua Contra War. Complicating the issue was the fact that key policy makers became too involved in Haitian politics. Several members of the Congressional Black Caucus, for instance, serve in Aristide’s Foundation, sending mixed signals to Haitian officials. Similarly, such organizations as the International Republican Institute (IRI) had as its in-country director a Haitian-American whose family had been pro-Duvalier. IRI was forced to close its office after several attacks against its representatives and headquarters.

Aristide supporters are highly suspicious of anything American, but they still want the aid, which is partially American and European. IRI’s involvement in helping organize the Democratic Convergence, the loose anti-Aristide opposition umbrella group, has been another pebble in the shoe, in this highly paranoid country. So willing are people to believe in American malfeasance that a rumor that Dominique was killed by the Americans was credible in the first months after the murder. Aiding that rumor was an unfortunate incident where a key informant and possible hit man in the case turned out to be a Haitian man who had an independent relationship with the Public Affairs office at the US Embassy.

Until his death Dominique was intensely critical of U.S. policy. He thought conservative sectors in the United States wanted to finish Lavalas and posed a danger to Aristide’s hopes to win a second run for the presidency. Thus months before his murder he criticized the role of US organizations such as the IRI, IFES and USAID, which were directly involved in the initial preparation of May’s legislative elections. In his typewriter, he left an unfinished editorial on the role the United States had played in Haiti since 1917.

Ironically, as with anything in Haiti, it is the country’s nemesis, the United States, that gets the ball rolling. In the Dominique case, it might well be US attention that may convince Aristide to take the case to court, despite serious opposition within his party. The US is interested in the case because it is a good vehicle to tackle powerful Haitian government officials involved in drug trafficking.

But Joanne Mariner, Deputy Director for the Americas at Human Rights Watch, said it was important for the Bush administration to move forward beyond drugs, and look at the Dominique murder and other political assassinations, as a way of helping Haiti improve its judicial system and end impunity.

"Human Rights Watch will be closely following the progress of the investigation into Dominique’s killing, and, in our view, so should the Administration. The outcome of this case will be an important indicator of the strength and reliability of the Haitian justice system," she said.

The journalist

An irascible and critical reporter, Dominique made many enemies because of the caustic editorials he delivered on his morning and afternoon radio shows. His enemies at the time of his death ranged from far right Duvalier supporters to far left Lavalas populist supporters.

The son of a mulatto, upper-class family in caste-ridden Haiti, Dominique was considered an enemy of his class because of a lifelong support for the poor in Haiti. A trained agronomist, Dominique turned to radio journalism in the 1960s with a one-hour program he hosted on a time-leased slot on Radio Haiti. By 1971, he had purchased the station, and began a meteoric rise in the profession because of his bombastic style and willingness to challenge abuses of power.

A passionate speaker, with a colorful command of French and Creole, Dominique used the radio waves to oppose Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, his son "Baby Doc", and the military juntas that ruled Haiti until the early 1990s. He was exiled twice. In 1980, after his station was destroyed, he went to the United States with his wife Michele, and returned to Haiti only after a popular revolt overthrew Baby Doc Duvalier in February 1986. In 1991, when a military coup ousted President Aristide, he again went into exile in the U.S., only returning in 1994, when President Aristide was brought back by the U.S. military.

He became extremely popular throughout Haiti, especially among peasants in the countryside because his station often addressed issues of land ownership and agriculture. His station was the first to offer Creole-language radio programs, a decision later copied by others in a country where 90 percent of its citizens are illiterate and speak Creole, not French, the official language. "Dominique helped lay down the groundwork for an independent press in Haiti," wrote Jean Jean-Pierre, a journalist who lives in New York.

Dominique and his wife hosted Inter Actualites, Radio Haiti’s most popular morning show, which included news reports, commentary and editorials. Montas, a US-trained journalist, delivered the national news, while Dominique read international news, and wrote the station’s editorials and commentary, which were sizzling tirades against corrupt politicians and businessmen.

