April 20, 2000

Case: Pablo Pineda Gaucín

|

Few people were surprised by the murder of journalist Pablo Pineda.:

April 20, 2000

Alejandra Xanic (URR-SIP)

Few people were surprised by the murder of journalist Pablo Pineda. Police officers, fellow reporters, local newspaper editors and his own family knew it was going to happen one day. "Watch out, Pineda!" his wife, Rosi Solís, used to hear whenever they went for a walk together.

Others because they were shocked at the crude and uninhibited pictures that he used to publish every day in the La Opinión newspaper. "He went overboard; that guy was heartless," says Carlos Gómez, who shines shoes in the market and always has a newspaper on hand for his customers. Photographs of people who have been run over, suicides, drug dealers, officials he labeled as corrupt, rapists, rape victims.

Yet others because they were convinced that the 39-year-old journalist rubbed shoulders with organized crime in this border town. Either because they didn’t believe how someone with a journalist’s salary could live as well as he did or because they read the frequent reports about him in other publications – "Pineda the drug-trafficker" screamed a headline in the afternoon paper El Imparcial. "He was not all there, he looked for it," says an editor at La Opinión newspaper, where Pineda had worked for the past eight months.

Pablo Pineda Gaucín was a man of contrasts. Generous and tyrannical. Loyal and vengeful. As a journalist he was also judge and jury. He was found dead on Sunday, April 9, 2000, by agents of the United States Border Patrol. His body, bound hand and foot, was wrapped in a sleeping bag, the head covered with a plastic bag, with a 9mm bullet wound to the back of the neck. "The killing bore all the hallmarks of the drug traffickers ," said the sheriff of Brownsville, Texas, Omar Lucio, who led the initial investigation.

Pineda’s body arrived on Matamoros Monday (April 17) and was buried right away. One week later, no one has called for an investigation into the murder.

On the trail of Pineda

Crime reporter Martín Castillo was one of the last people to see him alive. They were at the police precinct two doors away from the La Opinión newspaper offices on the night beat the evening of Saturday, April 8. Pineda answered a call on his cellular phone, seemingly from someone he knew. He told Martín he would be back later, saying he still had to deliver some photos to the paper, and he drove off in his 1992 Grand Marquis.

Someone else saw him around 11:00 p.m. that night in the Ramírez district covering a police shakedown, his wife, Rosi, learned. "It could be that, because it was a sparsely-populated area and the road was dark, someone followed him or ambushed him," she believes. He had arranged to take her out to dinner that evening, but he did not turn up.

At 2:30 a.m. on Sunday, two Border Patrol agents patrolling a section of the border noticed that two cars parked on the Mexican bank of the Río Grande river and three shadowy figures took a large bag out of one of the vehicles and carried it on their shoulders across the river bed. Convinced that this was a drug delivery and someone would come to collect it , they decided to wait and see. The shadowy figures dumped the bag on the U.S. side of the border and went back to the Mexican side. At 6:30 a.m. the agents discovered that it was a body.

According to Sheriff Lucio, the murderers took the body to the U.S. side of the border to complicate the investigations, thinking they would not be detected. It is not the first time that has happened – some years ago the bodies of two agents from the Mexican Attorney General’s Office were found there. "We know the murder was not committed her (in the United States), but in Mexico and that’s where they have to investigate," Lucio said. Several newspapers reported that Pineda’s body showed signs he had been tortured, something that Lucio could not confirm. Crime reporter Castillo reported that the call to Pineda’s cellular phone could not be traced – it had been made from a public call box – so the trail went cold.

Not the first time

Pineda had been the victim of attacks before. As arrived at his home in the Valle Alto residential district on the evening of October 20, 1999, a man shot at him. Nine bullets lodged in the walls of the house and his car. Pineda escaped unhurt. He said he remembered perfectly the face of the man who had shot at him and was convinced that alleged drug trafficker Roberto Torres Torres, a.k.a. "El Muertero" (the hit man), had ordered the attack. "He thought they were going after him because of what he published," said his wife, Rosi – a reference to photos of Torres’ earlier arrest.

