July 29, 2001

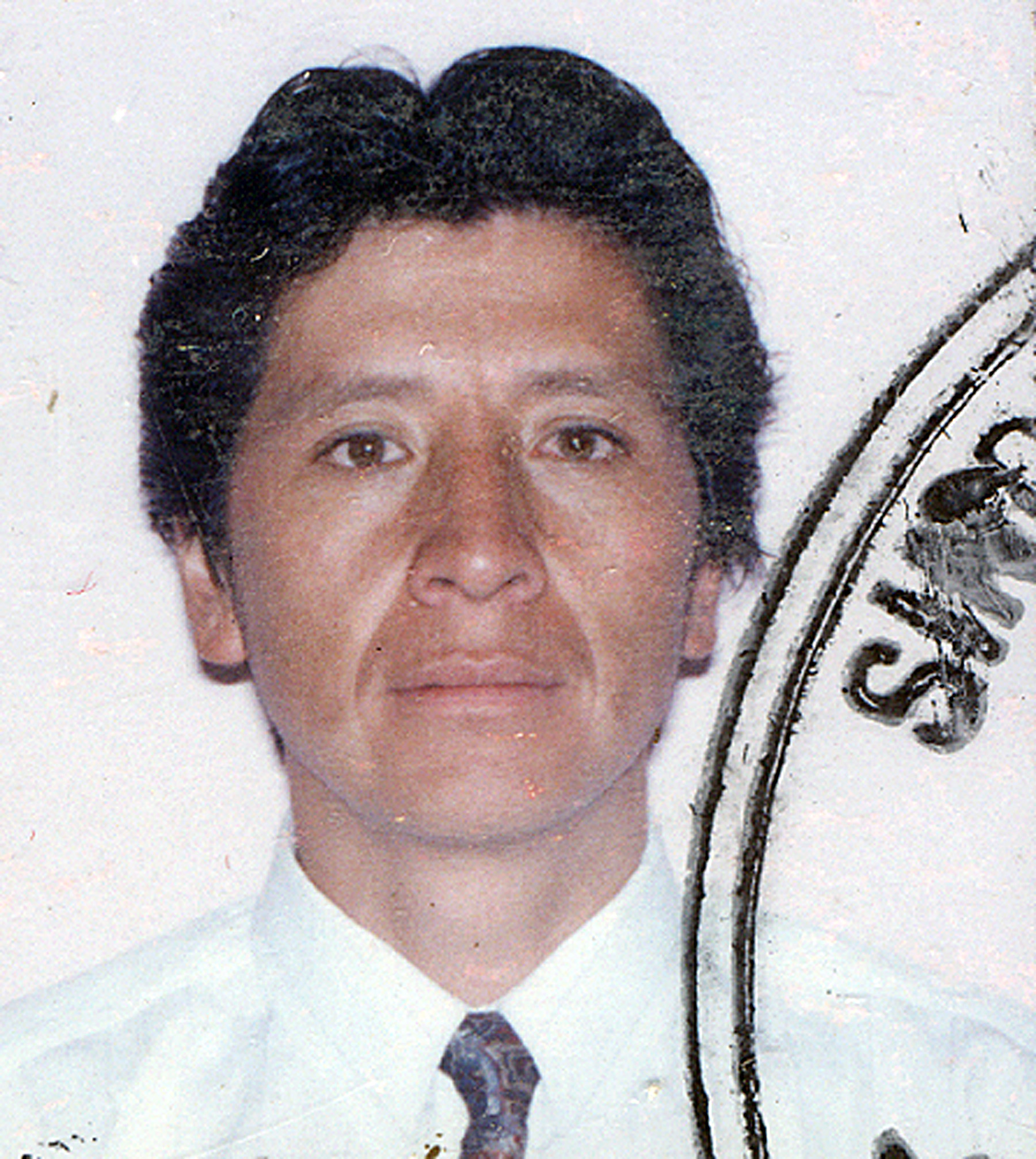

Case: Juan Carlos Encinas

|

A thorn in the side:

July 29, 2001

Jorge Elías

From the mountaintop, the world revolves down below as the gusts of wind blow harder. A sudden dizziness, cold sweat, a humming in the ears - all symptoms of mountain sickness that all foreigners feel in Bolivia. Here, more than 13,000 feet above sea level, one can see far off, following the brown pointing finger, a distant field near a water tank where Juan Carlos Encinas fell on Sunday, July 29. He was the first journalist in Bolivia to be murdered in years.

Was he the right journalist in the wrong place, or the wrong journalist in the right place? Just a journalist, apparently not on assignment, carrying a camera and a portable tape recorder in the midst of a tumult of shots and rocks. He was felled by one shot, waiting for help that came too late.