An early Aristide supporter, Dominique embraced his handpicked successor, President René Préval, who served from 1996 to February 2001. Also an agronomist, Préval and Dominique both believed in bringing change in Haiti through political access in the countryside. Together they founded Kozepep, a peasant organization that could congregate thousands of peasants for political meetings and began to run into problems with the Lavalas leadership, who saw it as competition. Several Kozepep members were attacked by Lavalas in Haiti’s interior. Although many serious problems affected the Préval government, including his decision to dissolve the Parliament, Dominique had hope with Préval.

"He was more of a politician than a journalist," said Max Chauvet, editor of Le Nouvelliste, the leading daily in Haiti.

A casual dresser in this tropical capital, where men wear coats and ties in 90-degree weather, Dominique preferred to work in shirtsleeves and shoes without socks. But he was an unbending moral conservative. He told his wife he would not permit Lavalas, which means cleansing flood in Creole, to become dominated by corrupt officials.

Dominique remained supportive of Aristide, according to Montas. Even at times when other prominent Lavalas members became part of the growing Aristide opposition, Dominique stayed with the party. In 1996, for example, when leaders of the Lavalas Political Organization (OPL), which supported Aristide’s first election in 1990, refused to endorse Aristide’s desire to lengthen his first presidential term, and broke off, Dominique stayed on. Dominique joined Aristide’s new Fanmi Lavalas, helping rescue the Lavalas’ popular name recognition away from the other party, which became known as OPL. Dominique told Aristide on several occasions he needed to clean up Lavalas of unsavory characters who were engaged in corruption and drug trafficking. In the end, Dominique seemed to have been failed by those he protected.

"Jean’s motto was transparency, truth and participation," said Montas, an elegant, soft-spoken 54-year-old woman who continues to run Radio Haiti, and is determined to keep her husband’s name in the news until the case is solved.

In May 2000, a month after Dominique’s murder, Lavalas won 72 of 82 Lower House seats and 18 of 19 Senate seats. They won another eight seats in the November elections. But the tabulating methods used to count votes in the May elections are hotly contested. Vote counting in nine areas was declared irregular by both the Haitian opposition and independent international organizations such as the Organization of American States (OAS) and the United Nations. "If Dominique were alive, he would not have allowed this to go unnoticed," said a political observer.

The Crime

The day he was killed, Dominique arrived at the radio station at his usual time—shortly after 6 a.m. to have a few minutes alone with his editorial. The news show started at 7 a.m.

The killers apparently watched the station for two weeks prior to the murder. During that time Michele Montas had been arriving at the station with Dominique because of a back problem. That was not their normal routine. They had different schedules and preferred to take different cars. As fate would have it on April 3, 2000, Montas was driving herself for the first time in days. "Apparently they had two shooters. I suppose one was for me," she explained in an interview in her second floor office at Radio Haiti Inter.

Dominique drove up to the station’s entrance on Delmas Road, a thoroughfare connecting the upscale neighborhood of Petionville and downtown Port-au-Prince. Jean-Claude Louissaint, the security guard, opened the blue metal gate. One man was loitering nearby, but Dominique did not pay attention. Two cars were parked in front of the station with other men inside.

Dominique parked and took a few steps towards the station’s door. The man loitering entered the gate on foot. Catching up to Dominique he pulled a gun and shot him seven times with deadly hollow-point bullets—in case he was wearing a bulletproof vest. One shot pierced his aorta. The gunman then shot and killed the security guard. "Jean would not have survived his wounds," said Michele Montas, who found the bodies when she arrived at the station a few minutes later.

The Investigation

Dominique’s death provoked demonstrations and massive displays of mourning. Eighteen thousand people attended his funeral and a ceremony at the soccer stadium. But ten months later, the culprits have not been brought to justice. Six men are in prison, accused of being either material killers or accessories to the crime. But the investigation inches slowly, hampered by the deteriorating political situation in the country and emboldened displays of bravura by people investigators said were involved in planning and carrying out the murder.

