April 26, 2006

Case: Benito Ramón Jara

|

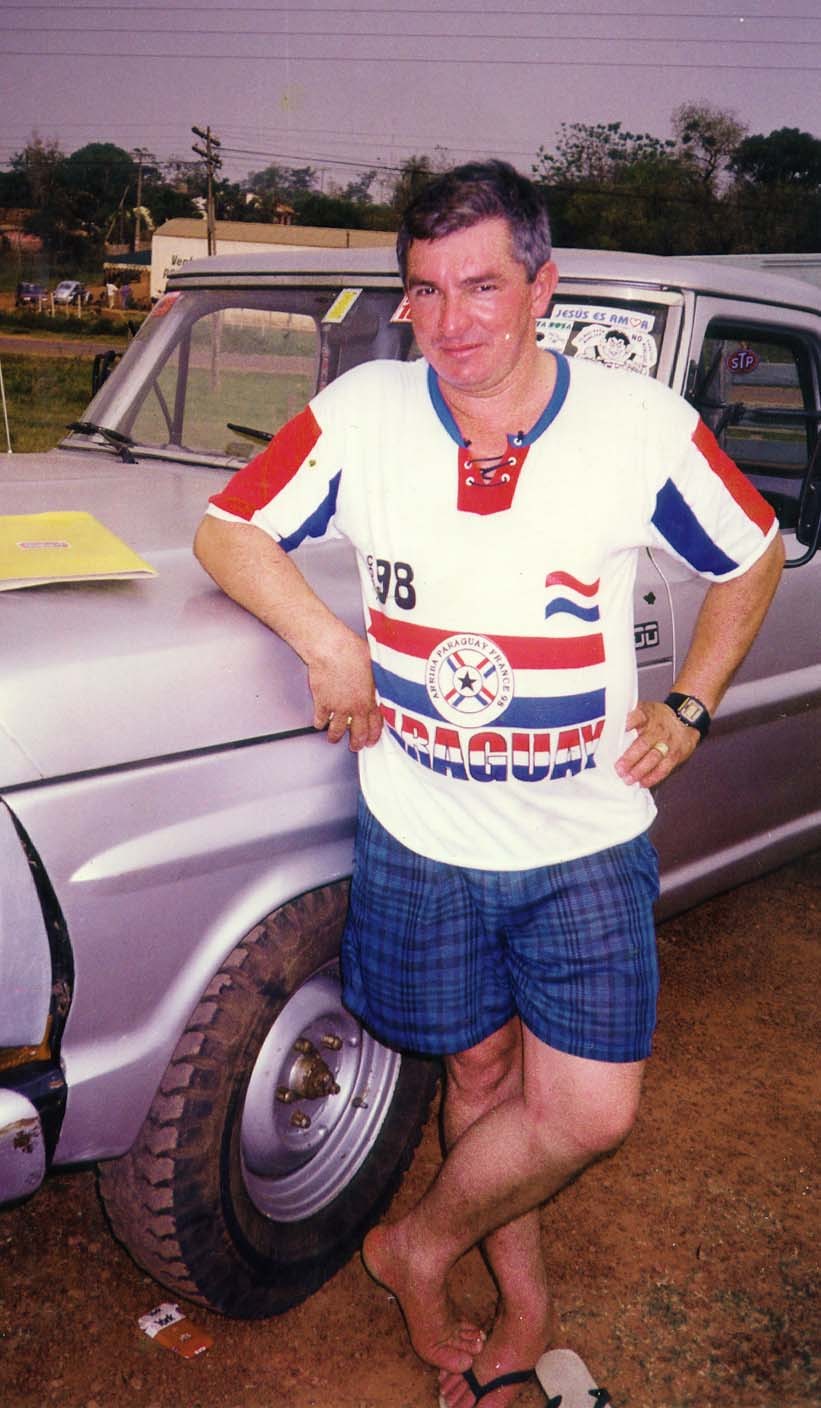

At the roadside:

April 20, 2000

Jorge Elías

If Benito Ramón Jara had not been a contributor in the last year of his life to Radio Yby Yaú, providing news and ads, his death might well have gone practically unnoticed. As unnoticed, perhaps, as some of those appalling crimes that often occur in silence in the northern Paraguay no-man’s land – or really the land of the drug barons and automobile smugglers, of organized crime leaders and villains of all kinds – those who., according to one local resident, shoot first and ask questions later.

It is known as the dry border, with no flags to show whether it is really part of Paraguay or Brazil. It is difficult to be a journalist, or just to live, under those conditions – difficult and dangerous, warns the director of Radio Yby Yaú, Carlos Escobar, an Evangelical minister who admits that the word of God cannot end the violence. Neither the word of God nor the law, in fact. The police, according to Lieut. Reynaldo Vargas, lacks sufficient resources and personnel to cover such a vast, sparsely-populated region of mostly wooden shacks beside the red earth roads that zigzag through the grazing land.

Jara’s body appeared on the side of one such road, leading to General Bernardino Caballero township, some 12 miles from Yby Yaú, between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m. on Thursday, April 13, 2000. Jara, 37, had been shot six times – once in the face, once in the head, once in the chest and three times in the stomach. He had been riding a motorcycle he owned, later found abandoned (presumably by his killers) some 1,000 yards away.

A settling of old scores? Jara’s second wife, Victoria Jara (her maiden name was the same as her married name, but they were not related), says her husband had received threats – from his first wife, living in nearby Sapucai township, and from a neighbor of his in Paso Jhú who, like Jara, drove a passenger bus between the two towns. "They killed him out of envy, because he had a full-time job," Victoria sobs as she suckles Víctor Ramón, her 30-day-old baby who will now never get to know his father.