The people of Catavi, in the province of Los Andes, some 32 miles from the Bolivian capital of La Paz, were attempting to defend themselves from an invasion of 50 to 60 armed people, they said. It was early on Sunday, the sun was just coming up. Encinas, shot in the lower abdomen according to a forensic report, was surrounded by nine spent caliber 9 rounds that police gathered up as evidence.

Another bullet pierced the arm of Juan Mario Ticona Limachi, a local resident. The sight of blood apparently turned the attackers' rage into fear and they immediately fled in the buses in which they had arrived to Catavi over a dirt road rutted by trucks coming and going.

Encinas, doubled over in pain, according to another local resident, Manuel Quiñajo Mamani, had to wait from 6:30 or 7:00 in the morning until after 10:00 to be taken to the San Martín de Porres clinic in El Alto, 12 miles from La Paz. "But he died from internal hemorrhage and loss of blood," says his brother-in-law, René Falcón. First aid - serum and oxygen - that he was given en route to the clinic failed to save him.

Why was Encinas in Catavi? His wife, Betty Falcón, was a ember of the Catavi Multiactive Cooperative Limited, which for a long time has held the concession for exploitation of limestone deposits. The town of 208 inhabitants lives off the sale to a cement company. It is a humble township, with small, windowless houses and an empty central square. It is just a few blocks on the road to El Alto. It's the poorest town in Latin America, according to Mauricio Carrasco Ayala, the managing editor of the La Paz daily newspaper El Diario.

Far from peace

The wife of Feliciano Ticona Mamani, one of the oldest men in Catavi, has been crying since then. She only sleeps during the day and at night she thinks that the people who killed Encinas and wounded Juan Mario Ticona Limachi will come back. Ticona, speaking a little Spanish mixed with the local language, Aymara, says that they shot at them with revolvers, 9mm caliber, as stated in the police report.

"We are peasants and we are not protected," says Marcelo Huaipa.

They are in Catavi, just a few steps from La Paz. But in fact they are many miles from the peace for which the Bolivian capital is named. Since the death of Encinas, a popular reporter, a freelance stringer for television news programs and a radio program, they have been waiting for another attack by a group that, they say, is trying to take away their livelihood - the exploitation of the limestone deposits in the hills.

The conflict, in which the National Cooperatives Institute, a dependency of the Ministry of Labor, is mediating, has been going on for three years. Encinas, 39, was on the side of the Catavi residents, those who, like his wife, belong to the Multiactive Cooperative. When Sunday came, they knew they were going to be attacked by the same people that a year earlier, on July 5, 2000, had smashed Encina's camera as he covered the clash, in the midst of another gunbattle, for the La Paz Canal 21 television news program "Enlace."

This time, his situation was - or seemed to be - different. "I think he had taken sides because of his wife's role," suggests Ramiro Linares, production chief of Canal 24 television in El Alto. Encinas was not on the staff, but a stringer for the program "Impacto Informativo" (News Impact) and well as for Radio Libertad radio station's "Tiempo Nuevo" (New Times). He was also involved with the Press Workers Union in El Alto. Most of them there remember him as a good friend, affable, of a happy disposition and optimistic outlook.

Following the clashes, El Alto Criminal Court Judge Alfredo Jaimes, at the behest of District Attorney Waldo López Paiva, issued a warrant for the arrest of eight people, who were later freed on bail and subsequently re-arrested. They were Edgar Mamani Limachi. Julio Limachi Mamani, Eugenio Limachi Mamani, Félix Loza Mamani, Teodoro Limachi Mamani, Juan Laruta Quispe, Agustín Mata Condori and Juan Francisco Limachi Quispe. Despite similar names, they are not related to each other.

"I am a cautious judge," Jaimes said. "I do not know if the journalist was covering a story. The suspects were freed on bail under terms of Article 16 of the National Constitution and Article 6 of the new Criminal Procedure Code, which presume innocence until proven guilty. The defense submitted a series of documents, such as power and water bills and marriage certificates, proving they are residents of La Paz. There was no obligation to do so."

Only District Attorney López Paiva has the power to order an arrest. The judge, he explains, cannot do so unsolicited. The investigation initially has a six-month deadline. Among those suspected of firing the weapons are two Bolivian Air Force sergeants, Renato Limachi Ticona, 22, and Humberto Alvaro Quispe Limachi, 23 - in this case cousins - who were billeted at Santa Cruz de la Selva, some 310 miles from La Paz, and the El Alto Base, respectively.