Bizarre incidents have complicated the murder investigation, putting in display Haiti’s penchant for drama and occultism. Last July, Jean Wilner Lalanne, a key suspect died after an orthopedist extracted bullets lodged in his buttocks, an injury he obtained as he attempted to escape when he was arrested. A member of a car theft ring, Lalanne was said to be the contact between both the material killers and the intellectual killers. He was believed to have provided the getaway cars. When police asked for Lalanne’s body for an autopsy, it had disappeared from the morgue. Hospital sources said it was probably buried in a common grave, where they dispose of unclaimed bodies. The hospital apparently buries bodies quickly since electricity is cut off for hours during the day because of energy shortages. The explanation is odd, since hospital staff knew Lalanne was an important suspect in the Dominique murder.

Another surprising development is that the orthopedist who operated on Lalanne was later charged with involuntary homicide by the investigating judge. The doctor was not in Haiti at the time the charge was laid.

Two influential lawyers, Jean Claude Nord and Gerard Georges, who are also suspects in the case because they threatened Dominique in a radio program a few weeks before the murder, represent Senator Dany Toussaint, a suspect in the case.

Then there are the "chimères," screaming Lavalas protesters who are brought out to challenge the opposition and are reportedly paid for their services. They have come to scream at the judge every time he hauls in suspects for questioning in his chambers.

Lavalas leaders claim chimères are out of control Lavalas fans. Haitian journalists say the chimères have leaders who command their screams. Such a leader was in the news in January. Paul Raymond, head of the Lavalas Little Church Community, which operates out the ruins of St. Jean Bosco, the old parish where Aristide began his career as a priest, sent shivers down the backs of 80 Haitians journalists, clerics and politicians when he warned chimères would kill them and turn their "blood to ink, their skin to parchment and their skulls to inkwells," if they continued with their opposition antics.

Haitians took the warnings to heart, and the government was forced to haul Raymond to court to explain the threats—his lawyer was the ubiquitous Jean Claude Nord who also represents Toussaint and is a suspect in the crime. During a quick visit to the church ruins in downtown Port-au-Prince, chimères were being put in trucks and Lavalas leaders were giving final orders to a group of cars taking protesters to a site.

Chimères can get out of hand. In the past mobs have engaged in "Pere Lebrun," which means you kill someone by placing a burning tire on the neck of the intended. They have burnt down opposition headquarters and staged disorder in front of newspapers and radio stations they see as their enemies.

A "petit" Judge

Judge Gassant is a small, thin man with a quick smile. A graduate of the National School of Magistrates in France, he is part of a new crop of judges in Haiti who take their job seriously. Asked why he took the Dominique case, he said he "could not refuse the offer because of his professional integrity." But people in Haiti like to say the judge is practically carrying a "coffin under his arm."

Between October and January, the judge worked freely if teetering with fear. The investigation is treacherous, and Gassant who makes arrests with a group of policemen who wear masks to avoid recognition, was not shy to express his terror. He never expected the pressure to be so relentless, but he is hanging on. He has opened a parallel investigation on the Lalanne murder to determine if there was gross negligence, or a direct attempt to silence a key witness.

Gassant is the third judge on the case. Two judges resigned following death threats. Gassant took on the case for the prestige and legal challenge and is hanging on by his fingernails. He broke down in tears one day, during a brief interview. He takes to heart the rules and regulations of the proceedings, which means journalists have no access to the investigation. It is part of the secrecy required under Haiti’s Napoleonic legal system.

The Dominique case documents are stashed in two big cardboard boxes which the judge keeps at an undisclosed location. His family has left Haiti, and he sleeps in a different house every night. He travels around town in a number of unmarked cars with bodyguards and swat team members. The killers loom in the darkness of Port-au-Prince, or hide among pedestrians crisscrossing in front of cars in Haiti’s notorious traffic jams. Dozens of political killings in the last five years have occurred on clogged city streets.