Shortly after the attempt on his life, Pineda went to the hospital where Torres was being treated under police custody and went at him tooth and nail. "He pulled out his tubes and all, and threatened him," a colleague recalls. Two days later, Héctor Fernando Torres de la Garza, nicknamed "El Chachis," the young gunman that Pineda claimed had shot at him, was found dead in a shopping mall parking garage. In Matamoros the rumor spread, and was picked up by local newspapers, that it was Pineda that had him killed. But Pineda was not interrogated and three other people were blamed for the slaying.

Three years earlier, he was attacked outside the Lozano funeral parlor – where last week his body lay prior to burial. A couple of unidentified people armed with sticks set upon him. He had also received telephoned threats.

"Whenever we went out on the street, people would tell him, ‘Watch out, Pineda!’ I got used to that," said his wife, Rosi, a quiet-spoken woman. "Ever since the attack on him he was a changed man. He looked after me. At night he would go down on his knees and kiss my feet and ask forgiveness. He told me to let my children do what they wanted, saying ‘don’t cut their wings and if they choose a wrong path, support them anyway.’ He no longer abused me, we didn’t fight any more. He’d say, ‘No more quarrels, in case I don’t come back today.’ Pablo was sure something was going to happen to him and he was preparing me for it all along." After the October attack, Pineda changed his daily routine to spend more time with his wife and his three children and made funeral arrangements.

"This is a small town, you can’t do anything without everybody knowing about it," says a copy editor at the El Bravo newspaper, who is convinced that Pineda was dishonest. "How do they kill journalists? They do it in a public place, in broad daylight, usually outside the newspaper offices," says the editor of a local newspaper where Pineda once worked and from which he was fired, so it is said, on suspicion of theft and taking bribes. "He was killed like the drug traffickers kill each other."

"He used to tell me, ‘I’m no saint, and just as there are those that love me, there are those that hate me,’" Rosi said. A box stuffed with photos of her husband sits on a desk in the office he had at their home. On a bookshelf alongside a couple of books about journalism and a dictionary are two photographs, one of a round-faced, smiling Pineda, on his fingers the four big gold rings that were found on his body, clutching a high-powered rifle, the other of Pineda firing a handgun at range. "I had them framed. He didn’t know how to shoot, but they were photos that he liked."

Light and shade

Just how true his public notoriety was is not at all clear. Many colleagues and officials knew of Pineda’s alleged links with drug trafficking and smuggling of illegal emigrants only from the stories written by other journalists, as controversial as he was.

According to the authorities, Pineda’s criminal record was clean. "We haven o record of this person ever having been involved in people smuggling," says Carlos Flores González, director of the Interior Ministry’s Migrant Protection Office. "We heard that he was involved in the traffic, that was what was said, but for us he was no suspect we needed to investigate," adds Ramiro de Anda, spokesman for the U.S. Border Patrol in McAllen, Texas. According to Sheriff Omar Lucio, his record in the United States is also clean. Criminal records of citizens are not kept at either the state attorney’s office or federal attorney general’s office, but the respective officials there do not recall ever having investigated Pineda for any suspected criminal activity.

In Matamoros it is difficult not to have dealings with organized crime. Although it has grown, it is still a small town with narrow streets. The local mafia bosses send their children to school there, they take their families to local restaurants, they drive their cars to the same car wash and they frequent the same movie theaters and shopping malls as everyone else.