"This is outrageous, an irresponsible action that is designed to discredit our institution," said Colonel Víctor Maldonado Guzmán, the Air Force public relations director. "Those guys still have their guns boxed up, as they came from the factory. They have not used them. A 9mm caliber revolver is not necessarily a military weapon - anyone can obtain one on the street."

Trophy of war

It is common among the country people in the Andes, according to Roberto de la Cruz, a reporter for El Diario, for drafted soldiers to return home with a trophy of war, usually a stolen gun, as a testimony of his having done military service. Two Mauser rifles had been confiscated prior to the July 29 battle from among the people who attacked the Catavi cooperative members.

Bolivia has been beset lately by peasant and miner demonstrations demanding greater attention by the government. Former dictator Hugo Banzer, suffering from cancer, resigned as president and on August 7 Vice President Jorge Quiroga succeeded him.

Inter American Press Association President Danilo Arbilla, editor of the Montevideo, Uruguay, news weekly Búsqueda, meanwhile has declared a "state of alert" in light of the escalation of violence being unleashed against journalists in Latin America. So far this year alone, with the murder of Encinas and of Mário Almeida Filho of Brazil, the death toll amounts to 13 - seven in Colombia, two in Mexico and one each in Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica and Paraguay. This caused IAPA Impunity Committee Chairman Alberto Ibargüen, publisher of The Miami Herald, Miami, Florida, to call on governments in the hemisphere to take steps to solve the crimes and bring the guilty to justice.

At the heart of an outcry in Bolivia has been a letter from the Paris-based organization Reporters Without Borders to President Quiroga in which its general secretary, Robert Ménard called for the identification and punishment of those responsible for Encina's murder and an investigation that demonstrates respe4ct for freedom of the press.

There was no crossfire in Catavi, according to Colonel Luis Caballero, chief of the Judicial Technical Police (PTJ) in El Alto. Nor was there an telephone call to alert his men, before 10:00 a.m., to the Encinas' serious condition.

"Encinas is believed to have gone to accompany his wife," he said. "He had recently taken a course with us on criminal investigation and as far as I know he had not been threatened. The theory about the clash has been who possesses the hillside for exploitation of the limestone deposits there. Both sides knew they were going to confront each other that morning."

Taking an undue risk

On the palm of the right hand of Eugenio Limachi Mamani, one of the people arrested, police found evidence that he had fired a gun. But, according to Caballero, anyone who wants to kill someone else aims at the head or the heart, not to the stomach as happened to Encinas, nor to the arm as occurred with Juan Mario Ticona Limachi.

Encinas has three daughters - Betty Pamela, 19; Cinthia Gabriela, 17, and Carla Angelina, 8. His brother-in-law René says that there was going to be a meeting of the Cooperative that day. "He had always followed the conflict closely," he said. "He was living in La Paz but my parents and my sister are from Catavi. I assure you that the two Air Force sergeants were there and we defended ourselves as best we could - with slings, hurling rocks, as they were shooting at us."

Air Force Colonel Maldonado is indignant. "Sergeants Limachi Ticona and Quispe Limachi have not been given any citation by the police nor the court," he said. "That day, one of them was in Santa Cruz and the other was playing soccer in El Alto. Do you believe that a television station is going to cover a clash between peasants at 6:00 or 7:00 on a Sunday morning? Nevertheless, the Air Force has no intention of covering up things of this kind. If any of its members is involved, it must respond. But that does not appear to be the case until and unless shown otherwise. We cannot go on the basis of speculation by news media, including international news agencies. We have not even been asked about it. You are the first to do so."

There is no record of the incident in Encinas' camera or tape recorder, now in the possession of his family. At Canal 24 television, for which he worked as a stringer, the news of his death fell like a bomb - with Linares, the production chief, he had been organizing a folklore festival.

It was even more of a shock in Catavi. "They are not from here," said Gregorio Mamani. "They are hired by other people with steady jobs, like at a paper mill or Coca-Cola, and they get their regular wages and Christmas bonuses while we get our living only from limestone."

He looks forlornly at the hillside, from whose summit two watchmen reported on their cellular phones at around 3:00 in the morning that tragic Sunday that buses were coming. It was a signal to the residents, gathered in the town square, to get ready to stop their homes being raided. "Juan Carlos [Encinas] was at the head of the column with his little camera and tape-recorder," Manuel Quiñajo Mamani said.

The attackers knew Encinas, according to local residents. With his camera and tape-recorder he was a thorn in their side. He took an undue risk by walking at the front of the column in defense of the people, if it is true as they say he did, even though what he was carrying was hardly lethal. Or perhaps it was in fact more lethal than any bullets from one side or rocks from the other.

|