A few weeks ago, the judge thought he had a close encounter: his car was cut off by the car of Milien Rommage, a Lavalas deputy and former number two at the presidential palace’s security force. The unit has been cited by international observers as the place from where several political murders were planned. Recognizing the judge’s car, Rommage yelled that he could easily spray the car with gunfire. The remarks were supposed to be in jest, but the judge has received several death threats, and the encounter came as he battled the Lavalas-controlled Senate, which was threatening to investigate him because he was attempting to summon Dany Toussaint, who was elected Senator in the May 2000 elections.

Yvon Neptune, president of the Senate and a Toussaint supporter said the judge’s request to question Toussaint was unacceptable coming from a "petit" judge, which translates roughly as an insignificant judge.

The driving force behind the Dominique investigation is Michele Montas, a top journalist who never delved into Haiti’s underworld until her husband’s murder forced her to look at a Haiti she did not know. "Jean was murdered because he was going to stop a lot of people from making a lot money," she said. She uses the radio station and whatever few connections she has in the Aristide government to twist arms and move the case along.

Montas met Dominique when she came to work for Radio Haiti in the early 1970s. Fresh from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where she witnessed the 1969 anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, Dominique swept her off her feet with his passionate politics. Married for 25 years at the time of his death, Montas has suffered tremendously with the murder. She considered closing the station, but with the help of Dominique’s daughter Gigi, she resumed operations a month after his death. She also swore to solve her husband’s murder. It is a dangerous mission, to boot. But she is determined. "They killed me when they murdered my husband," she explained, in her soft French-accented English, her eyes welling up with tears.

The Préval government gave her four bodyguards who follow her everywhere. She still seems in shock over her ordeal. Images of her husband are everywhere at the radio station and in her home. At Radio Haiti, a life size portrait of a photogenic Dominique welcomes visitors. At home, his pipes and leather cap remain where he left them.

Montas remains under intense scrutiny by those who planned and executed her husband’s murder. She sometimes gets more bodyguards. "When the trail gets hot," she said with a nervous laugh. She has written her will but doesn’t believe the killers will come after her. Limited by the secrecy surrounding the investigation, she only writes stories on the case when she fears the investigation is being sidestepped. "They thought I was going to go away because I am a woman."

In February 2001, before the Aristide presidential inauguration, for example, Montas suspended all transmissions at Radio Haiti for three days. The action was to protest a motion to investigate Judge Gassant by the Lavalas-controlled senate after his third attempt to force Sen. Toussaint to testify. "They have to understand that there won’t be impunity in this case," she added, although she is aware she will need international support to get the case through Haiti’s labyrinth-like judicial system.

Who killed Dominique?

In plot-ridden Haiti, everybody points the finger at everyone for the Dominique murder. Threatened all his life, Dominique had no specific warnings on the days prior to his murder.

To begin the investigation, Montas gave the prosecution a list of potential enemies who could have had Dominique murdered. They included businessmen he had accused of alleged corruption in his daily editorials, politicians and former Duvalier supporters.

Initially, Lavalas strongly pushed forth the theory Dominique could have been killed by former Duvalier followers. One name that surfaced was that of Leopold Berlanger, an opposition figure and owner of Vision 2000, a radio station that has also been attacked by Lavalas. Last year, Berlanger was coordinator of the Council of National Observers, a body overseeing the May legislative elections. Dominique was openly critical of Berlanger in one of his last editorials, charging him with being part of a coalition "engaged in the destruction of Lavalas." Berlanger has cooperated with the investigation and is no longer a top suspect, according to sources with knowledge about the investigation.

Berlanger sent a letter to this office on March 16, 2001, to make some clarifications which are included at the end of this article.