Jara was not killed because of his relationship with the radio station. "He was a good man, friendly to everybody, who never dealt with any information that could put him in any kind of trouble," Escobar says. Lieut. Vargas agrees. "He was no journalist. He was a stringer for them and nothing more. He didn’t even have a press pass."

Disturbing background

Jara’s work for the radio was sporadic, just a way of his field of action as a bus driver and grocery store clerk. The day he did, he was delivering cheese to General Bernardino Caballero, a town famous for its Brazilian-origin population.

The Portuguese language influence is so great in northern Paraguay that it is often mixed with Spanish and the local language, Guaraní, to make a distinctive local dialect, which seems to reflect the character of those speaking it – tightlipped, introverted, distrustful of outsiders, even those from the capital, Asunción, some 280 miles away.

Violence, however, shortens distances. The fruit, perhaps, of the undemocratic way of life during the 35 years’ Stroessner dictatorship and which erupted like a dormant volcano with the assassination of Paraguay Vice President Luis María Argaña on March 23, 1999. Facing indictment for that crime, the first of that magnitude, President Raúl Cubas Grau sought asylum in Brazil, where Stroessner now lives, and Gen. Lino Oviedo, facing 10 years’ imprisonment for his failed attempt to overthrow President Juan Carlos Wasmosy in April 1996, went into hiding one day before Argentina’s President Carlos Menem ended his second term in office, thus making a mockery of the asylum he had been granted in Argentina. Only three suspects, all low level, have been brought to trial in the assassination of Argaña, which threatened to topple Paraguay’s institutions.

It seems to be in vain, therefore, that the Paraguayan Journalists Union (SPP) has called on the Interior Ministry to solve the Jara murder case. And similarly useless would appear to be the insistence on bringing to justice those guilty of the murder of Santiago Leguizamón, a reporter who wound up shot to death because of what he exposed in Pedro Juan Caballero township, near Yby Yaú, on April 26, 1991 – Journalists Day in Paraguay. He owned Radio Mburucuyá and contributed to Radio Ñandutí, Channel 13 TV and the daily newspaper Noticias, all in Asunción.

"We don’t have many details about Jara," says Julio Benegas the SPP’s secretary general. "He was little known, in not unknown, and was not among our members. The police are investigating if it was a crime of passion or he was killed because he owed money. But, because he died in the same geographical area, we remember Leguizamón’s murder. That was a gag for everybody."

Conflict resolution

Jara was killed the same way as Leguizamón had been for his exposure of corruption, drug trafficking and smuggling – he was riddled with bullets. "There were 40 shots, " reports Daniel Piris, an AP photographer and president of the Paraguayan News Photographers Association. "That hit people hard because Stroessner had been overthrown barely two years before and we were beginning to live as a democracy."

That the two incidents occurred in the same area would seem to indicate a modus operandi that does not distinguish between journalists and non-journalists – either things are settled this way (by the bullet) or they don’t get resolved.

A monument to Leguizamón stands in downtown Asunción as a symbol of freedom of expression following his death at the age of 41. "Not long ago they killed Nilo Vázquez, a really dangerous guy who grew marijuana and went after journalists," says Escobar, who has spent nine years running Radio Yby Yaú, "He could be the murderer, but others who deal in drugs and so on also could have done it. I very much doubt that this crime will ever be solved."

Is it so dangerous to be a journalist on the Paraguay-Brazil border? It has been for Cándido Figueredo, correspondent of the Asunción daily ABC Color, who almost died when his home was machine-gunned, Escobar recalls. "Yes, it really is difficult to be work. Especially if one doesn’t hide anything or take bribes," he said. "The politicians don’t do anything."

In the Paraguayan power structure the Colorado Party holds most of the cards. Since Stroessner’s ouster on the night of February 2, 1989, the party has kept on going, a dinosaur that resists extinction, setting a record for survival, since 1954, surpassed only by Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which has stayed in power for seven decades.

The death of Jara, who was born and raised on the outskirts of Asunción, is just another crime in an area that seems to be used to violence. "We have engaged in cases of all kinds," says Ceferino Soria, an official in the district attorney’s office in Yby Yaú. "I am talking about deaths and injuries for various reasons, whether arguments, drunken brawls, settling of old scores, smuggling, drug trafficking." Or whatever.

"There is no justice"

Yby Yaú is Guaraní for "eat earth." There does not seem to be a lot of difference between eating earth and biting the dust. And that seems to be the sentence if you step beyond the mark. Jara’s second wife says he had recently got into debt and his first wife (with whom he had three children – a boy of 7, another 9 and a girl of 12) was hounding him. "He liked to work at the radio station, but he never received any threats because of that," she said.

At her home, located on the road from Asunción to Pedro Juan Caballero, a number of boxes of onions indicates that she sells vegetables and groceries. She survives that way while the blue Chevrolet bus stays parked nearby. Across the road, a group of neighbors has gathered to pray for Jara’s soul. They call for justice for Benito Ramón.

Justice that Virginia González, a friend of the family, did by paying him up to the last cent of what she owed him before he died. "You know why?" she asks. "Because that’s all the justice there is. If you don’t have a rich or powerful relative, you can’t expect justice." It is a widely-held view, not only in Paraguay but throughout Latin America – except that in some cases the good pay as sinners, while the real sinners, as has happened in the case of journalists and non-journalists killed by thugs, go free.

Jara certainly had no money on him nor anything of value when he died, leaving two widows and four orphans. His first wife went to the funeral on her own – the three children he had with her were not there, according to his second wife. The same was true of Jara’s 26 brothers living all over the country who would not have learned of his death if he had not been working for the radio station, although all of them separate the wheat from the chaff – that is, personal matters from public affairs. In any event, they remained at the roadside.

|