In addition, the history of the barren desert town of Matamoros and its people is a rough and ready one, linked to gambling and smuggling, of wine during the American Prohibition era, of arms during the Revolution and for the past couple of decades of drugs and people. It is the home of Juan N. Guerra, now an old man confined to a wheelchair but who for many years ran the town from a round table at his downtown Piedras Negras restaurant. He was a northern Mexican version of "The Godfather" – overlord of many drug traffickers, uncle of Juan García Ábrego, one of the most powerful mafia bosses in the country, now serving time in a U.S. prison. "this was a good school for drug traffickers, it’s just that at one time that was seen as no bad thing," says a local historian who, like so many others here, is afraid of giving his name. "It is hard not to rub shoulders with them, not to have some kind of relationship. The only thing you have to do is not get involved," says the editor of a local newspaper.

Feeding the rumors

The Monday, April 10 editorial in La Opinión sings the praises of Pineda. "He was not afraid to denounce official corruption (…and once) dodged the murderous bullets of those who are enemies of the independent press and the truth." But inside the newspaper not everyone agrees. There are those who have tried to convince the owner that Pineda’s is a battle that should not be fought.

Pablo Pineda is remembered as an impulsive person, as generous and vengeful and cruel. He was a Robin Hood and a tyrant, as his wife tells it. "He was a pseudo-journalist," is how Gonzalo Guerrero of the federal prosecutor’s office describes him. "He went so far as to beat up on one agent and some say he threatened to hit them with his camera," Guerrero said.