Instead, Haitian and foreign observers and investigators in the case have looked for clues in a radio editorial Dominique delivered on Oct. 19, 1999, six months before his death. The editorial was a direct attack against Dany Toussaint, who was not a senator at the time, but was rumored to be interested in becoming chief of police for a second time. Toussaint served as the interim police chief in the first Aristide government, after the military was disbanded and a new police force was being formed. At the time Dominique was said to be preparing a series of dossiers on the corrupt practices and drug trafficking records of several Lavalas officials, including Toussaint, according to several accounts. Montas, however, insists there were no dossiers. "Jean just accused people in his daily commentaries," she said.

The October editorial was delivered during one of Haiti’s most delicate periods last year. Three months earlier, the U.S. had ended a police training program. Several police officials favored by US trainers, and known not to have close ties to Lavalas, had been forced to resign. The most influential was Robert Manuel, the state secretary for public security, who fled to exile as Lavalas officials, including Toussaint, built a cacophonous campaign against him. "First the graffiti appeared, and he knew he had to get out," said a police source. The editorial was given days after the funeral of Jean Lamy, a reportedly honest army officer and advisor to the national police, who was scheduled to take over Manuel’s post. Dominique decided to write the editorial because Toussaint accused Manuel of the murder, and Dominique understood there was a power struggle inside the police force, with Toussaint pulling to take over key police posts.

The independence of the police has been hailed as one of the underpinnings of the new Haiti. All throughout Haiti’s history the police and the army were used for the capricious whims of whom ever was in power. The new police were supposed to be above politics, but some Lavalas officials were never happy with the US training, according to foreign observers. Dominique was suspicious of U.S. influence but supported the idea of an independent police force, and attacked Toussaint for attempting to carry out his power play. "It is bad strategy," warned Dominique in the editorial. But then he said what many have interpreted as a sign that he knew Toussaint was a tough opponent. "If Toussaint comes after me, I will denounce him publicly and again go into exile with my wife and children."

Toussaint is not the only suspect, and investigators believe the murder was planned by several influential individuals. The judge is still obtaining preliminary testimony from suspects and witnesses believed to have useful information on the case. Some of the individuals who have been questioned by the investigating judge include Jean Claude Nord and Gerard Georges, the two lawyers who threatened Dominique a few days before his murder in a program aired on Radio Liberte, a New York radio station run by former Duvalier allies; Senator Dany Toussaint, who has responded to only one of three subpoenas, and whose lawyer is Jean Claude Nord; Senator Jean Claude Delice, a Lavalas member whose car was seen near the radio station in the early morning when the murder occurred; members of Toussaint’s security force; and two former military officers, Richard "Cha Cha" Salomon and Jacques Aurélus, both close allies of Toussaint, according to investigators.

Six people are in jail suspected of being potential triggermen or accessories to the crime. They have connections to local criminal gangs operating in Port-au-Prince, according to several sources close to the investigation.

The murder was apparently planned during a series of meetings. At one of the meetings, the intellectual authors met with the head of a prominent criminal syndicate. Authorities are very interested in a street thug known as Ronald Cadaver.

Cadaver is a former member of Aristide’s security detail, who allegedly runs a protection racket in downtown Port-au-Prince. Tall, dark and in his 30s, Cadaver is said to be a boss to several gangs with links to drug traffickers, car thieves and other criminal rings, however, his job is merely that of an enforcer.

Information on Cadaver’s activities link him to gangs operating in the seaport of Port-au-Prince, which is located less than a mile from the ruins of the St. Jean Bosco church, Aristide’s former parish. The territory includes the port where boats traveling between Miami and Port-au-Prince dock, and a dusty large central market where vendors congregate to purchase piles of rumpled used clothing they sell around the capital.

According to sources who follow the investigation, the killers arrived at the radio station in three cars. Two parked near the station’s entrance, a third down the street. The first informant to come forward said a white Cherokee and a red Nissan Pathfinder, were the two vehicles used as getaway cars. Extremely expensive in Haiti, one of the vehicles was a rental, investigators said.

Two of the suspected killers are brothers who belong to the notorious Road Nine Gang, which is known to Haitian and international sources as having a specialty in for-hire assassinations. It normally operates downtown, collecting extortion money from merchants, according to investigators. One suspect goes by the name of "Tilou," although his real name is Jamely Milien. His brother is Jean Daniel Jeudi, known as "Gime." Tilou, 23, is a well-known hit man, according to police sources. He told the investigation he is innocent. He has no known source of income, but when he was picked up, police found $4,000 in his possession, and an expensive cell phone.

The third suspect in jail also allegedly works for Cadaver. He is a Haitian who was deported from the United States, under stricter immigration laws that send criminal non-residents back to their countries of origin. Two of the other men in jail are policemen who have connections to influential Lavalas members. One of the policemen, Ralph Leger, had in his possession the white Cherokee used in the murder, according to police sources. Another suspect in prison is said to have been a member of the security force at the Presidential Palace, a place from where several political murders have been carried out, according to international sources.

An alleged top lieutenant of Cadaver was murdered in daylight in late January. Gasoline, as he was known, was apparently passing on information, according to knowledgeable sources.

The first breaks in the investigation came when a man named Philippe Markington decided to talk to the judge. Known around town for selling information for a fee, Markington carried a press card and a police card as identification. Claiming he had coincidentally found himself near the site of the murder at 6 a.m. on April 3, the informant said he saw everything that occurred that day.

But his information was so "sharp" according to sources close to the investigation, that police became suspicious and jailed him as a suspicious member of the assassination team. Police even believe he could have been an alternative hit man. Markington allegedly came forward because he wanted the court to intercede and release some of his friends who were in jail on an unrelated case.

Markington even tried to get the U.S. Embassy involved in the case. He had developed a relationship with the U.S. Embassy’s public affairs office and met several times with PAO officer Dan Whitman. According to a document put together by the Haitian government, Whitman said he had met with the informant because he provided information on attacks against the opposition. Questioned by the IAPA, however, Whitman only said he met with Markington because he represented a civil society organization. Whitman said he did not know if someone was trying to set him up with Markington. According to Whitman, Markington had called him "a number of times" and he had been authorized by his superiors to receive his visits." Whitman said that when he found out Markington was in jail he "expressed his concern for his well being, to him and to Haitian government officials." Whitman said he could not "guess if he was being set up by Markington or people associated with him.

Markington happens to have been irreplaceable for the investigation. Although he denies he knows anything about the case, investigators believe he belongs to the group of suspects. Among some of the early leads Markington provided were the license plate number for the white Cherokee used in the murder. The vehicle led investigators to Jean Wilner Lalanne, the former military man with Lavalas connections who died after the operation on his buttocks. Lalanne was a close associate of Toussaint and a known operator in a car theft ring that brings stolen cars from Miami by boat and sells them in Haiti and in the Dominican Republic. Stolen cars are used to launder drug trafficking proceeds, investigators said.

Suspect Dies

Lalanne was detained in June 2000, but wounded in the buttocks when he attempted to escape. He spent 13 days in Port-au-Prince’s general hospital, refusing treatment because he feared he would be killed to stop him from talking. The day he chose a doctor, one of his lawyers, apparently Ephesien Jeassaint, arranged for Lalanne’s transfer to a private hospital where Alix Charles, an orthopedist, operated on him. Why an orthopedist operated Lalanne was never explained. But when Lalanne died, the doctor panicked and called Montas and the judge on the case. After testifying for the prosecution, he left Haiti for an undisclosed location.

Charles later sent a letter to this reporter in which among other things he said that Lalanne’s lawyer was not Nord, as originally said, but Jeassaint. He also explained that he was not in an undisclosed location but in New York and that he had left Haiti on November 17, 200, and was admitted to Beth Israel Hospital for treatment for a heart ailment. Other remarks by Charles are included at the end of this article.