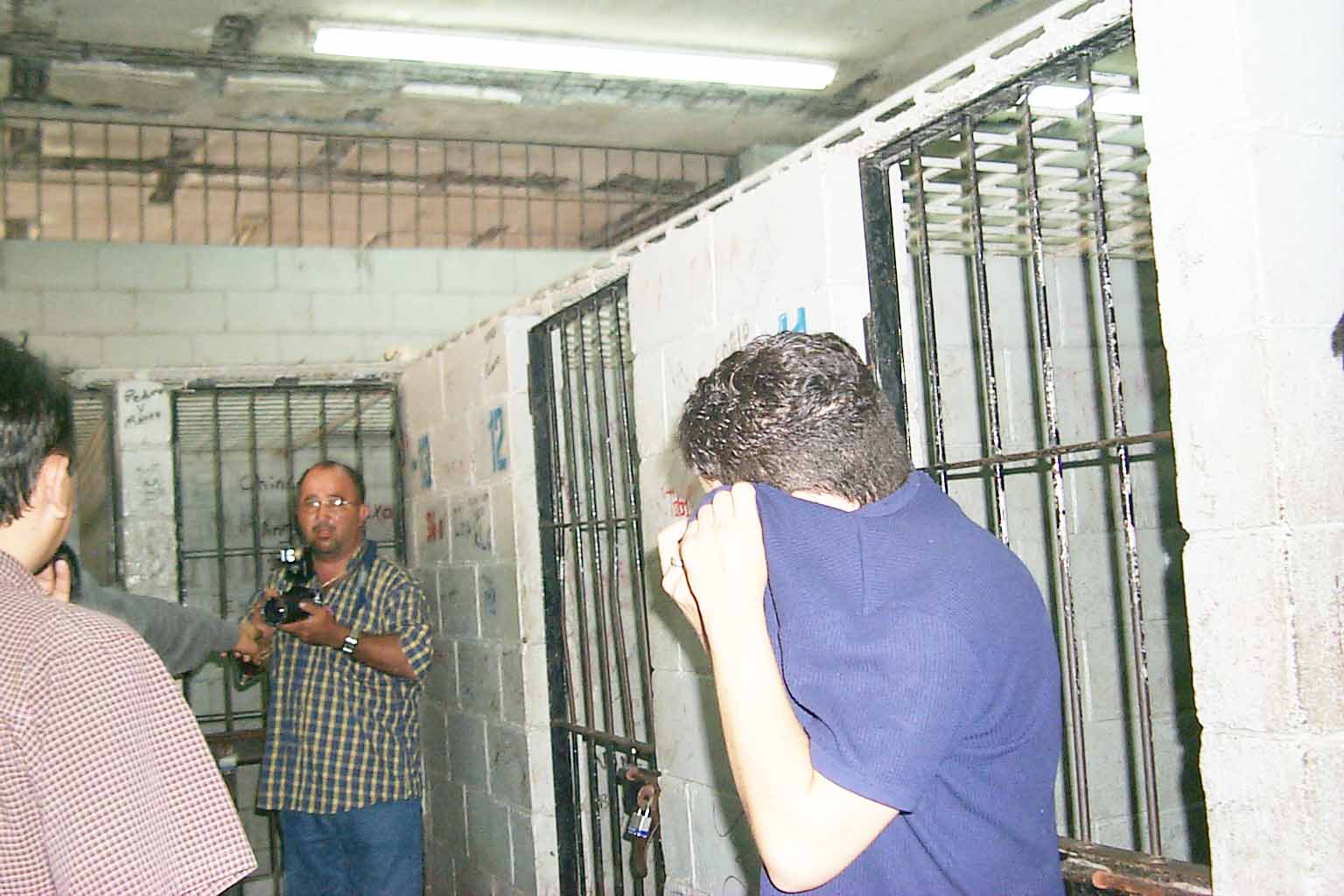

He came to the defense of arrested people, attempting to spring them from jail. He was generous with the windshield washer children at stop lights. Every week he would give 200 or 300 pesos to the family of someone in prison and to a man in a wheelchair begging on a downtown street corner. Pineda had taken the photos the day the man was run over by a train and lost his legs.

"What they say about him is said out of envy," asserts reporter Martín Castillo.

His lifestyle is perhaps what raised eyebrows most and made people suspicious of him. "I don’t know who he got involved with, but nobody who works as a reporter here can afford to live in Valle Alto and run around in new automobiles. He used to come in a Pathfinder SUV and four Mexican-made luxury cars. Just three years ago he was living in a government-subsidized apartment," said a local newspaper editor who asked to remain anonymous. A staffer at La Opinión confided that Pineda used to hand out money to reporters form various media. "They would come here to the newsroom and he gave them money, I suppose in exchange for their not writing against certain people," he said.

"Nobody can live like he did on a reporter’s salary," says a colleague of his at La Opinión. He earned at most 80 pesos at a day at the paper. Just his cellular phone bill ran to 200 to 300 pesos a day, according to figures obtained from the telephone company.

Pablo Pineda nevertheless managed to buy a home in an upscale residential district inhabited by the wealthy and drug traffickers. But the house he bought is a small, simply furnished one. His Grand Marquis and two Crown Victoria cars, all eight years old, and his brand-new Pathfinder are parked on the street.

Pineda had no other job but according to his wife he sold advertising for the paper to the police department and received a commission. On the day of the 28th anniversary of the founding of La Opinión the only full-page message of congratulations was from the police department, which he and Martín Castillo covered. His wife showed a blue receipt for March for 500 pesos, another for nearly 1,000 pesos for the previous month.

In addition, from time to time he sold scrap metal and used cars. "He was a fighter, a hard worker," his wife, Rosi, said, adding that the latest bank statement to arrive at their home showed a balance of 353 dollars n his checking account. "He gave the appearance to everybody that he earned a lot and spent even more. I don’t know if he had other bank accounts or if they saw it all wrong. As the money came in, he liked to spend it, dress well and for me to make myself look good, go to nice places. But he didn’t have a lot," his wife confided. She thinks that now she will turn to selling clothes and setting up a food stand. "He showed me how to survive," she said.

Reasons for his death

His newspaper and television reporter colleagues do not believe he was killed because of his work, his photographs or the stories he wrote. He had begun to write for the paper only recently and when he did so he shared the byline with Martín Castillo. "If it was because of his work, why didn’t they kill me, too?" one worried reporter asked.