The initial cause of Lalanne’s death, according to the death certificate was heart attack. Lalanne was 32-years-old at the time of his death and in apparent good health. Later Alix Charles changed his version and told a friend, Pierre Alix Nazon, an urologist and colleague, that Lalanne died of a pulmonary embolism. He claimed Lalanne had a shattered hipbone. Police sources said this is false. The judge charged Charles with involuntary homicide. Knowledgeable sources said Lalanne apparently died from poisoning.

Dany Toussaint

As Dominique’s body laid in the coffin during the funeral ceremony held at the soccer stadium a group of Lavalas supporters approached the coffin and danced suggestively around it, chanting anti-opposition slogans. In the heat of the moment, one of the supporters slipped a picture of Dany Toussaint inside the coffin. One of Dominique’s nephews witnessed the incident and pulled the photo out. The action, however, has puzzled investigators as they have tried to understand its meaning. To some this was a cynical display. Whatever the meaning, it was a macabre gesture.

Toussaint has not kept quiet on the face of attacks and charges on the Dominique murder. He has even accused the widow, Michele Montas of planning the murder. His lawyer Jean Claude Nord, has charged Michele Montas with organizing the attacks against Toussaint, to thwart his chance to run in the 2006 presidential elections.

Today Toussaint is an influential and popular Lavalas leader. Accused by U.S. Cong. Dan Gilman last April as a top drug trafficker in Haiti, Toussaint was elected senator after spending thousands of dollars building soccer fields in Port-au-Prince’s poor neighborhoods—a gesture reminiscent of the late Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar. He received the highest percentage of votes in the legislative elections, drawing on his popularity among young men, who constitute the largest population sector in Haiti.

A former military officer, Toussaint became close to Aristide’s political movement in the early 1990s after claiming he had refused to carry out an order to assassinate the former priest. In 1997, he was arrested by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Washington sources said the intelligence officials, who have enough information on Toussaint did not pass it on in time to INS. Toussaint was released after two weeks.

Elected on a public safety platform, Toussaint promised to be tough on crime, an ironic twist given the rumors about his alleged involvement in drug trafficking. Toussaint’s election to the Senate gives him ample power in Haiti. For one, he has immunity on the Dominique case. Even if the judge found enough evidence to take him before a court of law, the Senate is Lavalas controlled and would never vote to lift Toussaint’s immunity. Already, the Senate has circled the wagons around Toussaint.

Toussaint sent a letter of clarification to this office on March 27, 2001, and this is included at the end of this article.

Note from the Editor

The following is the edited version of the letters sent by Senator Dany Toussaint, Léopold Berlanger and Dr. Alix Charles to the IAPA as a response to the publication of the report written by Ana Arana of the IAPA investigation into the murder of Haitian journalist Jean L. Dominique, director of Radio Haiti Inter.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter to the IAPA from Senator Dany Toussaint:

March 27, 2001Madam,

As some of your Haitian colleagues had said, it is not the advantage of journalists to kill scapegoats, they should only be interested in the punishment of the real guilty perpetrator. But in order to inform your readers, I am going to pick up several inaccuracies and bad opinions in your papers:

How have you been able to claim that the proofs (which ones?) showed that these dignitaries (Lavalas) saw Dominique's sense of honesty and independence as a threat?

- Senator Jean Claude Delice, Lavalas member and one of Toussaint's friends, whose car had been seen not far from the radio station, early in the morning, when the murder occurred (page 10, 2nd paragraph) I only knew Jean Claude Delice's face when he took the oaths at the Senate of the Republic. He is a member of kozepep (a farmer organization) close to Jean Dominique. Jean Wilner Lalanne was not a previous army member so I didn't have any professional or other relationship with him when he was alive.

- "The inquiry recently showed that Dominique was apparently victim of fights coming from Aristide La Fanmi Lavalas´ political party". Just after having said that, "the list of the suspects is long, previous members of Duvalier's dynasty and corrupt business men." Are all these people members of Aristide´s political party?? You don't give us any answer on this point...?