The photos and stories he wrote in recent months had not recurring target. His latest works were a series of pictures of the fatal lynching of a police officer by students and his subsequent burial. The incident had occurred a week earlier at the Matamoros Technological College. Police had gone into the college and in a clash with students one officer was beaten and killed. "That was what Pineda was like, he got involved. He was not just a reporter looking at what was going on, taking notes, taking photographs – he jumped into the fight." He tried in vain to rescue the police officer, who died in the patrol car shortly afterwards. "We just hope that divine justice will prevail, because nothing can be expected of earthly justice," he wrote in the next day’s paper.

He also followed up a domestic dispute over a reported extra-marital affair, publishing photos of Eugenio Guadalupe Rivera Mata, a.k.a. "El Gordo Mata" (Fat Man Mata), who allegedly sold drugs to school students, and his accomplices.

The shadowy aspects of Pineda’s life and work are many. "I can’t say he was a saint, I won’t put my hands to the fire for him, because I wasn’t with him 24 hours a day," his wife of 16 years says calmly. "I don’t know if he had any direct dealing with drug traffickers – probably at night when he didn’t come home to sleep he had something to do with those kinds of people, but I can’t either deny it or confirm it. What I can say is that he was no drug addict, as some people claim. If he had anything to do with those people, he certainly know how to hide it, or I was a fool and never realized it," added his 16-year-old daughter.

Pineda was a native of Torreón, he studied accounting and for many years was a "fixer" in government offices in Matamoros, then worked as what is known locally as a "coyote" (literally prairie wolf), providing tags for illegally imported automobiles in league with corrupt officials. "He earned good money at that time, he knew how to win people over, he was very astute," his wife smiles. At the invitation of a friend, he started work as a photographer at the local newspaper El Imparcial. He always covered the police beat and invariably was the first on the scene of accidents and crimes.

Investigation on hold

Pineda’s body was returned to Mexico after an autopsy on April 10. The family of friends provided a tomb for his burial at the Jardín cemetery, the only private burial ground in the city, where relatives of drug trafficker Juan García Ábrego and well-to-do local citizens are also interred.

Along with the body, the Brownsville sheriff hopes to be able to turn the whole investigation over to the Mexican government. "They wanted to make it look like the murder occurred here (in the United States) but we know, because the agents saw it, that the crime was committed on Mexico and we have nothing to investigate," Sheriff Lucio said.

The authorities have made few inquiries since the murder. According to Lucio, officials in Texas took statements from the Border Patrol agents and carried out a post mortem examination. Police in Mexico hunted for the Grand Marquis that Pineda had been driving that night and whose whereabouts remain unknown. They found no eye-witnesses on the Mexican side of the border who could provide any useful information. Headlines in La Opinión declare that the investigation has come to a halt.

Pineda’s newspaper colleagues do not dare to voice their suspicions. "In this town you don’t name names," says a crime reporter from the afternoon paper PM.

"I don’t know what to think. They tell me he had a lot of enemies because of his work and because of his character. He didn’t know how to keep his cool. I don’t know, perhaps someone he had humiliated…," his wife says.

Although under Mexican law homicides are investigated even if no formal complaints are filed, the police department says it has gone as far as it can. "We are inquiring into the incident, but no one has formally called for an investigation, not even the family. Let’s see what happens" says Sergio Puig Canales, the Matamoros police chief.

Pineda’s wife Rosi is determined that there should be no investigation. "Pablo grabbed me one day and said, ‘If anything happens to me, don’t go to the police, because they’ll never pay any attention to you.’ And I asked him, ‘Why do you say that?’ He said, ‘I have upset a lot of people. Just rely on God and divine justice and don’t do anything at the prosecutor’s office.’ He told me that on six occasions. I don’t hold any grudge against the murderers. I just hope that God has mercy on them."

Pablo Pineda is not the first journalist to be murdered in Matamoros. In the 1980s Ernesto Flores and Norma Moreno Figueroa were also slain. Their case has never been solved.

|