- Toussaint was elected as a senator after having spent thousands of dollars to build football stadiums in poor areas in Port au Prince using the same way as Pablo Escobar. You seem to be so interested in comparing me to Pablo Escobar, that you keep talking nonsense, the Haitian state only built one stadium Silvio Cator, in the whole country, ten years ago. I wonder where are the ones I am supposed to have built with only "thousands of dollars"??

Further, you say: "today Toussaint is a Lavalas popular and powerful Leader." Maybe this is the reason for my recent difficulties.

In 1986, I ran away from my country in order to avoid murdering democratic leaders like journalists and priests. In 1991 by risking my life in defense of President Aristide during the coup d'etat, I became suspicious among Haitian and even foreign politicians. Why should I be the only military leader to be sued?? Why is it the only one who went twice into exile???

Dany Toussaint

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter from Dr. Alix Charles

March 2001

Mrs. Ana Arana

Inter American Press Association

Madam,

As for your information, I must give some necessary rectifications to this article, which is prejudicial to my person.

Lalanne had really been admitted in the general hospital for thirteen days but because of the three bullet wounds in his left buttock, which had caused a fracture of the superior part of his left thigh that was not cured during those thirteen days. His lawyer Mr. Ephesien Jeassaint has contacted me to make an intervention on his fractured thigh.

Let me tell you that the femur fracture must be operated on as soon as possible to prevent any pulmonary embolism that comes with it. Any medical paper concerning Mr. Lalanne as well as the X-Rays done before and after the sick man´s death, claiming the diagnostics are in the hands of the Justice. I did not have the opportunity to talk to Mrs. Montas but do make a little effort call her and ask her any questions about that.

I did not have to call the judge; he called me three days later and told me to come to his office with the lawyer of Radio Haiti, Mr. Mario Joseph and a Police officer.

I left Haiti on November 17th to come to the US and not to an unknown destination, because of heart problems, and I had been admitted in Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

It was never said that Mr. Lalanne had any heart attack as it was said in the report I made the day of the death. Do you know that I wrote the death report with the diagnostic of heart-pulmonary stop probably provoked by a pulmonary embolism?

Don´t you want to look for the original of the heart attack diagnostic? I had the opportunity to explain, on July 1st, to the investigating judge who wrote it down on his report. He also has a copy of the medical report. My lawyer is another Mr. Georges.

You will be able to find it by a simple verification, I never had to say anything else; it has always been a pulmonary embolism.

Mr. Lalanne truly died from a pulmonary embolism due to his 13 day-old fracture. He had the privilege to have his autopsy done by Dr. Rodrigue Dazang, 5 days after his death. The corpse would have disappeared 3 months later, according to the judge. There were no human manipulations concerning the death while in the hands of the 2 experienced anesthesiologists Dr. Ivose Chrysostome and Dr. Gina Georges and in front of my assistant Dr. Delano Benjamin.

Dr. Alix Charles

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Letter from Léopold Berlanger

March 16, 2001.

The purpose of this letter is also to draw attention, to phrasing in your story that might suggest to readers that my name "surfaced" in this matter, because, and I quote: "initially Lavalas strongly pushed forth the theory that Dominique could have been killed by former Duvalier followers." I take particular exception to that insinuation, inadvertent as it may be, because of how strongly I have always felt in my opposition to the Duvalier regimes.

In January 2000, I was elected head of the Council of National Observers (CNO) an organization mandated by the electoral law, which incorporates various sectors of different political horizons, including Lavalas. This involvement is one of the latest in my efforts to advance the cause of democracy in my country.

The CNO whose mission is to ensure the participation of competent and indigenous election observers, also includes prominent human rights organizations like Justice and Peace of the Catholic Church, the Haitian Platform of Human Rights Organizations (POHDH) and peasants organizations like Koze Pèp, that originated within Lavalas.

The bogus assertion that the CNO and myself were in any way connected with Dominique's murder can be traced back to parties who have by their actions consistently exhibited contempt for the democratic process and the rule of law. Associating me in any way with the Duvalier regime is equally offensive.

Léopold Berlanger

|